I’ve long been fascinated by Soviet era Eastern European versions of Western film posters. Rather than using the original poster designs they feature new designs and illustrations, which are sometimes quite abstract and/or at times somewhat unsettling and sometimes contain just a hint or vague allusion to the content and atmosphere of the film.

I’m not sure why they didn’t use the original designs and I’ve deliberately not looked it up or read about it, preferring to just let my mind wonder (and wander) about them. Was it for rights or cost reasons? Was it an ideological issue? Would the Western posters be considered a form of invasive propaganda?

Whatever the reasons, the Eastern European poster’s designs seem to accidentally create some kind of phantasmagoric parallel world history of cinema.

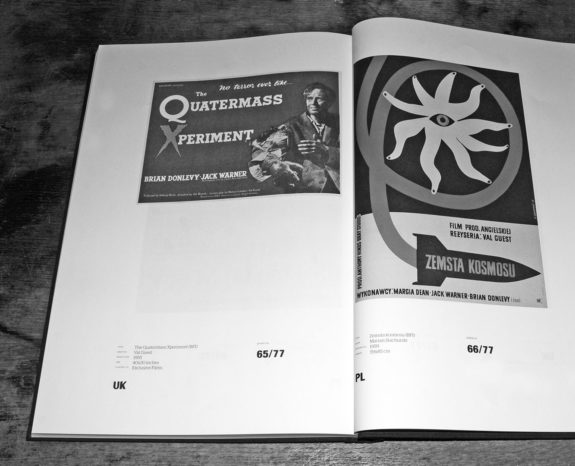

There have been a few books about / that feature them and the one the book images in this post are drawn from is called 77 Posters / 77 Plakatow, which was published in 2010 by Fundaca Twarda Sztuka with the support of the Polish Film Institute and the British Film Institute and accompanied an exhibition at the BFI.

In the majority of page spreads an original British poster design is shown on the left page and its Polish equivalent is on the right, which very effectively illustrates and allows for a comparison of their differences. Above is one of the original British poster designs and the minimalist illustrated Polish film poster for Nigel Kneale’s The Quatermass Xperiment which are featured in the book.

77 Posters / 77 Plakatow was released in a handsomely produced large format hard back edition with a textured cloth screen printed cover and is a hand numbered limited edition of just 300 copies. It’s not cheap but then I can imagine it cost a fair bit per copy to produce, especially in such a relatively short run.

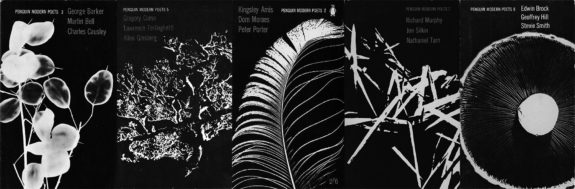

In a number of posters in the book there’s a stark minimalist and sometimes otherworldly, hypnagogic or dreamlike quality that, along with the likes of The Modern Poets books published by Penguin in the 1960s and 1970s, seem like a notable forebear or influence of some of hauntology orientated design, in particular that by Julian House of Ghost Box Records. House has mentioned that Eastern European film posters are a reference point for his work and a number of his Ghost Box Records designs have a similar use of stark monochrome and duotone pastoral images as is found in The Modern Poets covers, which is often combined in his work with imagery, atmosphere and design that invokes a subtly parallel world or cultural dreamscape – a sense of which Ghost Box Records in a wider sense often explores, creates and/or invokes.

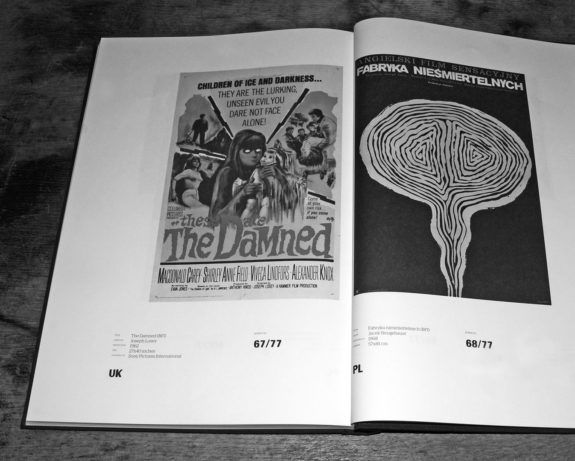

Above is the poster for Joseph Losey’s 1962 youth hoodlums and Cold War paranoia film The Damned. In this case the original British poster has a lurid, nightmarish pulp and exploitation quality to it, while the Polish poster reduces the film to a simple… maze? Cross section of a brain?

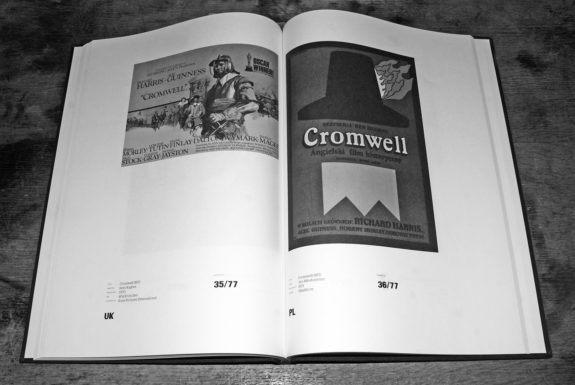

The Polish poster for Ken Hughes’ 1970 film Cromwell distills the film and the English Civil War to is core components; an upside down (deposed?) Royal crown and a Cromwellian hat in flames that may well be intended to represent the conflict and overturning of existing power structures at the time.

The above Polish poster for Don’t Look Now is, well, quite frankly just disturbing and it expresses the atmosphere and story of the film in a somewhat surreal nightmarish fever dream manner.

Both the British and Polish posters are also snapshots of previous decades when film poster design was often more illustration based and free in terms of design, having not yet been reduced to the contemporary state of affairs where they seem to generally be largely an exercise in contract fulfilment in terms of putting photographs of the actors front and centre and using recognisable stars as marketable branding tools. That has led to a lot of official contemporary film posters being either comprised largely of the title with photographs of the stars in an American football style line-up and/or their floating heads.

(This narrowing of design parameters and freedom in contemporary film posters may well have been one of the things which has led to the creation of a film related side industry of often illustrated third-party designed and released posters which in part hark back to earlier film poster design experimentation and freedom, such as though released by Mondo and which are featured in the documentary 24×36: A Movie About Movie Posters, which focuses on the rise, fall and return of illustrated film posters.)

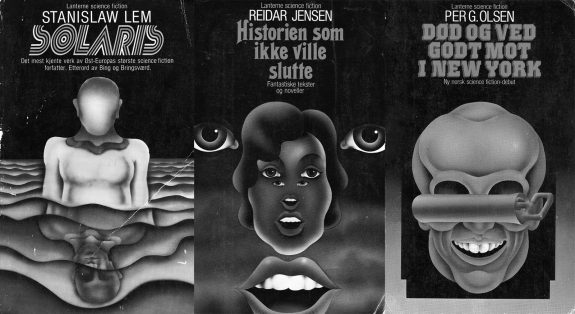

The Eastern European posters also bring to mind illustrated 1960s and 1970s Western science fiction novel covers, which I wrote about in A Year In The Country: Straying From The Pathways:

“In the 1960s and 70s, science fiction novel covers seemed to often allow space, or free rein for quite out-there slipstream-like illustration and design, including Peter Haars’ psychedelic illustrations for editions of books published by Lanterne in Norway which included those by local authors and the likes of Stanislaw Lem, Ursula K. Le Guin, Brian W. Aldiss, C.S. Lewis and Kurt Vonnegut. Viewed today such covers seem to encompass a sense of a kind of parallel-to-the parallel-world of a hauntological record label, and a point in time when the likes of ‘speculative fiction’ magazine New Worlds and Michael Moorcock’s Jerry Cornelius captured and expressed a moment where science fiction and related writing was hiply and exploratively psych like.”

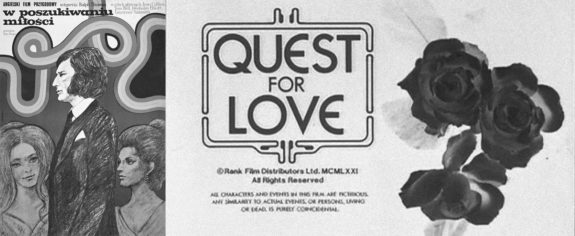

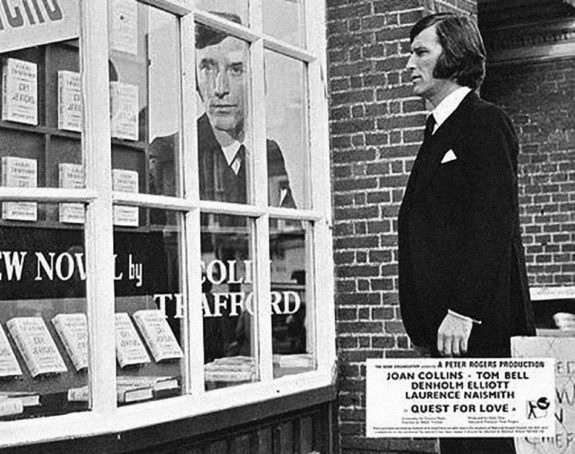

And talking of parallel worlds, above left is the Polish poster for the 1971 film Quest for Love. The poster design is almost, well sort of, quite straightforward design wise. It has a notable hand drawn quality but the illustration of Tom Bell is quite recognisable as him and seems to be based on a still from the film which was used in a Western lobby card (see below), although Joan Collins and Juliet Harmer, apart from their hairstyles, are less so (and Joan Collins has become Jean Collins in the lettering).

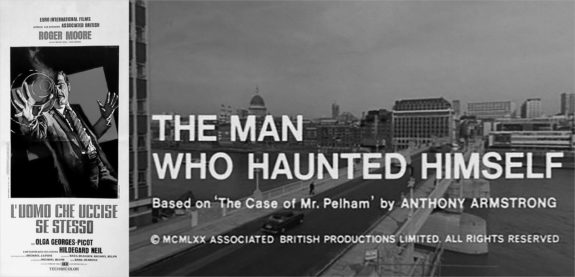

The film is something of a favourite around these parts and I often tend to connect it with The Man Who Haunted Himself (1970). Both films were released around a similar time and feature parallel world’s and/or lives, alongside showing an affluent, stylish upper middle class urban British way and strata of life that seems notably to contrast with much of later 1970s British cinema which often seemed to depict British life in a more gritty, downbeat manner. Joan Collins in particular in Quest for Love is strikingly stylish, all flowing couture-style fashion and grand structured hairstyles.

Perhaps in part the two films represent a transitional point when 1960s affluence and optimism began to give way to 1970s trouble and strife, along with being a snapshot of a related affluent and borderline aristocratic, at times formal or gentile establishment and high-end corporate way of life that seems to hark back to previous decades or even an earlier age.

Quest for Love is more overtly science fiction orientated than The Man Who Haunted Himself, which is, if not actually supernatural then at least preternatural and in terms of genre both could well be considered examples of speculative fiction.

Quest for Love involves a scientist who after an experiment goes wrong is thrown into a parallel world, where he is a successful fiction writer and the story has a strong romance element as he tries to prove to his wife that he has changed (which he has, very literally) and is no longer the unfaithful arrogant so-and-so he previously was. Eventually after he returns to his original reality he seeks out and saves the stranger who is the version of his wife in that world from a medical condition which doomed her in the parallel world.

In relation to its romance element and travelling to alternate realities it is not that dissimilar to 1980 film Somewhere in Time, which is a magic realist romance fantasy film in which a playwright wishes himself back in time to 1912 in order that he can find love with an actress he had seen in a photograph.

Quest for Love curiously doesn’t tell what happened to the version of himself in the parallel world which he has replaced; has his alternate self been destroyed by his arrival? Is he in some kind of limbo? Has he also been thrown into another world?

Some of those questions are more directly considered in The Man Who Haunted Himself, which could in part be considered a variation on the Jekyll and Hide story. In this film a married and successful high-end corporate executive called Harold Pelham briefly clinically dies after an operation and this causes an alternate version of himself to be released into the world, one who is his licentious alter ego and is far more ruthless in terms of his business decisions. The double begins to live his life in parallel to the original Harold’s, causing conflict and confusion for the original by having illicit love affairs, supporting a controversial financially beneficial but morally questionable business merger which the original Harold opposes and so on. It is not until considerably later in the film that the original Harold discovers the truth, by which time he has variously thought that there is a double masquerading as him or that he is going mad.

Eventually when the original Harold meets and confronts his ruthless double he is told by him that there is only room in the world for one of them. There is then a wonderfully psychedelically shot road chase and the new ruthless Harold drives the original off a bridge and to his death and is able to take over his life.

Viewed now the new duplicated Harold could be viewed almost as an accidental harbinger of a 1980s cinematic archetypal ruthless or amoral yuppie and personal financial gain orientated character for whom “the end justifies the means”.

Links:

- The 77 Posters / 77 Plakatow poster book

- The 77 Posters / 77 Plakatow site

- The Polish Poster Shop

- Network’s The Man Who Haunted Himself restored Blu-ray and DVD

- Quest For Love DVD (no Blu-ray on digital HD versions yet unfortunately)

- The 24 x 36: A Move About Movie Posters trailer

- The Ghost Box Records catalogue

Elsewhere at A Year In The Country:

- Peter Haars, New Worlds and the Slipstream of the Future’s Past

- The Modern Poets, otherly pastoralism and brief visits to flickering worlds…

- When Haro Met Sally, John Hughes, Stranger Things, Twins of Evil, Hauntology and Dark Seed – Parallel World Reimaginings and Phantasms