Leap in the Dark was a paranormal orientated British television anthology series broadcast on the BBC for four seasons in 1973, 1975, 1977 and 1980. There were 24 episodes in total, with the first series being documentary orientated, while seasons two and three mixed documentary footage with dramatisations of real-life cases of paranormal events. Season four featured original dramas themed around the paranormal and included episodes written by, amongst others, renowned writers Fay Weldon and Russell Hoban, alongside Alan Garner and David Rudkin, the latter two of whose work has since come to be associated with “wyrd” rural and folk or otherly pastoral culture.

At the time of writing only seven of the episodes were available to view online in degraded quality form via unofficial distribution. These include the first Pilot episode of season one, none of season two, two episodes of season three and four of season four. It is thought that all other episodes of season one were wiped and those of season two may also be lost. The British Film Institute’s National Archive, which catalogues and provides access to the BBC’s archival recordings, contains videocassette copies of all the episodes in season three and four. Some of these are not currently accessible by the general public as they are marked as “Status pending – Material requires inspection to determine preservation or access status”, which implies that it is not known if they are in viewable condition, or whether their condition may mean that they are too fragile to be played and viewed.

“To Kill a King”, written by Alan Garner, was the final episode of the fourth season of Leap in the Dark and if viewed with knowledge of Garner’s life it is a curiously self-reflective piece of work.

At the beginning of the episode nature, modernity and tradition are shown as being intimately intertwined in the drama’s location and a writer’s life, who is the central character; the opening shot is of a contemporary train rushing by, which segues into the bare trees of branches, that quickly come to foreground some form of large white radar-like dish, before the camera again moves to show a medieval style timber-framed house, which is the writer’s home.

The episode is set in and around this rural home where the writer lives a largely isolated life and shields himself from the outside world, and is suffering from a form of writer’s block and also possibly related mental distress and/or may have wider mental health issues.

There are only four characters seen onscreen: the writer, his agent, his sister and a spectral female presence which appears to be the writer’s elusive muse, and whose voice is only ever heard as a voiceover. Via this spectral muse lines of mystical verse come to the writer in the night, including the titular line “A night to kill a king is this”, but in the morning when he reads what he has written to his agent it is merely gobbledegook. The writer subsequently attempts to follow his spectral muse as she appears and moves through nearby fields, woods and a tunnel but she always remains aloof and elusive, and is apparently able to travel instantaneously across distances so that she is forever out of his reach.

The writer’s sister arrives unexpectedly and henpecks him about day-to-day matters (“Have a bath… the garden’s a mess” and so on) and when he, she and his agent eat together his mind seems to fracture. Following this the episode and the writer’s enclosed world come to resemble a less grand in scale version of Stanley Kubrick’s film The Shining, which was released in 1980, the same year that “To Kill a King” was first broadcast. In Kubrick’s film a writer, who is acting as a winter caretaker for an isolated snowbound hotel, and who has just two members of his immediate family for company, finds his mind fracturing in the enclosed world of the hotel; he endlessly types the same proverb on his typewriter and his sanity and world is invaded by hallucinatory preternatural or paranormal phenomena, presences and events. There are a number of similarities between this and Garner’s story: these include a writer who has lost their mental balance, the presence of just two other people closely connected to him, the unsettling use of a typewriter and also rhymes or proverbs, the sense of a fracturing mind and reality in the enclosed world of one building and the intrusion of spectral presences into that reality.

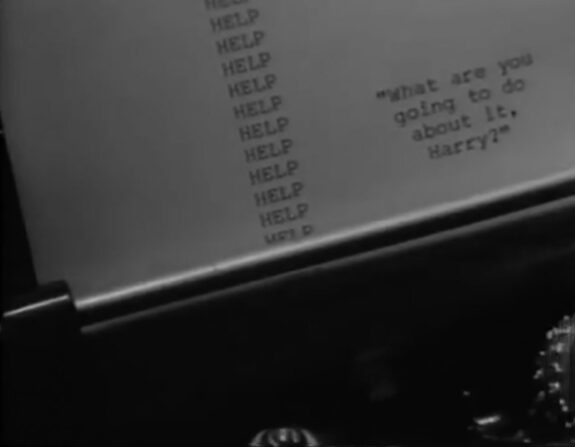

In “To Kill a King” as the writer’s mind and reality begin to fracture the phone rings and when he answers it his sister’s voice recites a child’s rhyme to him (“You are it…!”) Wandering off alone he sees an electric typewriter that begins to type on its own, typing that it could write and help before just repeating the word “help” coupled with a side note asking him what is he going to do about it, perhaps referring to his writer’s block, although this is unclear. Then a lump of coal which he earlier threw in frustration and anger into a pond appears in his hand, after which he becomes squashed against an invisible transparent surface as his mirror image is also trapped behind a television screen.

When this happens his sister and agent, who now seem to have become smugly taunting dopplegangers of themselves, appear and threaten to switch him off, shrinking him to a dot (as older cathode ray television’s images did when turned off) until he is nothing. In response to this he smashes the television screen and as he shouts in frustration the screen bleaches. There is a sense that he has reached his own personal lowest point and now has begun to recover, and he shaves and makes himself presentable, picks up notebooks, stokes the fire, sits and begins to recite the mystical verse he previously heard said by his spectral muse. His muse is then seen to enter the room and he begins to write again, after which the physical embodiment of his muse is no longer present, he is pictured alone and the episode ends with him focusing on his writing, apparently cured of his writer’s block.

“To Kill a King” appears to be deeply intertwined with Garner’s own life. The timber framed house is most probably actually Garner’s own home, who for a number of decades has lived in a Medieval timber framed home located next to Jodrell Bank radio observatory and the giant Lovell radio telescope, which is the radar-like dish shown in the drama. The house, as depicted in the episode, seems in some ways barely modernised; aside from it’s internal and external Medieval timber frame wall structure there is an open fire in the middle of a room with no obvious chimney and some of the lights are merely candles mounted on the walls.

Further connecting the episode with Garner’s life, he has written and spoken of how he was diagnosed in 1989 with manic depression, which he described as “the best news that I have ever heard” in The Voice that Thunders, a collection of his talks and seminars published in 1997, as it explained years of mania and inertia he had experienced. In an interview with Alison Flood titled “Alan Garner: a life in books”, which was published on theguardian.com on 17th August 2012, it is described how this included two years where for 12 hours per day he merely lay on the settee facing the wall, just waiting for the following 12 hours which he would spend in bed (and during which presumedly he was unable to write or find his “muse”). In the same interview he is also quoted as saying that he “went seemingly mad in less than three months” and sought psychotherapy following the adaptation of The Owl Service for television. With knowledge of such experiences in his life, “To Kill a King” seems very much like a form of creative autobiographical expression, perhaps a form of catharsis where he could explore and expel his own personal demons.

Although possibly merely an accident of the time of year when “To Kill a King” was filmed, the rural landscape in the episode seems to reflect the writer, and therefore also Garner’s at some points in his life, mental state; it is stark, even bleak, the trees are bare, the fields overcast and shrouded. As in David Rudkin’s “The Living Grave” episode of Leap in the Dark, nature’s vitality is further denuded by the degraded quality of the online video, as it both destaturates the imagery and also adds a murky cast to the rural scenes.

Adding to the autobiographical nature of the drama, the medal which the writer briefly looks at, before putting it away when his muse returns, is a Carnegie Medal. Only one of these are given per year as recognition for an outstanding new English language book for children or young adults, and in 1967 Garner was awarded one for The Owl Service.

Garner’s work has often been set in and around Alderley Edge, a village and rural area in the county of Cheshire in the UK:

“Garner grew up in Alderley Edge and can trace his ancestors there back over four centuries. As a child he played on the hill under which local legend says an army of knights sleep, guarded by a wizard until they are needed – a myth that became the basis for [The Weirdstone of Brisingamen – his first novel published in 1960].” (Quoted from “Alan Garner: a life in books”, as above.)

Garner says in the above article that his “background is deep and set in deep time, and in a narrow space, oral traditions going back a long, long time, which I inherited by osmosis”; in his work often it is as though he is attempting to add to this deep and narrow layering of stories and myth by setting it in the landscape he has lived amongst for many decades, while also attempting to ever more deeply embed and entwine himself with both that landscape and its myths.

As part of this layering his fiction and the real world at times quite explicitly entwine. For example aside from the appearance of the Lowell Telescope at Jodrell Bank in “To Kill a King”, in 2012 he published Boneland, the third novel in the “Weirdstone” trilogy, which tells the story of an astrophysicist who works at Jodrell bank, who is searching for his sister in the stars. Then in 2015 there was a series of lectures at Jodrell Bank named after him called The Garner Lectures, which explored the way science interacts with culture, the first of which was given by Garner himself (and that he said would be his last public appearance). As part of the promotion of the event, at the Jodrell Bank website a previously unpublished poem by Garner called House by Jodrell was posted, which both in its title and opening lines of “Across the field astronomers… Name stars. Trains pass” directly connects with both his home’s location and the opening and setting of “To Kill a King”. The episode is also connected with, revisited and returned to in the poem’s final line – “And a night to kill a king is this night” – which is from the mystical verse imparted by the writer’s spectral muse during the drama.

Returning again to both the character of the writer and the possible exploration and expression of Garner’s experiences with mental health issues in “To Kill a King”, the lines in the abovementioned mystical verse can also be seen to explore a related sense of isolation and effectively being removed from the world:

“I see not and I am not seen… Where twilight and the black night move together… in the four cornered castle… In the garth of glass…”

The use of the fairly obscure word “garth” could be seen as being an expression of such isolation, as it can variously be used to refer to a cloister, i.e. an area within a monastery or convent which only the religious are allowed to enter, a place or state of seclusion or to mean being secluded from the world as if in a cloister.

Although at points “To Kill a King”, as with much of the final series of Leap in the Dark, is not always easy viewing, even at times being harrowing, its final scene of the writer once again writing and seemingly having refound his muse and equilibrium, is something of an uplifting and hopeful ending for the series. However, it also has to be said there is still a certain stark unsettling air to the way that, after the image of him fades away, the only sound heard is the fast-paced scratching of his pen on the paper and it is difficult to know if this is an indication of a writer who is satisfyingly absorbed in his work after having rediscovering his muse or an indicator of him being caught up in a whirlwind of manic creation (which is something Garner has publicly discussed experiencing). The slightly unsettling air is accidentally added to due to the video of the episode which can be viewed online continuing to run after the programme has ended and an announcer saying “On BBC One now the late film is Touch of Evil” (!)

Elsewhere:

Elsewhere at A Year In The Country:

- Filming The Owl Service; Tomato Soap and Lonely Stones

- Robin Redbreast, The Ash Tree, Sky, The Changes, Penda’s Fen, Red Shift and The Owl Service – Wanderings Through Spectral Television Landscapes

- The intro to The Owl Service

- The Owl Service: fashion plates and (another) peek behind the curtain

- A wander around Red Shift, layers of history, the miasma / amber of cultural replications and associated reinterpretations / utilitarianisms

- Memories of midnight dreams and other nocturnal flightways and pathways

- She Wants to be Flowers – Filming The Owl Service (Revisiting)