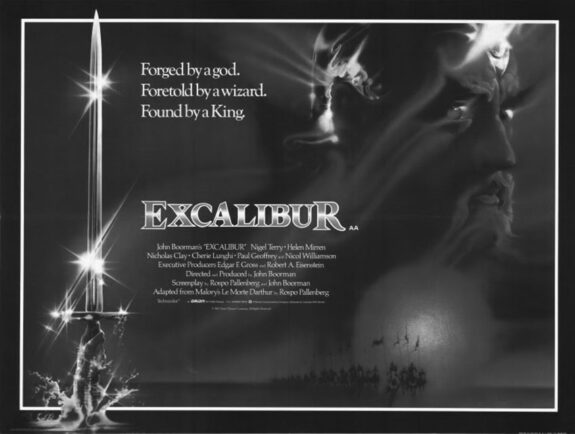

The John Boorman directed film Excalibur (1981) draws from Arthurian myth and legend, taking in its complete story cycle from the conception of the “once and future” King Arthur until his death (or slumber across the ages).

King Arthur is said to have been a British leader who lead the defence of Britain against Saxon invaders in the late 5th and early 6th centuries. The stories that are associated with Arthur are mainly drawn from folklore and literary invention, with modern historians debating and disputing these and also Arthur’s existence. Excalibur includes iconic and archetypal stories and characters connected with Arthur such as the wizard Merlin, Arthur pulling the mystical sword Excalibur from a stone, the forming of The Knights of the Round table and their quest for the Grail and the love triangle between the king, his wife Guinevere and his greatest knight Lancelot. Boorman co-wrote the screenplay with Rospo Pallenberg and it is based in part on Le Morte d’Arthur, written by Thomas Mallory and first published in 1485, which reworked existing stories and folklore about King Arthur and has since become one of the best known works of Arthurian literature.

Excalibur is far removed from being a straightforward mainstream piece of cinema, despite having had an at the time relatively high budget of approximately £30 million, if adjusted for inflation, being the number one film during its opening weekend in the United States and listed at 18th in the 1981 US box office takings.

Excalibur also forbears and stands apart from the trend for more purely escapist swords and sorcery and fantasy films in the 1980s, being nearer to an arthouse film cloaked in the trappings of blockbuster spectacle. It is a uniquely distinctive take on Arthurian myth that is unflinchingly full of sweat, stench, mud, blood, lust and primal desires but is far from being a realist, gritty or conventional depiction of King Arthur’s story:

[On its release] the film was a hit, but its reputation feels more cult-like, perhaps thanks to Boorman’s commitment to creating [its] otherworldly, mythic reality: it’s strange, lavish, and dream-like.” (Quoted from “A dream to some, a nightmare to others: sex, magic and myth on the set of Excalibur”, Tom Fordy, telegraph.co.uk, 18th Feb 2019.)

Mainly taking place in forest, castle and rural landscape and waterside locations, Excalibur is set in an unnamed British isles and what is described as the Dark Ages, and creates a form of Medieval never-never land that incorporates elements from around the 6th to 12th centuries.

Throughout the story there is a sense that Arthur’s reign is becoming a myth even while he is still alive and he says at one point “I was not born to live a man’s life but to be the stuff of future memory.” Alongside this, and underlying the entire story, is a warning of the doom that lies in wait when mankind, or an individual, loses touch with nature, or breaks natural laws and cycles, as was the cause of Arthur’s enfeeblement. Related to this, as discussed by John Boorman in his first autobiography, the film can be seen as a metaphor for the stages of mankind’s development:

“[While developing Excalibur] I began to formulate the idea that the Grail cycle was a metaphor for the past, present and future of humanity. In the early chapters, the Uther Pendragon period, man is emerging. He still has an unconscious magical connection with nature, both its violence and its harmony. That could be said to represent the deep past. [Merlin’s summoning of Excalibur from the lake focuses] the chaotic unconscious that lie beneath the surface. [After Uther abuses Excalibur’s power, violence and anarchy reign and so Merlin arranges that the sword passes to Uther’s son, Arthur] and its power allows him to impose his rule and make peace. As law and order are imposed, Arthur gradually forfeits his connection with nature. Camelot is established, a place of learning and science and order. Man becomes the master of the world. He pillages the earth. He cuts down the sacred forest. He loses his way… [Which] feels like our present. What of the future? What was once profusion becomes a wasteland. The King is sick from a wound that will not heal. The only way to cure the King and save the land is to find the Grail, the feminine symbol of wholeness and harmony, to find again a oneness with nature.” (Quoted from Adventures of a Suburban Boy, John Boorman, 2003.)

While in Excalibur Arthur builds the gleaming silver Camelot with good intentions, as suggested in the above quote, its construction has a potentially darker portentous flipside. It is the cause and expression of Arthur’s detachment from nature and the land and it could possibly also be seen as an attempt to tame not just nature but also an early stage in clearing away more problematic, less easily governable woodland etc settlements and their beliefs in the old nature based gods. Alongside which, when viewed today, Morgana’s use of magic to defy the natural process of ageing, and the way this brings about her demise, seems like a prescient comment on a contemporary expression of breaking natural cycles, that of plastic surgery and related attempts to prevent (but actually merely semi-hide or obscure) the physical signs of ageing.

Similar, at times Arthurian, themes of the corrupting effects of trying to break the cycle of ageing and problematic issues around creating a “civilised” elite haven which sequesters its inhabitants from the natural world are explored in Boorman’s dystopian science fiction film Zardoz (1974). In that an elite, who live in an impenetrable dome that separates and protects them from the wastelands and suffering in the wider world, have broken the cycle of nature through the scientific attaining of immortality and everlasting youth. However due to this immortality they have become effete and the men impotent, and their lives are filled with an overprivileged ennui, which sometimes finds a literal physical expression in that some of their number fall into a permanent catatonic state. They and their world are eventually destroyed by one of the enforcers the elite relies on to control and exploit the resources of the wastelands, who infiltrates the dome and brings about their destruction. The birth of this enforcer has similarities with the transgressive creation of Arthur and Morgana’s illegitimate son Mordred and him therefore being a bringer of destruction due to his birth breaking natural laws; the enforcer was genetically engineered through a selective breeding process by one of the elite, in order that he would bring about the destruction of their enclosed world and end mankind’s stagnation.

Although Boorman continued to make films after Excalibur, there is a sense in the 2013 documentary Behind the Sword in the Stone (aka Excalibur: Behind the Movie) that after making this film he felt that his work in general was done having, as is said in the documentary’s introduction, turned “a legend into a light for all to see”:

“It had been a lifelong ambition of mine to make this film, and when I saw [the final scene’s] shot of Arthur in the ship going out into the horizon, I felt that I’d completed my work.” (Quoted from Behind the Sword in the Stone, as above)

As with Zardoz, a number of Boorman’s other films have contained elements of, or that have parallels with, Arthurian legend and questing, the mythology of which he has been drawn to since an early age:

“Boorman, as he often mentions in interviews, has been gripped by myth and legend from early childhood, and mythic elements have found their way into virtually all his films… [many of his films prior to Excalibur] are premonitions, or half-submerged echoes, of the central myth that has obsessed him: the cycle of Arthurian legends… that he finally brought to the screen in Excalibur.” (Quoted from “Gone to Earth”, Philip Kemp, Sight and Sound, January 2001.)

Read today the above article on Excalibur is an early gathering together and linking of a number of the themes, films, television dramas etc which have become part of, and points of reference for, contemporary wyrd rural or otherly pastoral and folk horror orientated culture. To a degree the article presages, by almost a decade, the growth of interest in such culture that began to gather pace from approximately 2010 onwards, and through its discussion of related work it places Excalibur in a loosely interconnected lineage of post-war British mythic rural orientated cinema and television:

“In the 1940s and 50s the lush romanticism of such films as Canterbury Tale and Gone to Earth, [were] rooted in loving depictions of rural landscapes and a deeply felt quasi-pagan notion of Englishness… Nigel Kneale explored the interface between folk-myth and science fiction in his Quatermass cycle, as did (mainly for television) the playwright David Rudkin, whose Penda’s Fen… combines visions of such legendary figures as King Penda, the last pagan ruler of England, with a quasi-mystical view of the English landscape… Robin Hardy’s The Wicker Man… gleefully pitted puritanism against paganism in the Scottish isles…” (Quoted from “Gone to Earth”, as above.)

The article comments on how Excalibur is something of an exception in “the realism-obsessed canon of British cinema” in its exploration of the “kind of myth and legend “that have haunted the British imagination in both art and literature for generations”but that “it tends to be left to children’s movies… to put us back in touch with the magical”. Similar could be said for children or young adult orientated British television, particularly in the decade or so that preceded Excalibur’s production, when, for example, Arthurian related myth and magic was more likely to be explored in the likes of the young adult television drama series such as The Changes (1975), Raven (1977), Moon Stallion (1978) and some episodes of the anthology series Shadows (1975-1978), rather than adult orientated dramas.

As with Excalibur, these are productions which seem to stand aside from an almost stereotypical British reserve and embarrassment in the country’s national adult orientated cinema and television, particularly in less genre orientated work, in relation to magical and mythical themes. That such young adult orientated television drama from previous decades as that listed above, and its often surprisingly left of centre and multilayered mystical themes, has become of cultural interest to adults drawn to wyrd rural, hauntological etc culture is perhaps, in part, a reflection of adult orientated television work often not providing all that much space in which mythical and magical themes are explored, or if they are, it is often in a fairly conventional or genre friendly manner. This may also be one of the factors which explain the ongoing and growing interest in the likes of The Wicker Man (1973) and its decidedly adult, heavily layered and research underpinned exploration of mythical folklore.

Boorman has spoken of how he did not set out to create an historically accurate tale but rather intended to set Excalibur in a more imaginary world:

“If there was ever an Arthur… he’s sited in about the sixth century. But the date is the least important thing really. I think of the story, the history, as a myth. The film has to do with mythical truth, not historical truth… So [when making the film] the first trap to avoid is to start worrying about when or whether Arthur existed… [I set] it in a world, a period, of the imagination… trying to suggest a kind of Middle Earth, in Tolkien terms. It’s a contiguous world; it’s like ours but different.” (Quoted from “Excalibur: John Boorman – In Interview”, as above.)

In the above interview, and as also quoted earlier, Boorman says Excalibur’s story is about “man taking over the world on his own terms for the first time”. It is set on the cusp of when the old ways, magic, nature based belief systems, druids etc were receding, when Christianity became dominant and mankind becomes ever more reliant on technology. As Merlin says in the film:

“The days of our kind [i.e. wizards] are numbered. The one God comes to drive out the many gods. The spirit of wood and stream grows silent. It’s the way of things. Yes. It’s a time for men and their ways.”

Bearing this in mind, when famine and pestilence ravage the land in Excalibur it may seem slightly unexpected that it is not to agricultural etc techniques and technology that Arthur turns (although admittedly these would not have been all that advanced in the periods the film draws from) but rather he sends his Knights on a quest for the Grail. However, there is a sense at the end of the film, when he is mortally wounded and undertakes his mystical sea journey, that this quest was the last “hurrah” and reliance on magic, and his departure marks the completion of a changeover into the new ways and beliefs.

At the beginning of this post I described how Excalibur was commercially successful but far removedfrom conventional mainstream blockbuster cinema and had an otherworldly quality. Part of this is its use of mythical and magical themes and tropes but also due to its visual character, which, as also referred to earlier, give it a lavish, unreal, dreamlike quality:

“Excalibur still looks incredible – all sparkling emerald greens and shimmering silver armour. The Excalibur sword itself glows… Boorman and his cinematographer Alex Thomson achieved the effect with green filters over the lighting and even shone [green] lights onto moss to give the film ‘a kind of luminosity… so it felt like a myth rather than a reality,’ Boorman [says in documentary] Excalibur: Behind the Movie. ‘That’s what we were consciously trying to achieve, a kind of mystery magical feeling about it that it was another world.’ (Quoted from “A dream to some, a nightmare to others: sex, magic and myth on the set of Excalibur”, as above.)

As also commented on by Boorman in Excalibur: Behind the Movie, the unreal nature created by the extensive use of coloured lighting was added to by the on location weather during the film’s shoot; it rained almost every day of filming and this meant that there was constant moisture in the air, which refracted the light and gave it a kind of softness. The resulting imagery in the film often creates a sense that you are viewing events through the subtle haze of a dream.

Accompanying these light related characteristics, there is an almost magical sense of the passing of time. At one point Morgana kisses her young son and as their heads part you see that a decade or so has passed and Mordred is now a young man; when Uther thrusts Excalibur into the stone and dies the film cuts straight to the same scene but almost two decades later, the season has changed from winter to spring and the trees have their leaves, and as the camera pans it reveals that a settlement has sprung up around the sword and stone.

Related to the sense of Excalibur creating and exploring an unreal and mystical world, is the previously discussed way in which the film stands apart from the tendency towards realism in adult orientated British cinema through its exploration of myth and magic. Connected to this, the film also stands at a remove from much of British cinema in the abovementioned use of non-realist lighting, the ambitious nature of its costume and set design and the general epic scale of the film and its story. In relation to some aspects of this, its creation of a mythical, dream-like world in the British landscape shares some similarities with Powell and Pressburger’s film Gone to Earth (1950), which was referred to in a previous quote about a loosely interconnected mythic rural strand in British cinema and television:

“[Gone to Earth] has a Wizard of Oz-esque, Hollywood coating of beauty, glamour and quiet surreality which in part is created by the vibrant, rich colours of the Technicolor film process that it shares with that 1939 film… Often cinematic views of the British landscape are quite realist, possibly dour or even bleak in terms of atmosphere and their visual appearance and so Gone to Earth with its high end Hollywood razzle-dazzle which is contained in its imagery is a precious breath of fresh air.” (Quoted from A Year In The Country: Wandering Through Spectral Fields.)

There is a further intertwining of Gone to Earth and Excalibur in their depiction of worlds where the old ways, beliefs and magic still exist but are being removed from view by new beliefs etc, as Gone to Earth centres around a free spirited young woman who is still very much steeped in older rural ways of life and folkloric spells and charms.

The epic scale and sense of a heightened or imaginary reality in Excalibur’s story and the world it creates is added to by the film’s use of music. The soundtrack includes

multiple instances of composer Richard Wagner’s often highly dramatic music, whose vast four opera Ring cycle, written from 1848-1874, Boorman says in his Adventures of a Suburban Boy biography that he went to see as part of his preparations for making Excalibur:

“[The Ring cycle’s] Germanic myth has many elements in common with the Grail legend. Wagner’s music… inspired my writing and eventually insinuated its way into the movie.” (Quoted from Adventures of a Suburban Boy, as above.)

The soundtrack also includes Carl Orff’s distinctive and both ominous and darkly uplifting choral work “O Fortuna” from his cantata Carmina Burana, which he composed in 1935-1936. This particular piece is based on a collection of 24 medieval poems, and in a possibly serendipitous manner with Excalibur’s story, the lyrics are a complaint about Fortuna, the goddess of fortune and personification of luck in Roman and Greek mythology, and the inexorable fate that rules both gods and mortals.

“O Fortuna” was first used in cinema on Excalibur’s soundtrack and has since gone on to be widely known after being used in dozen’s of films, television programmes, video games etc, alongside being extensively sampled. In Excalibur it rousingly soundtrack’s the revitalised Arthur and his Knights on horse back as they ride over Camelot’s drawbridge and then through a surreally heavily white blossomed corridor of trees on the way towards Arthur’s final battle with his son Mordred’s army.

Elsewhere:

- Excalibur HMV Blu-ray Premium Collection edition

- Excalibur trailer

- “O Fortuna” sequence in Excalibur

- Excalibur memorabilia that you’ll need to break open a fair few piggy banks for at the Prop Store…

- Further Excalibur memorabilia at the London Film Museum

Elsewhere at A Year In The Country:

- John Boorman, Excalibur And Celluloid Myths / Realism

- Zardoz, Phase IV and Beyond the Black Rainbow – Seeking the Future in Secret Rooms from the Past and Psychedelic Cinematic Corners

- Zardoz, Space 1999 And Psychedelic Strands In 1970s Science Fiction

- Zardoz Ephemera / A Revisiting Of Fading Vessellings

- Zardoz and ways out of the maze

- Zardoz… in this secret room from the past, I seek the future…

- The Changes / The Disruption – Notes on a Flipside of the Pastoral Conversation

- The Changes, Threads, the bad wires and the ghosts of transmissions

- Gone to Earth / The Wild Heart, the Haunted Region of Wild Wales and a Sidestep into Talking Pictures TV’s Broadcasts of the Overlooked, Shadowed Archives of Cinema and Television

- Harps in Heaven, curious exoticisms, pathways and flickerings back through the days and years…

- Gone To Earth – “What A Queen Of Fools You Be”, Something Of A Return Wandering And A Landscape Set Free

- Mary Webb’s Gone to Earth and Forebears of the Layers Beneath the Land

- Gone to Earth – Earlier Traces of an Otherly Albion

- Zardoz, Gone to Earth, The Owl Service, The Village of the Damned, The Prisoner, Quatermass, The Wicker Man, The Touchables, Sapphire and Steel, The Nightmare Man, Phase IV and The Tomorrow People – A Gathering of a Cathode Ray Library and Rounding the Circle

- Gone to Earth and The Wild Heart – Revisiting Stories from the Haunted Region of Wild Wales