It’s a curious and intriguing thing the current interest in, flowering and harvesting of the “eerie” in the landscape, a kind of hauntological landscapism – or to semi-quote myself, expressions and explorations of an “otherly pastoralism”, a literal wandering through spectral fields.

In his article in the Guardian “The Eeriness of the English Countryside” (a section of which I recently quoted in a post on Texte und Töne’s publication The Disruption, which focuses on the 1975 television series The Changes and its anti-pastoral territory”) writer and academic Robert Macfarlane proposes that such interest and cultural expression is:

“…an attempt to account for the turbulence of England in the era of late capitalism. The supernatural and paranormal have always been means of figuring powers that cannot otherwise find visible expression. Contemporary anxieties and dissents are here being reassembled and re-presented as spectres, shadows or monsters: our noun monster, indeed, shares an etymology with our verb to demonstrate, meaning to show or reveal (with a largely lost sense of omen or portent).”

Such more overtly political explanations of the rise of such culture may well be one of the reasons for the rise in interest and activity in such areas and it could be linked to a related hauntological sense of a yearning or mourning for lost progressive futures.

However, although I say overt, it is often anything but overtly political; rather as Robert Macfarlane states, these “anxieties and dissents” are being reassembled as spectres in the landscape – contemporary bogey men or vague feelings of dread on the edges of consciousness.

As I discuss in the A Year In The Country: Wandering Through Spectral Fields book, for myself part of the need for related exploring comes from a sense of the cultural landscape having now been thoroughly harvested and colonised. Once shadowy undisturbed cultural niches, nooks, crannies and overlooked corners are now routinely explored and displayed for all to see, often both within their own niches and also via more mainstream channels.

I have nothing against the mainstream per se. It is more just that if you are drawn to those overlooked corners of culture in the sense of being both an explorer and somebody who at times appreciates the less well harvested then there is hopefully a little more space for such things at the moment in the “otherly pastoral / hauntological landscapism” than within traditional pop/urban orientated fringe culture.

This cultural landscape may create a space for cultural pursuits and interests which are not so focused on youth; anecdotally and based on the first hand referencing of culture from 1960s-1980s (i.e. by those that experienced it in their own youth, rather than as an interest in work from a time prior to your own birth) that can often be found within such work it could be surmised that much of the audience for it is now quite far from the hurly burly of the first flush of youth.

An interconnected viewpoint on the reasons for the current interest in the confluence of wyrd folk, otherly pastoralism, hauntology etc could be that it is part of the creation of an imagined parallel world or plane of existence – one which variously allows for a break from the above mentioned “contemporary anxieties and dissents” or just because humans as a species seem to possibly uniquely be fascinated by and have a need to tell stories, spin yarns and create waking dreamscapes.

Accompanying which historically cities and urban areas have often been seen as the primary and main cultural incubators which while it may to a degree may still be true, the increasing costs of living in cities in the UK may also mean that only those from certain social and economic groups are more able to have the time to required sit on and incubate their cultural ideas, scenes etc until they are able to fully hatch. That time requires a certain and not inconsiderable access to monetary wealth and/or a youthful ability and energy to live in what may be trying circumstances.

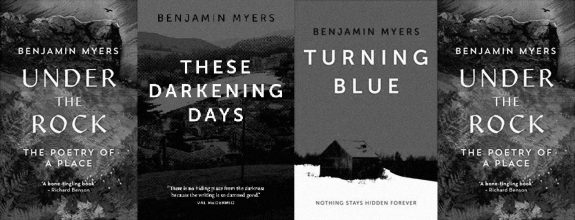

Such considerations are eloquently and evocatively discussed in writer Benjamin Myers’ non-fiction book Under the Rock: The Poetry of a Place (as an aside his fictional work in recent years has been called rural or Dales noir and explores interconnected territory to the above sense of otherly or hidden undercurrents in the landscape):

“We leave London early one June morning, Della and I. It is a decade ago and all our combined possessions have been crammed into a removal van that left the night before. What remains is shoved into the back of my car…

We hit the morning traffic and an hour later are still edging along Vauxhall Bridge Road into Victoria. Our mood is strained, conversation terse. The stress of a house move is underpinned by the knowledge that once you leave the city it is very difficult to return; one only moves to London when either young or wealthy, and now we were neither.

Twelve years earlier… I had tracked a similar journey in reverse, driving a borrowed car full of clothes, books, records and treacle down from the north-east of England to find myself circling Piccadilly Circus at five o’clock on a Saturday evening, Eros looking down at me as I attempted a U-turn much to the chagrin of the dozen black cabs caught in my slipstream…

Eventually I edged my way south of the river over the same bridge I crossed now, to move into a dilapidated transpontine squat in a labyrinthine Victorian building… Here I lived rent-free for four years.

But now it was the height of a recession and London was no city in which to be poor. Where once it was a dizzying maze to be navigated one day at a time, a playground for constant reinvention, now it was a place owned by the property developers, the oligarchs. The old one-bedroomed flat, with its bath on breeze blocks in the kitchen and infestation of mice, abandoned by the local council for thirty years, had recently sold for £800,000.”

Perhaps the sometimes cheaper living costs of rural areas, accompanied by the relatively low entry points for digital technology and virtual rents for online territories (the new-ish nooks and crannies?) are combining to become some of the spaces that allow more easily for the aforementioned cultural incubation.

Elsewhere:

- The Eeriness of the English Countryside article at The Guardian

- Robert Macfarlane’s The Old Ways: A Journey on Foot

- Ben Myers’ website

- Under the Rock: The Poetry of a Place

Elsewhere at A Year In The Country:

- The Changes / The Disruption – Notes on a Flipside of the Pastoral Conversation – Part 1: Wanderings 1/52 (And the Start of a New Yearly Cycle)

- Electric Eden – Unearthing Britain’s Visionary Music – Folk Vs Pop, Less Harvested Cultural Landscapes and Acts of Enclosure, Old and New: Chapter 1 Book Images

- Day #190/365: Electric Eden Ether Reprise (#2): Acts Of Enclosure, the utopian impulse and why folk music and culture?