The Prisoner television series (1967-1968) involves a secret agent who resigns and is than abducted and incarcerated in an isolated village, given the denomination No. 6 and repeatedly battles with his superiors who attempt to find out why he resigned and it has become one of the ultimate and most iconic of all cult television programmes.

Much of the series was filmed in Portmeirion, which is a tourist village in North Wales designed and built by Sir Clough Williams-Ellis between 1925 and 1975 in the style of an Italian village. In some ways the whole of Portmeirion could be seen as almost being a folly on a grand scale (although it is used extensively by visiters, holidaymakers, festival goers and Prisoner devotees) and it has a grandly envisioned and unique, borderline surreal ornate character.

I first became aware of The Prisoner in the mid-1980s when it was re-broadcast by Channel 4 on British television and it was probably one of my early exposures to cult film and television; I am not sure that I fully understood it at the time but I found myself very drawn to and fascinated by it.

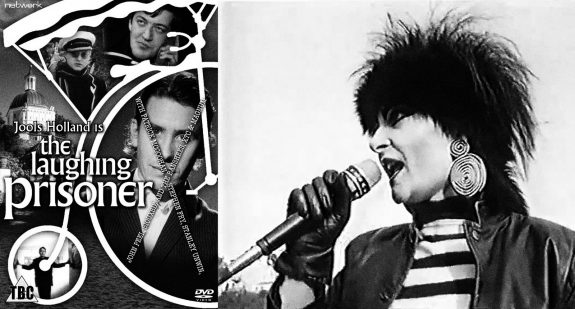

When I first saw the series it was on a small black and white television set, while I think the first time I saw sections of it and Portmeirion in colour was in a 1987 episode of the Channel 4 music programme The Tube called The Laughing Prisoner, which was a “Prisoner” special filmed in Portmeirion. This was based around a premise which mirrored The Prisoner series in that one of The Tube’s presenters resigns from Channel 4 and is also abducted into The Village and the show featured clips from The Prisoner alongside music performances by Magnum, XTC and Siouxsie and the Banshees.

Probably because of the above way in which I first saw The Prisoner, although I subsequently saw the series in full and colour, when many years later I visited Portmeirion in part it seemed initially as though I was visiting the set of The Laughing Prisoner as much as the actual series.

In a way it was something of a shock to actually be there in reality; part of my mind still expected Portmeirion to be a mirage of the imagination. Also the fully fleshed-out reality of the place and that it consisted of fully functional buildings etc was a little unexpected – it made me think of author William Gibson saying about when he first visited the set of the film based on his short story Johnny Mnemonic (1981) and how he has spoken about that he did not expect it to be realised in such high-resolution (i.e. attention to convincing detail etc). In a way part of me expected Portmeirion to be just set like facades that could easily be tilted over, as some of the characters prove to be in the Western set episode of The Prisoner “Living in Harmony”.

At one point during my visit I wandered through the forest-like area next to the main village and eventually came upon a near deserted estuary beach bordered by cliffs, a place of great and striking beauty. Looking back in some ways this felt like the most Prisoner-esque section of Portmeirion and conjured visions of No. 6 desperately and repeatedly attempting to flee and escape The Village’s confines via the beach before being captured by Rover (an entity from the series depicted as a large floating white balloon which would be summoned to chase down those where trying to escape).

The Prisoner was co-created (or possibly solely created, according to some views) and also partly written and directed by its star Patrick McGoohan, Prior to this he had been the star of more conventional secret agent series called Danger Man (1960-1968), which to a degree The Prisoner could be seen as a more left-field continuation of.

The non-conventional nature of The Prisoner and in particular the final episode is said to have caused some confusion and even anger amongst its audiences. However, watched today some of the episodes appear to be reasonably conventional albeit cleverly and twisting-turningly plotted dramas; although it is difficult to know if this is because the series proved somewhat influential and future programmes have taken on board elements of the series and also it is not easy for the viewer to place themselves in the mindset of the 1960’s audience encountering it for the first time and who were expecting more conventional television fare.

By the end of the series, particularly the penultimate and final episodes, named Once Upon a Time and Fall Out respectively, The Prisoner has wandered far off well-worn and expected tracks and another of its core themes – the conformity of the individual and subservience of their needs to society’s – are very much highlighted.

Once Upon a Time continues one of the core themes of the series; the authorities employing a wide array of complex, layered and at times scientifically advanced techniques in order to get information out of No. 6 about why he resigned. They seem to not want to “damage” him by using more conventional heavy-handed interrogation techniques, although the mental stress some of their repeated efforts may have put him under could well have psychically damaged anybody without nerves of steel. By this episode they seem to have finally lost patience and No. 6’s interrogator, No. 2 – one of a series of people all with the same denomination tasked with getting information from No. 6 – asks to undertake a dangerous technique called “Degree Absolute”, which will involve a battle of wills literally to the death.

In this episode No. 6 is put into a trance state that causes his mind to regress back to childhood. He is then taken to the underground “Embryo Room” where the episode largely takes place, which is depicted as a largely blank black enclosed and dreamlike space filled only with various often childhood orientated props and a fake living room and kitchen.

No. 2 lectures and derides No. 6 about his non-conformist tendencies:

“Society is a place where people exist together”, “Yes sir”, “That is civilisation”, “Yes sir”, “The lone wolf belongs to the wilderness”, “Yes sir”, “You must not grow up to be a lone wolf”, “No sir”, “You must conform”, “Yes sir”, “It is my sworn duty to see that you do conform.”, “Yes sir”.

In the final episode the authorities’ comments on non-conformity seem to mirror some similar real-world views of later 1960s youth rebellion:

“Youth… it may wear flowers in its hair, bells on its toes… but when the common good is threatened, when the function of society is endangered, such revolts must cease. They are non-productive and must be abolished.”

This is also connected with No. 6 and others’ behaviour:

“We have just witnessed two forms of rebellion. The first uncoordinated youth rebelling against nothing it can define. The second an established, successful, secure member of the establishment, living upon and biting the hand that feeds him… Well, these attitudes are dangerous. They contribute nothing to our culture and are to be stamped out.”

The final episode was written and directed by Patrick McGoohan and according to some sources needed to be written in just a few days after the series was prematurely cancelled. Whatever the truth of this, there is a sense of “What the heck, we might as well just go for it and do what we like” about the episode and it does not provide a conventional ending with loose ends tied up – if anything it creates more than existed before…

To be continued in Part 2 (which, depending on when you are reading this, may not yet be online)…

Elsewhere:

- The Prisoner opening sequence

- The Prisoner at 50 / trailer

- Portmeirion

- The Prisoner: 50th Anniversary Edition