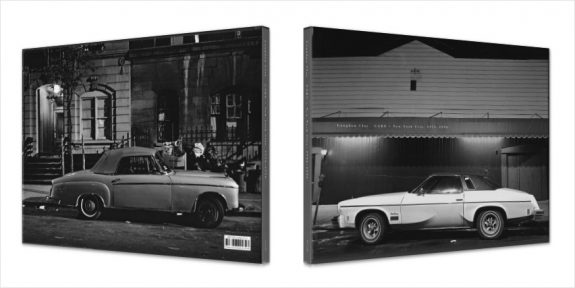

At first glance the photography book Cars: New York City, 1974-1976 by Langdon Clay, published in 2016 by Steidl, can seem like something of a cuckoo in the often pastoral nest of A Year In The Country

However parallel stands could be connected between it, European hauntology and lost spectres of the past…

This book focuses exclusively on nighttime photographs of parked cars, in the city and period mentioned in the title.

Looking through the book it is as though the population of the world has disappeared, leaving only these automobiles and as the book progresses the viewer can find themselves beginning to question if the cars are merely vehicles/vessels for transport or are they living entities themselves – they instill a sense of being ghosts, both sentient and yet not.

However these are not the friendly, anthropomorphised “Cars” of Pixar fame.

Eerie is a word that has been used in connection with the photographs and that would seem appropriate – there is something subtly disquieting about these brooding, alone, nighttime inhabitants.

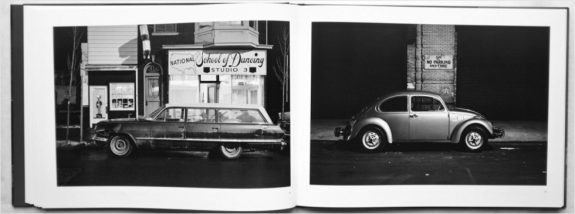

There are very few people in the whole book and where they appear they are not captured in sharp detail: they appear as a blurred figure in a diner which stands alone and apart from the city and could be from both the 1950s and/or the 1970s.

While in another photograph the faceless person pictured in a car, although probably the result of late night lighting conditions and a related long film exposure, here seems to edge towards a sense of being trapped, a form of possession, horror films etc.

There are occasionally signs of human habitation and activity – here and there lights are on in businesses and bars but rarely can anybody be seen inside nor entering or leaving and in a small number of photographs the lights of passing cars have been reduced to vapour like trails but these are few and far between.

Accompanying which and returning the “eerie” atmosphere of the photographs, these images of empty streets in a teeming, heavily populated city induce a subtle sense of unease or dread, in a not dissimilar way to that in which John Carpenter has often used empty streets in his films, which although in the middle of densely built urban spaces seem to be isolated and alone.

(And they possibly also connect to John Carpenter’s adaptation of Stephen King’s novel Christine and its central character which is a possessed, supernatural late 1950s American car.)

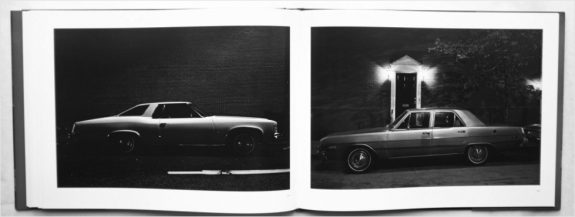

Although book is page after page purely of stationery cars at night, it does not impart a sense of repetition. Rather the endlessly changing or sometimes almost morphing from one to another character of the cars and the small details in the backgrounds of the photographs keep the viewer entranced – the changing businesses that stand behind where the cars are parked, the fallout shelter sign next to a meat company and its inspection certificate and so forth.

(It is surprising just how ubiquitous fallout shelters appear to be in these photographs, with them reappearing a number of times, in a manner which viewed today seems both surreal and a potent reminder of the threat of destruction which populations then lived under.)

Most of the cars in the photographs are “civilians” – cars for personal use – but one image features a police car which as a symbol of power/authority seems to be something of an interloper in amongst what is otherwise the empty frontier like nighttime city depicted in the book.

One factor which decidedly separates the photographs and the cars in the book from today is the capturing of signs of rust, advanced wear etc – something which you rarely seem to see today in cars.

The non-American made cars – the recurring Volkswagen Beatles etc – also seem like interlopers amongst what are often muscle car-esque and post-populuxe American vehicles.

(The phase muscle car is generally used to refer to often two-doored American sports cars that feature powerful engines and which are designed for high performance driving. They generally have an aesthetic which is quite distinct and separate from European sports cars.)

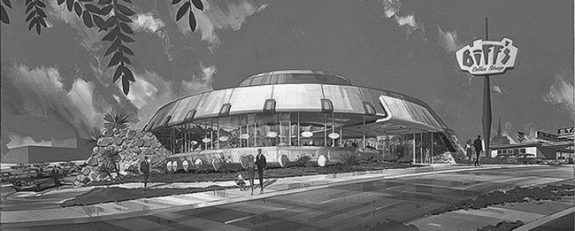

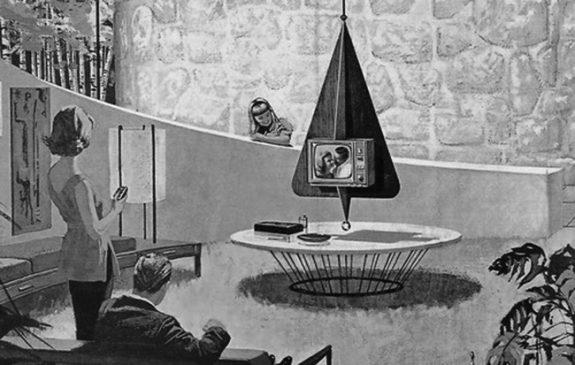

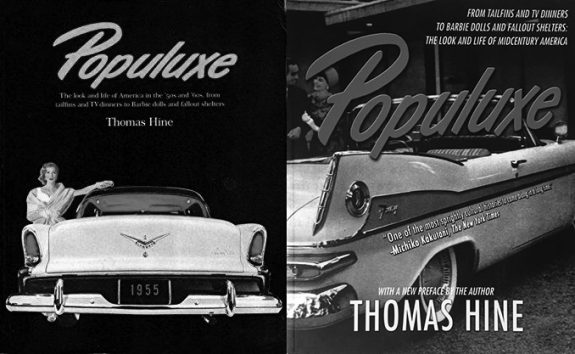

Populuxe was a consumer culture and aesthetic in the United States popular in the 1950s and 1960s – the term comes from a combination of popular and luxury. It is associated with consumerism and overlaps with mid-century modern architecture, Streamline Moderne, Googie architecture and other futuristic and Space Age influenced design aesthetics that were optimistic in nature, futurist and technology focused.

(Two editions of Thomas Hine’s book on populuxe style and culture.)

Viewed now such design can look like a vision of the future’s past – a more consumer and market lead, colourful and seemingly joyous American version of British progressive modernism and various related post-war state lead attempts at “building a better future” that included new towns, high rise flats and other brutalist architecture.

Often the style/aesthetic of the cars pictured in Langdon Clay’s book seem to hark back to that earlier 1950s-1960s era in America; a time of expanding power and influence on the world stage, optimism and excess production capacity (delineated by automobile’s extravagant design and physical size) but in this context – late at night, alone, empty, battered, worn and with temporary often rough repairs – they seem to imply a sense of a society and/or nation that was tired, weary, past a peak.

To be continued in Part 2…

Elsewhere:

Cars: New York City, 1974-1976 Langdon Clay’s own site

Sample pages of Cars at Joseph Chadleck’s photograph book site

And at Steidl

The Vault of the Atomic Space Age

Thomas Hine, author of the book Populuxe

Elsewhere at A Year In The Country:

1) Week #22/52: Fractures Signals #1; Flickerings From Days Of Darkness

2) Fractures – Night and Dawn Editions Released

3) Week #24/52: Fractures Signals #3; A Dybukk’s Dozen Gathering (/Looping?) From Around These Parts

4) Ether Signposts #42/52a: Matthew Lyons and a Populuxe Mid-Century Modern Parallel World

5) Wanderings #48/52a: A Few Ether Gatherings… Ghost Signs, The Vault of the Atomic Space Age and Avantgardens

6) Chapter 7 Book Images: 1973 – A Time of Schism and a Dybbuk’s Dozen of Fractures