There is a mini film sub-genre of pastoral fantasy, with at times elements of folk horror, wherein late 1960s and turn of the decade high fashion mixes with grown up fairytale high jinks, wayward behaviour and sometimes a step or two or more towards the dark side, all carried out in dreamlike isolation in the woods and pastoral settings.

The three main films aligned with such things are Queens of Evil aka Le Regine or Il Delitto del Diavolo (1970), Tam Lin aka The Devil’s Widow (1970) and in a more loosely connected manner The Touchables (1968).

All three of these films draw from, to varying degrees, some of the often-defining themes of folk horror: being set in rural places and buildings where activities and rituals can develop or take place without easy escape to or influence from the outside world, normality and societal norms.

In all three films there is more than a touch of Hansel and Gretelisms about the way their victims (the word is used loosely here as it is not always clear cut how willing at various points they are in their own capture) are treated and kept in these remote country or woodland settings; pampered yes but also possibly fattened for the pot.

Transgression is a word that comes to mind when describing them and despite its initial more escapist, fairytale and dreamlike cabin in the wood setting, visuals and story, Queens of Evil becomes a very transgressive, unsettling film as it progresses.

The film was featured on BBC Radio 4’s Film Programme (2004-2021), which although it could take trips into some of the outer reaches of film, the appearance of Queens of Evil on it was something of a surprise as this high fashion, woodland folkloric critique of power and psychedelic idealism belongs to notably more outlying areas of cult filmdom.

Its plot follows a handsome young freewheeling hippie idealist who comes across a house in the woods after he has been involved in a road accident where a materially wealthy gent was killed. Living in this house are three young women who take him in, charm, nurture, seduce and confuse him. Everything is rosy for a while but there is something off-kilter about the setup and he cannot quite seem to leave.

It is an at points chimeric fantasy which is largely set in sharply stylish but indolent, tree-inhabited period interiors and is full of late 1960s ethereal high-fashion along the lines of Ossie Clark and Celia Birtwell’s work from then and also incorporating the period folkloric-meets-psychedelia imagery collecting of the Psychedelic Folkloristic Tumblr page1 and its reflection of a relatively brief point in time around the later 1960s to early 1970s when fashionability turned towards folk and pastoral concerns.

In terms of other reference points it creates a sense of a gently decadent grown-ups version of a tea-party in the woods, a dash of Snow White (at one point somebody says “It’s just like Snow White’s house” about the cabin in the woods), a bit more of a dash of Hansel and Gretel and its tales of leading astray, more than a touch of the earlier mentioned and loosely interconnected kidnapping and pop-art pastoral playground film The Touchables, alongside the social critique and/or dreamlike qualities of some of Czech New Wave films such as Daisies (1966) and Valerie and her Week of Wonders (1970).

In fact, although Italian the spirit it conjures could well belong to that cycle of at times fairytale like Czech films as it has a similar playful, childlike idyll and sometimes-dreamlike quality to it but if you should go into the woods today, well, let us just say you may well be hiding behind the sofa by the end.

Tread carefully is sage advice. It is playful in parts but this is most definitely a film for grown-ups and not always an easy piece of celluloid to watch.

Pastoral giallo might be another appropriate genre title alongside folk horror as it was produced in Italy at a similar time as some films which have been connected with the giallo genre and as with a number of those Queens of Evil combines thriller, horror, mystery, supernatural and more visceral moments in a stylish and stylised manner.

It could well also be appropriate to include The Wicker Man (1973) as another reference point as in both films there is a similar sense of game playing, of leading a worldly innocent through a set of rituals and of differing levels of power and control in a rural setting. Also, in common with that towering relatively modern folklore tale, apples and symbols of temptation play a part in this game. And as with The Wicker Man, this is a tale full of its own and borrowed mythology, which seems to exist and be told in a world of its own imagining, where the outside rarely intrudes.

By the end you realise that this sometimes fairytale fable is actually a quite severe satire or critique on society, of those in higher echelons of power and also the decadence and potential corruptibility of the psychedelic/free love movement and its associated idealism.

In many ways it is a story of a culture tottering right on the edge of when the utopian, carefree, sun-drenched dream of the 1960s was about to fall into the darkness of its own dissolution in the following decade (Liege & Lief becomes Comus, to draw parallels with folk music’s progression at the time).

In terms of this loose mini sub-genre of pastoral fantasy, The Touchables is more rooted in the later part rather than the tipping point of that 1960s dream, although it does represent a world and culture which seems to have become untethered and possibly one which lacks a moral centre.

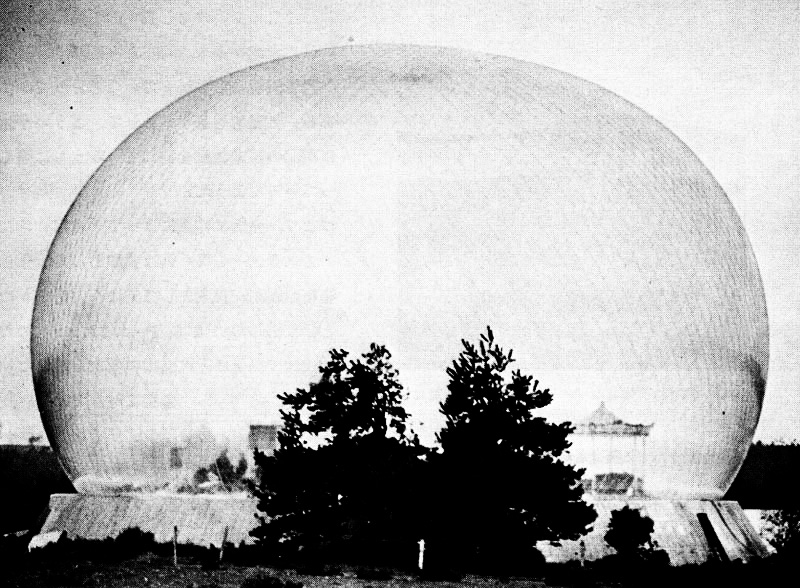

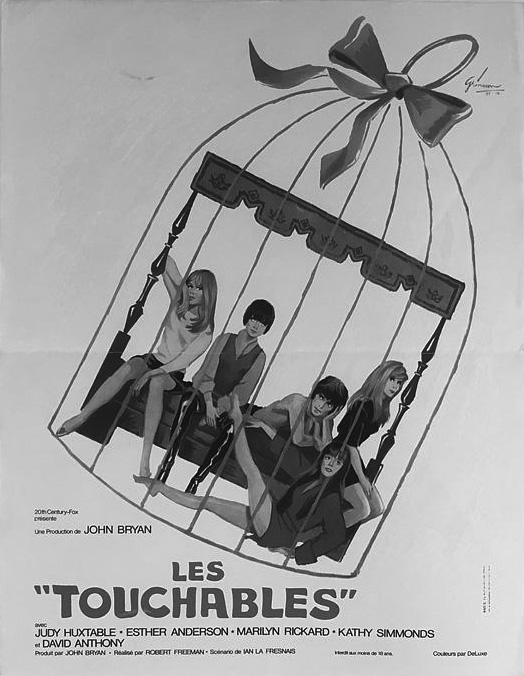

It is a very modish tale of a group of stylish sixties women who live in a huge see-through plastic bubble in the middle of the countryside and who kidnap a pop star as “a temporary solution to the leisure problem” in order make him their plaything. Mixed in with this are the stealing of a Michael Caine dummy, gangsters, wrestlers with rather refined aristocratic tastes, a fair bit of high fashion styling and a fine pop-psych title song by Nirvana (the 1960s band rather than the more high profile later Seattle based grunge rock group).

Essentially, at heart it is a caper romp but one that is at more than one remove from the mainstream and quite surreal in its setting and the mixture of elements it contains.

It is a film which in part evokes a sense of how did they get the money to make it, due to its left-of-centre nature. Well, maybe it was partly because it was made during a peak of interest in all things youth and “Swinging London”, at a point when money was quite possibly being thrown at anything that might make inroads into the pockets and pounds of a younger music and fashion- orientated demographic.

Also being directed by photographer and designer Robert Freeman, who worked extensively with The Beatles during 1963- 1966 including photographing and designing a number of their album covers, may possibly have helped add kudos and aided the practicalities of seeking funding.

The Touchables is a more a playfully, surreally adult pastorally- set fairytale or fantasy than the more overtly folk horror Queens of Evil (although it does have some quite shocking moments in amongst its escapist visual confections) but as mentioned earlier it mirrors some of the elements of that film; in both stylish late 1960s women kidnap a pretty boy to live in their own rural dreamlike domain.

It was not a surprise to discover that The Touchables was based on a script by Donald Cammell (with a screenplay by Ian La Frenais), as in part it represents a proto, more pop-art, possibly light hearted take on the film Performance (1970), which he wrote and co-directed. As with The Touchables, Performance also incorporates a theme of a popstar living in an enclosed bubble world, although its setting is in some ways more prosaic as it involves a former popstar who lives a reclusive, isolated life in a London flat rather than in a rurally set large-scale see-through plastic dome as is the case with The Touchables. Alongside this and as a further point of connection, both films also intertwine professional gangsters and related criminal activities within these secluded worlds.

One intriguing aspect of The Touchables is that there is not even an attempt to explain how the stylish group of female kidnappers’ bubble or lifestyle are afforded, nor why there seems to be no outside comment or interference by mainstream society, authority etc about their quite frankly rather unusual and very prominent giant blow-up see-through home that is sitting in the middle of the countryside, complete with jukebox, canopied merry go-round etc.

This aspect of non-explanation it shares with Queens of Evil, although in that film there is the possibility that its main characters’ lifestyle is afforded by those further up in a related hierarchy who wish them to carry out their manipulative intentions.

If ever a film seemed custom-made for a high-definition brush and scrub up restoration it would be The Touchables. The BFI’s Flipside strand could well be an appropriate home in that it has created a space for high end reclaiming and restoration of the more cult and forgotten side of cinema, which The Touchables would fit rather well amongst.

At the moment the version/s that are available are unofficially distributed and have a colour palette where the hues seem quite muted and, although it is difficult to tell from publicity photogr- aphs etc, there is the possibility that it was actually intended to be more a pop-art dazzle of colour, which would possibly suit the film more.

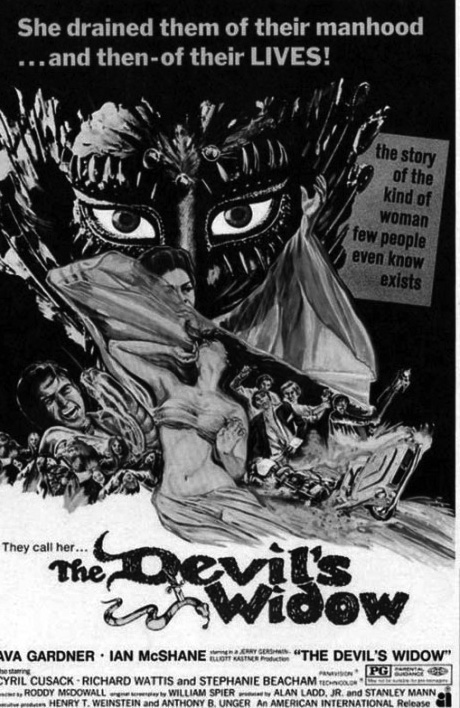

Which brings me to Tam Lin, that in contrast with The Touchables but as with Queens of Evil has been released on officially licensed high-definition Blu-ray editions. It’s a curious film that as with Queens of Evil and The Touchables does not easily fit into any particular mainstream genre; it is a loose modern adaptation of the traditional folkloric tale and song “The Ballad of Tam Lin”, relocated to the country home of an almost mythologically wealthy older woman which is peopled by various late 60s hipsters, hunks and prepossessing actresses of the time (including Madeline Smith, Joanna Lumley and Jenny Hanley) and soundtracked by British jazz-folk band Pentangle.

Hollywood legend Ava Gardner stars as the wealthy, older woman, alongside a dapper Ian McShane who plays a young man that catches Ava Gardner’s character’s eye and Stephanie Beacham as the innocent from the world outside.

It was directed by Roddy McDowell, who is possibly most famous for playing the lead simian character in a number of the Planet of the Apes films that were released from 1968 to 1973. This was the only time he directed which is a pity as this film shows that he had considerable promise in that area.

The plot involves the immensely rich older lady Michaela Cazaret, who gathers up hip young things to come and live, play with and amuse in her country mansion; her actions seem like a scooping up or pied piper-esque leading as she heads a convoy of cars through roads walled by pylons into her country lair. Cue childlike games (how can a game of frisbee seem so very odd?), partying, pleasing of the senses, imbibing and so forth.

As just mentioned, she has a particular soft spot for one young gent named Tom Lyn (Ian McShane), taking him into her bed and possibly her cold heart. However, he falls for an innocent from outside their bubble world – the vicar’s daughter played by Stephanie Beacham – and tries to escape from the clutches of Michaela, which displeases her somewhat and his life and freedom become rather fraught.

It was released in 1970, the same year as Queens of Evil, and along with that film it is also all high baroque dandyism and decadence turning towards something somewhat darker.

In Tam Lin there is a sense of playful opulence and a mod/ post-mod sharpness to the style which could be compared and contrasted with say the murk, grime and tattiness of the also sub/counter culture orientated and folk horror related undead biker film Psychomania which was released in 1973. They are separated by but a few years but are worlds apart in terms of the aesthetic style, societal/economic conditions, atmosphere and possibly optimism that they represent or portray.

As with Queens of Evil, Tam Lin is set at the very tipping point of a transitional, liminal period; a time where the psychedelic, hippy, free-living of the 1960s is about to turn inwards and curdle. Tam Lin seems to express the end of that point in history’s utopian dream more overtly or implicitly when one of the sacraments of that era, psychedelic substances, are used as a form of weapon, hounding and destruction and also when the freedom loving hipsters become a hunting mass-mind pack.

The main films focused on in this chapter all present bubble- like worlds, literally or otherwise but whereas in The Touchables and Queens of Evil there is not an obvious source of financial, practical sustenance for these ways of life, in Tam Lin it is commented that Michaela is:

“Immensely rich. She can afford to live in her dreams and she takes us into them for company.”

Although The Touchables is more rooted in the real-life fantasia of pop-art psychedelia, in Tam Lin and Queens of Evil there is a “Do they, or don’t they?” about the female protagonists’ possession or not of magical powers. Are they merely manipulative or something more preternatural?

In Tam Lin the young hipsters are referred to as “covens” in the credits and it seems almost that Michaela weaves a spell of possession around her playthings (and hence the pied-piper siren like gathering mentioned earlier).

Queens of Evil probably feels more overtly ethereal and unreal in this sense; Tam Lin seems quite rooted in the real world and is in some ways a more “normal” film but it is a world and celluloid story that is just askew in ways that are hard to quite put your finger on; the phrase “magic realism” would not be out of place.

This askew normality is one of the things that makes Tam Lin such a curious film and slice of culture; it is a heady mix of mainstream talent and decidedly both mainstream and non-mainstream filmmaking. This is heightened by the presence of a Hollywood goddess or legend in the main female role; Ava Gardner here has a form of innate star or otherly quality that makes her seem separate, above and beyond the mere humans which she surrounds herself with.

And they are terribly disposable, these young pretty things, they are there but at her bidding and can be sent away just as easily, with Michaela stating at one point:

“I want a party for all your special friends. I want a whole new world.”

Tam Lin was also made at a high-water mark of folk rock and the returning music refrain throughout the film is the traditional folk song “The Ballad of Tam Lin” from which the film takes its inspiration, performed in the film by Pentangle and which infuses and intermingles with the more conventional music score.

The film’s story follows that of its folk music forebear which with its fantastical tales underpins and layers the sense of this being an adult fairytale; in both the film and the song a young maiden (called Janet in the film and often also in the song) is drawn to a rake-ish rogue, nature takes its course and the ridding of the resulting child is narrowly averted.

However, the young man has been encaptured by a sort of queen (of wealth in one, of the fairies in the other) and he may well become a tithe or offering to differing hells (capricious whims in one, literal in the other). Upon his escape and his lover’s attempted rescue of him, he is turned into various beasts and even burning matter by his captors in order to make her leave him (via psychedelic ingestion in one, presumably magical powers in the other). His form of transport for his escape bears the same white colour in both, though one is powered by a combustion engine and the other is of a more equine nature.

And in the end in both the queens of fairies and of wealth are angered by but acknowledge their defeat and his escape.

However, the film does not leave the viewer with the sense that this particular queen had permanently stepped away from the fray and the young lovers’ lives; there is something genuinely unsettling and even subtly psychopathic or unhinged in the portrayal of Michaela’s need for control.

Once again returning to the sense of an ending of an era and of a dream, in some ways the innocent Janet played by Stephanie Beacham is a representative of the normal, decent world outside this coven-ish pack and its ways; reflecting this, in the film it is said that they are and must be treated as scum and they appear to represent a dissolute, amoral gathering that needs to be escaped from.