The film within a film in Berberian Sound Studio is only shown visually by the illustrated intro sequence, with the violence and excesses of the live action parts only being expressed and implied by the sound effects that are created within the studio setting, guidelines given to the studio engineers or Toby Jones’ character’s repulsion or surprise at them.

Although he demurs at the extreme nature of some of the sequences he is expected to work on, this appears to be only in a British rather polite way. Alongside which, his only connection with back home and a more morally grounded world are the letters from his mother which are initially descriptions of bucolia but which later become their own form of dark horror.

Accompanying which during the film the interior world of the studio is only left when the film breaks through into the British countryside, which provides a brief relief via greenery and daylight. This is in considerable contrast to the corridor, studio, bedroom and night-time courtyard where the remainder of the film is set.

As the film progresses, the nature of the work, the self- contained world of the studio and the manipulative coercion, persuasion, denial or recalcitrance of the other staff seem to combine to corrupt him and they weaken and eventually remove any resistance he has to the nature of the work.

By the end of the film and as a sense of the demarcations between reality and fiction erode Toby Jones’ character becomes as much a facilitator and collaborator in the imagined film’s excesses as those around him.

The themes, actions of the characters etc in Berberian Sound Studio could be seen as questioning the reasoning and motives behind the making of giallo and related horror film, its subsequent cult following and raising up as a form of artistic rather than possibly purely sensationalistic exploitation cinema.

If this is the case then it can be seen as a film which explores and debates viewers’ and makers’ complicit creation and enjoyment of such areas of film, ones which without that elevation could be considered in part to be curious and questionable forms of culture…

Peter Strickland’s films bring to mind those kind of arthouse, sometimes transgressive films that have often gone on to find a cult following but have not always become mainstream critically acceptable.

For example, films that would have once appeared in the pages of Films and Filming magazine which was published from 1954- 1990; often European cult arthouse independent cinema, with leftfield, exploratory and sometimes transgressive or salacious subject matter and presentation.

Both when discussing his own work and in writing by others, there have been numerous mentions of such earlier films which are said to have fed into his and also of a sense of homage that his work contains.

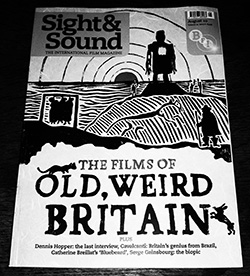

For example, the BFI’s Sight and Sound film magazine called The Duke of Burgundy a “phantasmagoric 70s Euro sex-horror pastiche” and as referred to previously the likes of prolific fringe film maker Jesús Franco are often referenced when writing about the film.

This sense of homage within Peter Strickland’s films can sometimes be quite overt; in his film The Duke of Burgundy the night time dreamlike sequence which sees the screen and one of the main characters consumed by a rapidly layering collage of lepidoptera seems to quite directly visually reference experimental film maker Stan Brakhage’s Mothlight film from 1963 in which layered natural elements and insects to create a rapidly moving montage.

The connections to and lineage of such films via degrees of homage in his work can provide an intriguing cultural layering, acting as pointers to other areas of exploration and on this topic, he has written the following:

“The inclusion of an obscure reference done in an obvious fashion can be precarious in terms of what that reveals about a director’s motivations. At worst, the act of homage is merely posing and diverting attention onto the director rather than the film, but when done organically and effectively, as with both Greenaway at his best and Tarantino, it enriches the film and places it within a wider (albeit self- imposed) lineage that can be rewarding for the curious viewer.” (Quoted from “Peter Strickland: 6 films that fed into The Duke of Burgundy”, bfi.org.uk, 13th February 2015.)

Such earlier films as Mothlight and those of a Scala-esque nature can be culturally and/or aesthetically interesting and intriguing, they may also possibly have a great poster or soundtrack but they are not necessarily always all that easy to sit through in terms of also being forms of entertainment.

However rather than homage, Peter Strickland’s films often seem to more be an evolution of them, taking previous work as some of its initial starting points but then recalibrating their themes, tropes and aesthetics to create work which alongside it containing layered cultural points of interest can also work as entrancing entertainment (albeit that may also at times be more than a little unsettling).