Part 2 of a set of posts which explore various aspects and offshoots of Brutalist architecture. (Visit Part 1 here.)

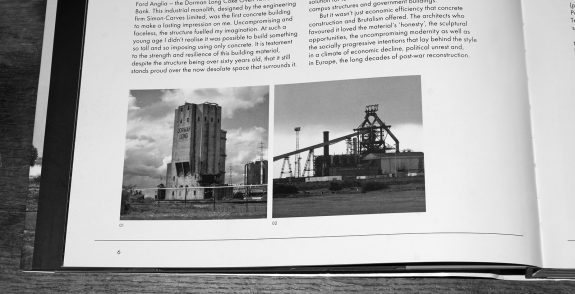

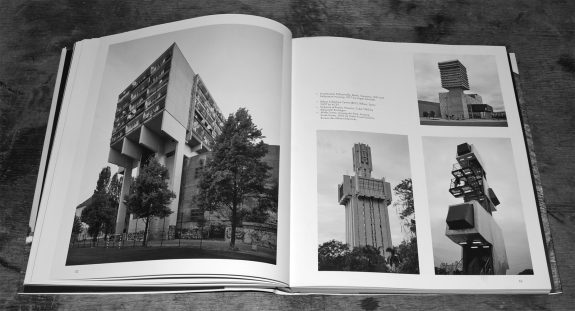

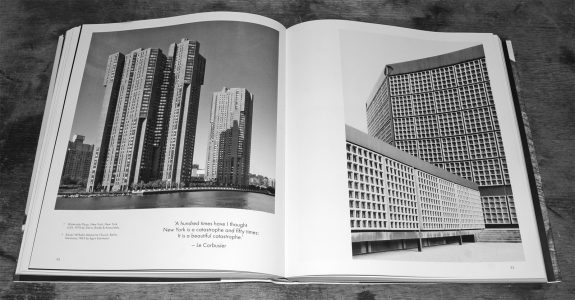

In Part 1 of this post I wrote about Peter Chadwick’s book This Brutal World, which is a collection of the photographs he has taken of Brutalist architecture.

As written about in the book’s introduction Peter Chadwick’s introduction to and passion for Brutalist architecture was initially inspired when at a young age he saw a concrete built “industrial monolith” blast furnace, which he says was the first concrete building that made a lasting impression on him. Also in his youth he would visit an ICI owned large-scale chemical plant in Wilton, an area in the North-East of England, of which he says:

“By night… it became a different world altogether, transforming itself into a shimmering, industrial flame-lit Las Vegas. This view inspired others, including film director Ridley Scott, also a native of the North-East, who based the flaring chimneys in the opening scenes of Blade Runner on the ICI plant in Wilton.”

In the opening scenes of that 1982 film the city skyline, its endless lights and plumes of flame are strikingly beautiful and modern when seen from above and at night but the reality of that particular future at ground level are considerably more layered, worn and challenging, intermingling elements of futurism with a harsh, unnatural urban way of life and crumbling design from the past.

That sense of a tarnished retro-futurism in relation to Brutalism is indirectly given expression in lyrics from Saint Etienne’s song “When I Was Seventeen” which are quoted in This Brutal World and which in a robotic voice namechecks a number of Brutalist orientated architects:

“Lubetkin, Corbussier, van der Rohe, Mendelssohn. Future, future, the future is clean and modern.”

In practice the future as expressed by Brutalist architecture did not always turn out to be quite as shiningly “clean” or bright as may have been intended.

Brutalist architecture is generally associated with concrete as a building material, which it could be suggested is a less natural, warm or human seeming building material than say bricks or stone. Although why that is the case is hard to quite fully define in the case of bricks vs concrete as both are created via “unnatural” manufacturing processes.

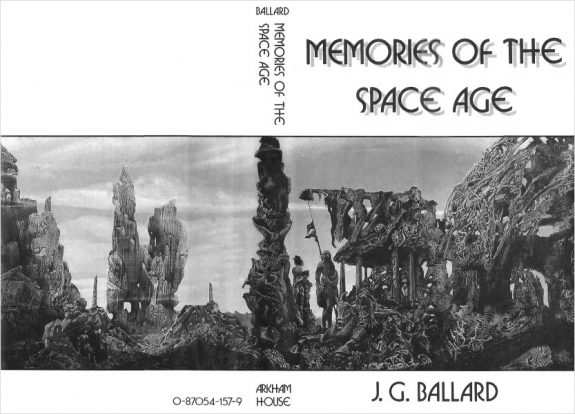

This aspect of the “unnatural” nature of Brutalist architecture is also heightened by the large-scale of many such structures, which often dwarf human inhabitants and the manner in which multi-storied Brutalist buildings often stacked their inhabitants on top of one another, taking some of them high above the earth. It also brings to mind author J.G. Ballard’s stance on space travel and his observations that essentially space is an unnatural place for us to be:

“Ballard’s melancholy… take is that humanity’s urge to enter the cosmos is an expression of an almost child-like hubris – which is bound to end badly!” Andrew Smith writing at Goodreads on J.G. Ballards book Memories of the Space Age (1988) – a collection of short stories set in a future when the space program has ceased and civilisation appears to be on the wane.

Related to this in contemporary times real world space exploration plans have been largely either curtailed or at least considerably scaled back in terms of ambition, which connects to Brutalist architecture as both forms of endeavour to a degree contained elements of futurism and when considered today both can invoke a certain sense of melancholia and lost imagined future pathways.

(This is a subject which was explored in the album The Quietened Cosmologists which was released by A Year In The Country in 2017 and which took as its theme: “…a reflection on space exploration projects that have been abandoned and/or that were never realised, of connected lost or imagined futures and dreams, the intrigue and sometimes melancholia of related derelict sites and technological remnants that lie scattered and forgotten.”)

As with space travel, due to the exploratory and large-scale nature of Brutalist architecture, related problems and disasters may also likely to be on a grand scale; which unfortunately more than once has proved to be the case.

The failures and catastrophes related to such buildings, particularly in relation to their use as social and/or state funded housing, may have been in part and at times due to a lack of correct maintenance or the political will to correct the social imbalance which often seemed to become part and parcel of say Brutalist housing estates but may also be partly a reflection of the sometimes over-reaching hubris which inspired them.

It is difficult to fully separate whether it is the intrinsic aspects of for example large-scale multi-storied architecture which cause such disfunction and/or that lack of correct maintenance and political will etc. As is often the case in many aspects of life it is probably a synthesis of these and other factors, although the close proximity of the inhabitants of such buildings also brings to mind laboratory experiments where rats live together relatively peaceably when given a reasonable amount of living space but begin to fight and enter into conflict when that space is reduced below a certain level.

In terms of such failures and catastrophes it could be as simple as philosopher and theorist Paul Virilio’s comments about sea ships:

“The invention of the ship was also the invention of the shipwreck.”

Prior to the creation of such large scale buildings related disasters on the scale and in the form they allow for were just not possible as, well, the buildings etc did not exist.

Another layered and multi-faceted aspect of large-scale Brutalist (and other) architecture relates to how it effects light and viewpoints within cities; it is thought that viewing the horizon for extended periods of time can release endorphins (naturally occurring “feel good” chemicals) in humans. This could be an argument for the “unnatural” state of living in densely populated cities, where the horizon is often obscured by buildings. Conversely the viewpoint from the higher floors of high-rise, taller scale buildings may enable the viewing of the horizon again – although equally obversely those lower down may have their view more obscured by the presence of other similar surrounding buildings.

Elsewhere:

- This Brutal World

- This Brutal World at Phaidon publishers

- Peter Chadwick’s This Brutal House site

- The Blade Runner intro sequence

- Blade Runner – 30th Anniversary Ultimate Collector’s Edition (one of the few ways still left to watch the version released in UK cinemas)

- Saint Etienne’s “When I Was Seventeen”

- Saint Etienne’s Words and Music album (featuring “When I Was Seventeen”)

Elsewhere at A Year In The Country:

- Reflections on Brutalism Part 1 – This Brutal World and a Study of The Shape of the Futures Past: Wanderings 14/52

- Peter Mitchell’s Memento Mori and Bugs in Utopia: Wanderings, Explorations and Signposts 35/52

- Artifact Report #40/52a: The Quietened Cosmologists – Released