Just recently published are the books Folk Horror Revival: Urban Wyrd – 1: Spirits of Time and Folk Horror Revival: Urban Wyrd – 2: Spirits of Place.

These two volumes are flipside companions to the other often more overtly rural and folk orientated Folk Horror Revival non-fiction books which contain work by multiple authors, with these new books focusing on the uncanny, unsettling and, as the titles suggest, the wyrd in urban settings. They take their initial inspiration from the urban wyrd concept and phrase created by author Adam Scovell, author of Folk Horror: Hours Dreadful and Things Strange, and describe urban wyrd as being:

“A sense of otherness within the narrative, experience or feeling concerning a densely human-constructed area or the inbetween spaces bordering the bucolic and the built-up or surrounding modern technology with regard to another energy at play or in control; be it supernatural spiritual, historical, nostalgic or psychological. Possibly sinister but always somehow unnerving or unnatural.” (Quoted from Spirits of Time.)

While in his Introduction to Spirits of Time Adam Scovell says:

“So, what essentially can be described as the Urban Wyrd ?… The Urban Wyrd is a form that taps into the undercurrent of the city. In a similar way to psychogeography, it can find new narratives hidden below the top-layer; of dark skulduggery and strangeness beyond the reasonable confines of what we consider part of city life.”

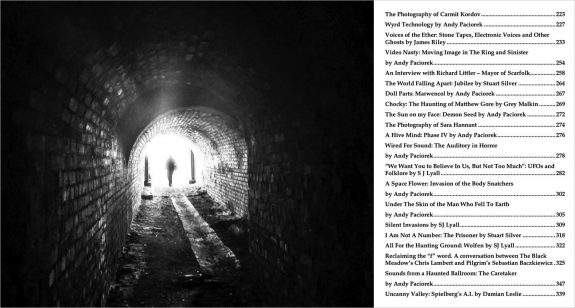

(Above left: image by Grey Malkin from Spirits of Time.)

(Above left: image by Grey Malkin from Spirits of Time.)

In a similar manner to hauntology or what is sometimes called wyrd folk, urban wyrd is not a strictly defined and delineated area of work or genre. In some ways it is more a loosely gathered common feeling, atmosphere or spirit. This sense of the looseness of what constitutes urban wyrd is acknowledged in Spirits of Time’s Foreword and also its Introduction, in which Adam Scovell describes urban wyrd as being more like a mode, i.e. nearer to a general sense of how something is expressed, rather than a genre or specifically defined category. It is connected in this sense to other loosely gathered grouped cultural areas including folk horror, hauntology, psychogeography etc and Spirit of Time contains a sense of caution with regards to narrowly overly defining such concepts:

“Folk Horror does not quite work like a genre and, therefore, should be considered a mode instead. There are many such modes with interlinking material – terms often bandied about such as Hauntology, Psychogeography et al. – that fit within some schemata of a mode. They have enough shared material to understand why they are discussed in the same breath but enough difference to accept that amalgamating everything under one descriptive banner homogenises material, undermines much of its thematic nuance and can be too general… Like all of these terms [Urban Wyrd] is just another context, another way of seeing material grouped together. It is not designed to dissect them and remove their dark hearts.” (Quoted from Spirit of Time’s Introduction.)

As discussed in the Introduction, urban wyrd, can be seen as a way of remythologising cities, as much of hauntology and folk horror does for sometimes interlinked subjects and/or types of areas. It can also be seen as an expression or attempt to add a hidden, not fully explained, sometimes near mystical layering to contemporary life and is in contrast to the modern-day prevalence of focusing on the rational, scientific, that which is fully explained and so on. Urban wyrd in part could be considered as a way of adding mystery and what was once known as magic to urban environments and in this way could also be thought of as being loosely connected to similar attempts and urges in past and current religion and spirituality.

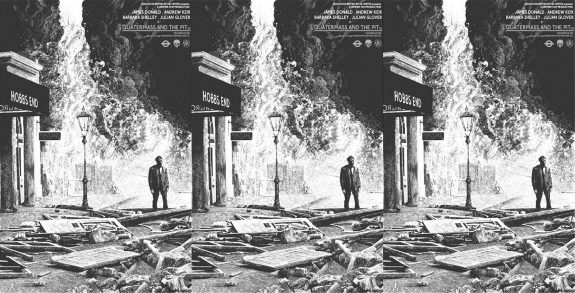

As with hauntology, work which could (loosely) be labelled urban wyrd often utilises known and recognisable locations but then adds a sense of the unnerving, unsettling, the uncanny to this. As Adam Scovell also says in his Introduction in reference to this and Quatermass and the Pit: “In the tunnel where you get the tube, there could be a devilish Martian craft under the brickwork”. An equivalent in folk horror, hauntology etc could be considered the beauty and nourishment provided by nature and rural landscapes, which become something much more unsettling in The Wicker Man; the pleasant rural village in The Midwich Cuckoos which becomes a site for an in some ways subtly enacted alien invasion; previous eras’ TV station idents becoming spectral totems which are imbued with an underlying “otherlyness” and so on.

These things all curiously interlink, which is something I discuss in the chapter “Spectral Echoes: Hauntology’s Recurring Themes and Unsettled Landscapes”, which I contributed to Spirits of Time:

“Hauntological orientated work is often, although again not exclusively, urban orientated and at times conjures a landscape where Brutalist architecture and post-war new towns become part of a parallel world hinterland of the imagination in which all is not quite what it seems and that can contain a subtly off-kilter dystopic or unsettled atmosphere. Although not obvious bedfellows it has also curiously come to share territory and intertwine with the further reaches of folk culture and what could be loosely called wyrd folk, an otherly pastoralism or eerie landscapism.

“On the surface such more rural flipside of folkloric and hauntological cultural forms are very disparate and yet both have come to explore and share similar landscapes. What may be one of the underlying linking points with both wyrd folk etc and hauntology is a yearning for lost utopias; in more otherly folkloric orientated culture this is possibly related to a yearning for lost Arcadian idylls, in hauntological culture it may be connected to a yearning for lost progressive post-war futures and a past that was never quite reached.

“Particular points of interconnection could be seen to be the sometimes focusing in related work on abandoned or decommissioned Cold War infrastructure including once secret bunkers and also electricity pylons and broadcast towers. Such bunkers etc. although often rural in location also often share a Brutalist architectural aesthetic with the likes of concrete built urban schools, government buildings, tower blocks etc. from previous decades.

“Despite their utilitarian day-to-day nature rural and urban located electricity pylons and broadcast towers in hauntological and otherly pastoral orientated work, as with abandoned bunkers and Brutalist architecture, have become symbols and signifiers of an eerily layered landscape.”

The two Folk Horror: Urban Wyrd books jointly contain nearly 1000 (!) pages and have literally dozens of chapters by also literally dozens of authors. Below is just a slight taster:

Quatermass and the Pit: Unearthing Archetypes at Hobb’s End by Grey Malkin

The Haunted Generation: An Interview with Bob Fischer

A Tandem Effect: Ghostwatch by Jim Moon

Voices of the Ether: Stone Tapes, Electronic Voices and Other Ghosts by James Riley

An Interview with Richard Littler – Mayor of Scarfolk.

“We Want You to Believe In Us, But Not Too Much”: UFOs and Folklore by S J Lyall

“This isn’t for Your Eyes” – The Watchers by Richard Hing

City in Aspic: Don’t Look Now by Andy Paciorek

Review: Concretism – For Concrete and Country by Chris Lambert

Phantoms and Thresholds of the Unreal City by John Coulthart

Iain Sinclair: Spirit Guide to the Urban Wyrd – Interviewed by John Pilgrim

The City That Was Not There: ‘Absent’ Cityscapes in Classic British Ghost Stories by Anastasia Lipinskaya

High Weirdness: A Day-trip to Hookland by Andy Paciorek

The Voice of Electronic Wonder: The Music of Urban Wyrd by Jim Peters

Find out more about the books via the links below…

Links:

- The Folk Horror Revival: Urban Wyrd books and other titles are available at Lulu

- “This is not a test…”: The Urban Wyrd books at the main Folk Horror Revival site

- The Urban Wyrd Twitter page

- The “Urban Wyrd” In Folk Horror – an article by Adam Scovell at his site Celluloid Wicker Man

Elsewhere at A Year In The Country: