The British TV drama Penda’s Fen, written by David Rudkin and directed by Alan Clarke, has become one of the more prominent touchstones for “wyrd related culture.

While Penda’s Fen is very multi-layered in terms of the themes and subjects it explores, it does at one point quite specifically focus on the exploitation and possible misuse of natural resources and landscapes when a character launches into a paranoid conspiracy-like rant:

“What is it, hidden beneath this shell of lovely earth? Some hideous angel of technocratic death? Some alternative city for government from beneath? Motorways there, offices, control suites. Silent there, empty, waiting for the day… those lonely places our technocrats chose for their extreme experiments… Sick laboratories built on or beneath these haunted sites…”

Which brings me to White Lady which was also written by David Rudkin (and he also directed it) which is much more overtly specifically concerned with ecological issues and on his website he describes it as being “A parable on the agro-chemical destruction of nature”.It was originally broadcast as part of the ScreenPlay drama anthology series in a primetime evening slot on BBC Two in 1987 and has not had an official home release on either physical media or digitally – although again degraded quality unofficial discs and online streamable versions have been distributed.

Its plot involves a divorced father who is trying to begin farming while also looking after his two young daughters; in the fields surrounding the farm pesticides are being used, which through the use of intercut actual laboratory images are shown to cause destructive side effects on animals. The titular White Lady is intended to embody the deadly effects of the pesticide and she is portrayed as a white robed spectral presence who masks her true nature under a beatific air.

Her manner and enticements are reminiscent of the White Witch in C.S. Lewis’ popular children’s fantasy novel The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe (1950), who attempts to lure a child to her parallel world and to do her bidding by plying him with Turkish Delight sweets. These “white witches” are not be trusted; the White Witch is a despotic ruler who has kept all of her kingdom frozen in winter, while the White Lady’s true colours are revealed as her beatific mask repeatedly slips.

At one point the White Lady apparently benevolently watches over the daughters as they sleep but is revealed as some form of predatory grim reaper when suddenly the silhouetted arc of a scythe she holds appears over their heads. Later she sits serenely and ethereal Earth Mother-like next to bountiful harvested produce displayed on incongruous tables and white tablecloths in the woods and attempts to entice the daughters to take their fill, accept her (and therefore pesticides) as a bountiful nurturing provider and to leave with her for another world:

“Yes, yes, take… eat… When I am queen, it is strawberries and asparagus all year… I am queen on the planet of light… you shall never be sick there… never die…”

She goes on to gently, slowly and hypnotically begins to say that their father has lost the Earth, that he cannot escape with them and then describe her side effects and how once they have accepted and left with her, she will leave behind changeling replacements to fool their father but that these will carry her “marks” (i.e., genetic mutations).

Eventually she says “All children are mine now… say goodbye to the earth” before fully revealing her true self again, but this time openly in front of their awakened eyes, as she once again appears holding a scythe overhead and looks down at the daughters with a sinister sense of possession. Her bountiful produce is then revealed to be the result of poisonous pesticides, the symbols for which are now shown to be on the white tablecloths as the camera pans across them.

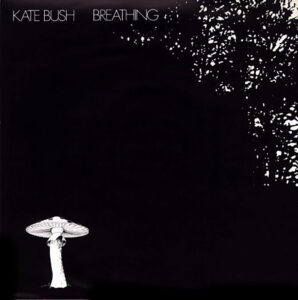

The White Lady’s proclamations to the daughters that: “Each time you have eaten, I have kissed you. Each time you have breathed…” as the pesticide’s symbols are revealed is reminiscent of Kate Bush’s song “Breathing”. Originally released as a single which reached number 16 on UK the charts in 1980 during a period of heightened tensions in the Cold War (and later in the same year featured on the number one album Never for Ever), it takes the viewpoint of an unborn child which has to breathe in deadly fall-out and its mother’s nicotine after an apocalyptic nuclear event. Although initially the song utilises a conventional verse and “catchy” repetitive chorus format, as noted in A Year In The Country: Wandering Through Spectral Fields (2018) it:

“[breaks] from the conventions of what may be expected in a commercially successful pop song, it features an extended unsettling, drifting spoken word passage that describes in a scientific or documentary manner the characteristics of a flash from a nuclear explosion.”

Revisited today the subject matter and at times form of both “Breathing” and White Lady can be considered surprisingly challenging and darkly hued for what were mainstream television broadcasts and music releases, and can be considered as indicators of the vastly changed mainstream popular cultural landscape.

It is difficult to imagine such work as “Breathing” and The White Lady receiving high profile mainstream orientated releases today; there is often a darkness to, for example, contemporary television drama but this is generally utilised for the creation of atmosphere or to create graphic shocks and visual stimulus but it is rarely as explicitly challenging in terms of focusing on the darkness of real-world issues as “Breathing” and “The White Lady” are.