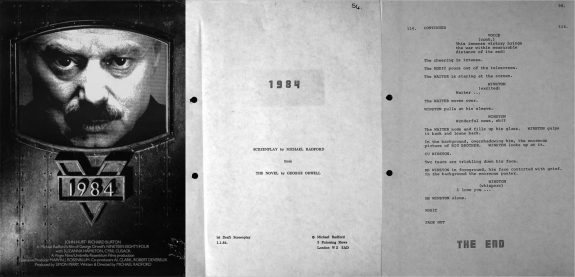

Part 2 of a post Michael Radford’s film adaptation of George Orwell’s novel 1984 (visit Part 1 here).

There is a curious musical aesthetic and controversy to Michael Radford’s version of 1984 which has been most widely seen; Virgin Films who financed its production commissioned the at that time commercially successful British rock/pop duo Eurythmics to produce music for the soundtrack. The film’s director objected to Virgin’s insistence on using the Eurythmics more pop-oriented electronic music and rather wanted the traditional orchestral score that was originally intended for the film to be used, which had been composed entirely by Dominic Muldowney a few months earlier.

Virgin Films exercised their right of final cut and replaced much of Muldowney’s music with that of the Eurythmics. Its director subsequently disowned the Virgin Films edit and withdrew the film from consideration at the BAFTA awards in protest at the change in the score. The Eurythmics responded with a statement saying that they had no prior knowledge of agreements between the director, Muldowney and Virgin and they had accepted to compose music for the film in good faith.

The film with the orchestral score as intended by the director were relatively difficult to see until recently; home releases of the film have generally included the combined Eurythmics/Muldowney soundtrack. A limited edition and now sold out Blu-ray release from 2015 by Twilight Time in North America offered the option of listening to either the orchestral score or the combined one, while a North American MGM DVD from 2003 had just the orchestral score (albeit it the desaturated colours were returned to normal) and some of the non-English language releases have contained the original orchestral score.

However in July 2019 The Criterion Collection are releasing new Blu-rays and DVDs which will have two scores that are listed as being “one by Eurythmics and one by composer Dominic Muldowney”, although at the time of writing I’m not sure if they will be Region A/1 discs which are only playable on Canadian/US or multi-region players.

The elements of Dominic Muldowney’s score which remain in the combined version of the soundtrack in part has a quality that brings to mind pastorally inflected classical music and also brings to mind the soundtrack a totalitarian state may have had created in order to glorify the state, raise up the spirits of its subjects and create a disingenuous smokescreen that obscured the realities of their lives.

Virgin Films was part of the Virgin Group which included the Virgin Records record label and they produced a number of films where there was an attempt to create a marketing synchronicity by including pop music in films and sometimes the performers themselves and also releasing the featured music as singles and albums.

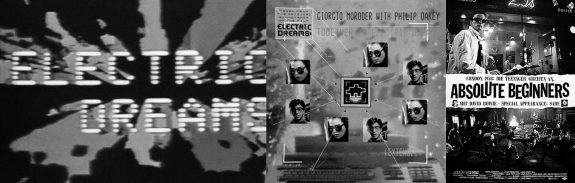

Alongside 1984 these films included the computer/human love triangle film Electric Dreams (1984) directed by Steve Barron and Absolute Beginners (1986) which was a musical adaptation of Colin Macinnes 1958 novel set amongst the youth culture and fringes of 1950s London and directed by Julian Temple.

In comparison with 1984 both Electric Dreams and Absolute Beginners are geared towards being more escapist cinema, although there are serious elements to their stories (the nature of sentience and interactions with digital technology and class and race relations respectively).

To a degree sections of them are nearer to being pop music videos than purely cinematic work, something which may have been heightened as their directors had extensive previous experience in creating pop videos.

Because of the above the use of pop music in Electric Dreams and Absolute Beginners seems relatively fitting. However in 1984 it seems a little out-of-place and adds a certain air of escapist levity to a film which deals with serious issues; it is difficult to listen to the music of a band as well-known as the Eurythmics in this context without to a degree its use in the soundtrack connecting it to the atmosphere of pop music promotional videos.

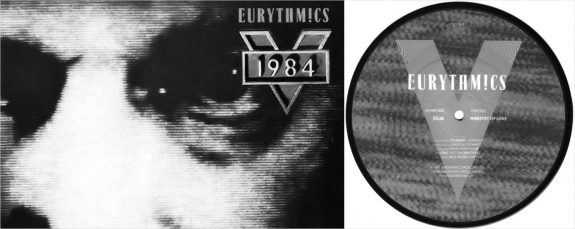

Which is not to denigrate the work of the Eurythmics in this instance; their music for the film has in part a mid-1980s cut-up experimentalism while also retaining its pop sensibilities while their song Julia which plays in its entirety over the closing credits has a beautifully haunting and lamentful quality.

That song has a distinctly pastoral air to it and its lyrics talk of leaves turning from green to brown, autumn shades that come tumbling down, winter leaving branches bare and also of spring rejoicing down the lane. It is effectively a reflection of an imagined call by Winston to his lover Julia and whether their illicit love and indeed themselves will survive amongst the Party’s oppression. It ends with a multiply repeated chorus that plaintively repeats and varies that question in just a few words.

The autumn leaves and shades that come tumbling down in the song also leave behind a carpet where the lovers have laid; this connects to Julia and Winston’s first intimate meeting in the countryside, away from the all-seeing surveillance eye of the telescreens, the Party and Big Brother.

In the film there is a sense in these scenes that the countryside and nature are a still relatively untouched and pure part of the world and they provide an almost brutal contrast with the downbeat nature of life in the city.

However, with a pre-knowledge of the story these sequences have a notably dual and unsettling quality as the door that opens is marked 101; this is the room where the Party utilises and inflicts its detainee’s worse fears on them as part of their brainwashing.

Returning to the lyrics of Julia, in that song after the lyrics talk of a rejoiceful spring arriving there is a mention of a time when everything will be new again. This could be seen as a reference to the cycle of natural renewal, of Winston’s hope for a better future and also a reference to the worn out, make-do nature of the material goods that are available in Airstrip One.

(Three of the principal actors on set during filming.)

The Party’s society is depicted as somewhere woefully short of even basic day-to-day supplies, with Winston and his colleagues constantly looking for and running out of razor blades, while the items and food that are available to all but the highest Party officials are of a low quality.

This is given expression in the film as the shop proprietor that Winston rents the room from runs a second-hand junk shop, the meagre selection of which Winston is shown as browsing and we learn that it is from here that he bought the diary in which he writes his secret rebellious thoughts and there is an implication that such things are not widely available or even prohibited. The shop also sells a number of decorative objects, which Winston does not recognise or appear to have a memory of as the Party’s state appears devoid of such ornamental and beautifying items.

This background to the society in which they live sets the scene for when Julia arrives at their rented room with a few basic good quality foodstuffs such as jam, real coffee and bread; Winston’s surprise and pleasure are palpable as is the sense of shared joy and intimacy which they will provide.

Elsewhere:

- The trailer for Michael Radford’s adaptation of 1984

- The 1984 DVD

- The 1984 Premium Collection Blu-ray

- George Orwell’s 1984

- Eurythmics Julia (in digital audio visual form)

- Eurythmics Julia (in “found on latter day shellac at the online second hand shop” form)

- Eurythmics 1984: For the Love of Big Brother album (in shiny new(ish) fangled compact disc form)

- Electric Dreams trailer (appropriately the “VHS” trailer)

- Absolute Beginners trailer (“from the fabulous fifties, the musical for the eighties… from the book that brought the streets to life… Absolute Beginners is an absolute must… the music, the movement, the romance, the passion…”, well that’s me watching it again tonight. Sigh.)

- Absolute Beginners: 30th Anniversary Edition Blu-ray

- Electric Dreams Blu-ray

- The Criterion Collection release of 1984

Elsewhere at A Year In The Country: