Within “wyrd” and hauntological cultural circles Adam Scovell is perhaps best known for his 2017 non-fiction book Folk Horror: Hours Dreadful and Things Strange which as its title suggests focuses on folk horror in various forms and was, I think, the first non-fiction book which focused on folk horror. He also coined the phrase “urban wyrd” which he used as a way of denoting films etc that he describes as remythologising the fringes, “undercurrents”, “forgotten cracks” and “strangeness of the everyday” of the urban environment; a sort of parallel and interconnected flipside of folk horror.

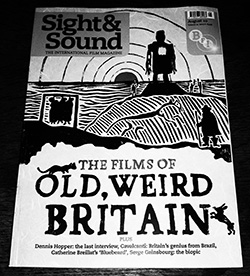

Local Haunts: Non-Fiction 2012-2024, which will be published in April 2025 by Influx Press who have also published three of Scovell’s novels, collects together revised versions of previously published articles etc in which he writes about “the strange connections between place and culture… of the connections between art and the landscapes that inspire it” and which were previously published by, amongst others, Sight & Sound, Literary Hub, Caught By The River, Little White Lies, Port Magazine, The Nightjar and on his own Celluloid Wicker Man site.

The book is split into three overlapping and intertwining sections: it opens with writing that focuses on writers, ends with work that explores film and television and has a “bridging” middle section that includes his travelogue writing and photographs. While some of the chapters are more conventionally journalistic/analytical in character, all three sections contain travelogue elements as they often incorporate writing about his visits and explorations of places which have inspired writers, where films and television were made and/or at times places that don’t directly have a connection with a particular film, writer etc but that when Scovell visited them he found that they resonated with a certain film etc.

The book serves as a fascinating insight into the interests and explorations of its author and his wanderings “off the beaten track” of culture and at times geography. And interestingly in the Introduction he openly admits that while the book:

“…represents a geographical as much as a mental map of the last ten years or so of my life, I am under no illusion that such visits or approaches guarantee any new understanding of particular book, film or anything else…”

This admission places the book apart from the more openly mystical side of geographic-cultural explorations and psychogeography which can at times claim an almost magus or damascene-like connection to and understanding of place and its connections to culture.

(Related to which, it made me chuckle at one point in the book when Scovell says that he was banning the word “liminal” from his dictionary that year, presumably due to its at times preponderance in a certain kind of “high faluting” analytical, academic etc writing.)

At the same time in the book’s chapters there is a sense that it documents a form of, if not exactly mystical pilgrimage, then at least a form of geographic and cultural “dérive” that has been part of him trying to find, explore and unearth the hidden stories of culture and the landscape.

The book includes chapters that focus on writers, films, television etc that interconnect with wyrd and hauntological culture including M.R. James, Alan Garner’s work including The Owl Service and Red Shift, Penda’s Fen, Requiem for a Village and Quatermass but equally it has a broad remit that, at least in relation to the films and television etc it explores, leans towards BFI and broadsheet friendly culture; work which is generally, although not exclusively, more literary and arthouse than say mainstream and mass appeal.

The book has a central focus on “key figures [who] emphasised place in their work” including W.G. Sebald, Agnès Varda, Marguerite Duras and the above mentioned Alan Garner and M.R. James alongside also including writing and explorations of place related to amongst many others the writers, filmmakers, films etc J. G. Ballard, Marcel Proust, Georges Perec, Anita Brookner, Muriel Spark, Harold Pinter, Derek Jarman, Francois Truffaut, Jean-Luc Godard, Chantal Akerman, Blowup, The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoise, The Green Ray.

Inevitably not all of the chapters and the films, writers etc they explore will hold the same amount of interest for all readers but while the book can be read in a conventional linear manner, the standalone nature of each chapter and its cultural and/or geographic areas of exploration lends itself equally to a more selective cherry-picking way of reading it. Or indeed it could well be a book that the reader finds themselves returning to if or when, for example, they have watched a particular film etc that Local Haunts explores but that they didn’t know about when they first bought or read it.

Alongside which while Scovell has a notable depth of cultural knowledge and analysis and an in part academic background – he completed a PhD in 2018 – Local Haunts isn’t a dryly written academic treatise but rather his writing is accessible, personal and personable which in turn makes easily accessible what may at times and for some readers be unknown or esoteric subject matter.

One of my favourite sections, originally published by Caught by the River in 2018, is in the middle travelogue section where Scovell writes about how he stumbled on a double sided row of garages when he was in search of writer Angela Carter’s old house in an area of London that has become an affluent property hotspot and which the contemporary reality of didn’t reflect photos he had seen from the late 1980s which showed the area and Carter’s house as “battered but lived in and filled with eccentric bric-a-brac”:

“The Chase where Carter lived is now… a prime property hotspot. The Clapham I’d come to find had long since passed, or so I thought. It was then that I walked down an alleyway that led to a set of garages behind Carter’s road, and I was whisked sharply away to another realm… [the area was] filled with old garages adorned with green and white rusted doors… The walls all around are cracked and covered with dead leaves. Trees hang over the brickwork and sometimes intermingle with the streetlights. Walking through it quite by chance was like travelling back in time at least thirty years, similar in tone to the images I’d surrounded myself with before moving down to London a couple of years back… [Which included the] strange realms of the [1960s-1980s popular British television series] Callan, The Sweeney, Minder and all those other programmes [which] had seemed to be filmed in an alien world full of open spaces, land left to its own devices and a surreal affordability. That London is as fantastical as Forbidden Planet in comparison to the city today. But these garages were absolutely part of that same world – somewhere the developers have forgotten… Such places that have managed to survive the scrubbing [sanitising effects of gentrification], tell of a time when space was not a defined commodity; when there was still some sense of affordability and even an unfathomable beauty in the ordinary and forgotten brownfields of the capital. There’s no slogan, no catchy marketing brand or price-tag attached to this place. It just is… In the London of today, it is an incredible and lovely thing to find.”

This section, in spirit, reminds me of an opening section of Benjamin Myers non-fiction 2018 book Under the Rock: The Poetry of Place:

“We leave London early one June morning, Della and I. It is a decade ago and all our combined possessions have been crammed into a removal van that left the night before. What remains is shoved into the back of my car… We hit the morning traffic and an hour later are still edging along Vauxhall Bridge Road into Victoria. Our mood is strained, conversation terse. The stress of a house move is underpinned by the knowledge that once you leave the city it is very difficult to return; one only moves to London when either young or wealthy, and now we were neither… Twelve years earlier… I had tracked a similar journey in reverse, driving a borrowed car full of clothes, books, records and treacle down from the north-east of England to find myself circling Piccadilly Circus at five o’clock on a Saturday evening, Eros looking down at me as I attempted a U-turn much to the chagrin of the dozen black cabs caught in my slipstream… Eventually I edged my way south of the river over the same bridge I crossed now, to move into a dilapidated transpontine squat in a labyrinthine Victorian building… Here I lived rent-free for four years… But now it was the height of a recession and London was no city in which to be poor. Where once it was a dizzying maze to be navigated one day at a time, a playground for constant reinvention, now it was a place owned by the property developers, the oligarchs. The old one-bedroomed flat, with its bath on breeze blocks in the kitchen and infestation of mice, abandoned by the local council for thirty years, had recently sold for £800,000.”

In turn Local Haunts could be seen on some levels as being Scovell’s attempts to circumvent, even if only for a psychogeographic day or two’s wandering at a time, the modern day “enclosure” of much of Britain and in particular its “fashionable” city centres that has effectively made it financially prohibitive to live and work in them for much of the population.

Links:

Local Haunts at Influx Press’s site

Adam Scovell’s Celluloid Wicker Man site

Local Haunts at Waterstones

Local Haunts at Amazon UK

Benjamin Myer’s site

Benjamin Myer’s Under the Rock: The Poetry of Place book at Elliot & Thompson’s site

Caught by the River’s site

Sight & Sound at the BFI’s site

Adam Scovell’s Folk Horror: Hours Dreadful and Things Strange at the BFI’s site

Folk Horror: Hours Dreadful and Things Strange at Amazon UK