“I’m talking to a machine. What’s happening to me? I’ve gone nuts.” (Quoted from the film Electric Dreams – in a manner possibly somewhat prescient of interactions with contemporary voice activated computer devices.)

Part 2 of a post on the imagined omnipotence of the 1980s computer in American cinema (visit Part 1 here.)

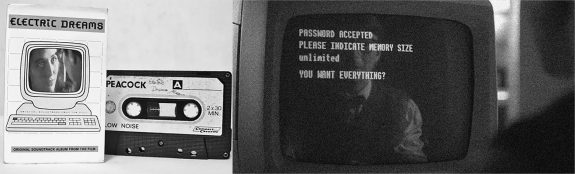

In Steve Barron’s film Electric Dreams, which was released in 1984, a standard shop bought 1980s home PC gains artificial intelligence, sentience and falls in love – seemingly extending its processing power massively by connecting with a government computer over a dial-up modem. As with some of the other above films, this massively conflates the abilities of computers and related technology at the time – in 1984 modems could generally transfer around 9.6 Kilobits per second or around 0.0012 Megabytes. To put that into context a one page word processor text only document today could well be over 800 Kilobits, a compressed high-definition image could well be over 7000 Kilobits in size. So obviously there were some pretty fancy compression algorithms being carried out to enable the transfer of enough computer power to enable the attaining of sentience over a few minutes of dial-up modem data transfer (!).

Alongside gaining artificial intelligence, it can also take over and control the lights etc in its owner’s home, something which is only just becoming even slightly widespread via digital technology today.

However, in Electric Dreams there is still a nod to the realities of the time as the sentient computer is still often interacted with via a standard keyboard text input system and it does not appear to able to visually see, although it can hear and speak.

At the beginning of the film it is also somewhat prescient of modern days habits as in the airport nearly everybody, no matter what age, is seen interacting with a digital device of some sort – games, pocket filing computers etc. At its conclusion it also reflects contemporary trends to the sometimes potentially overwhelming nature of modern technological devices as the computer’s owner and his romantic partner plan to get away from it all, saying happily that they will have “Two weeks with no phone and no TV”.

Elsewhere at A Year In The Country I have talked about how the pace of cinema (and television) today tends to often be rather rapid – or as director John Carpenter put it there are two main ways of making films:

“…one which draws from German Expressionism and allows space for the viewer’s imagination and that which draws from Russian montage and is more concerned with a constant, possibly shallow, stimulation of the viewer which he has referred to as b-bop like.”

Electric Dreams is a forerunner of such things and its director Steve Barron had a history in making pop music videos, which often used a faster pace and editing to keep and catch their audience’s attention in a relatively small amount of time. He has commented that this aspect of making pop music videos fed back into cinema as viewing became more about pace and adrenaline, with audiences looking for a more immediate impact. Indeed viewed now Electric Dreams could in part be seen as a segue of pop music videos, something which also fit with its production by Virgin Pictures Limited which was connected to Virgin Records and which at that time tended to aim towards a promotional synergy by releasing the music from the soundtrack and hopefully it entering the pop music charts.

The potential threat of new technological forms and scientific discoveries being explored in fictional works, particularly when they gain sentience, could be seen to have quite a long lineage, one which stretches back to at least Mary Shelley’s 1818 novel Frankenstein in which a young scientist creates a human like creature in an unorthodox scientific experiment. In that novel the creature goes on to wreak death and destruction but ultimately understands the error or its crimes and vows to destroy itself.

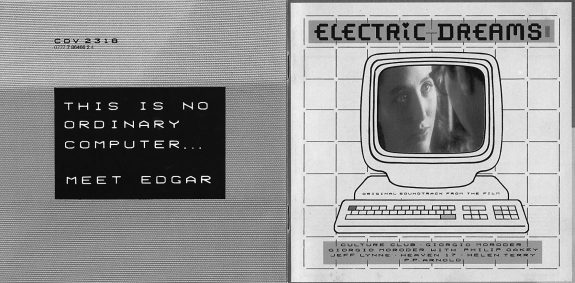

Rather than being a world threatening computer takeover/device of large-scale destruction as in say WarGames or Superman III, Electric Dreams more shows this computer’s intentions as a sort of brattish home invasion pique, where it becomes one corner of a form of love triangle. As in Frankenstein at the end Edgar the computer in Electric Dreams discovers the errors of its ways (and the meaning of love – which it considers to be giving not taking) and carries out a process of self-destruction so that it can leave the human couple alone.

After this at the films ending Electric Dreams also offers another view of the future when Edgar’s voice becomes present in the couple’s car radio and effectively “streams” music and becomes a digital spectre and a form of non-physical cloud computing – taking over and controlling the broadcast facilities of radio stations and removing them from human control.

Giorgio Moroder and Philip Oakey’s iconic Together in Electric Dream’s theme song then begins playing over a finale montage of members of the public dancing in various locations, which has an uplifting feel good quality but also due to the song playing due to Edgar’s and therefore computer’s omnipresence in society, still carries with it a slight undercurrent of, if not overt menace, then at least potential concern about what if this sentient computer power returns to less benevolent aims.

Elsewhere:

Elsewhere at A Year In The Country:

- Looker and the Imagined Omnipotence of the 1980s Computer – Part 1: Wanderings 26/52

- From “Two Tribes” to War Games – The Ascendancy of Apocalyptic Popular Culture: Chapter 13 Book Images

- Week #39/52: An elegy to elegies for the IBM 1401 / notes on a curious intertwining