“Robin Redbreast is a 1970 television programme, which although it was originally made and broadcast in colour, now only a black and white version is known to exist. It contains a plot and atmosphere that draw you in, grip and unsettle you…

(It is not) an as-overtly visual representation of folkloric rites as say The Wicker Man is (apart from one brief moment where the locals gather, clad in folkloric attire, which could almost be a photograph by late 19th/early 20th century documenter of folk customs Benjamin Stone or a modern day re-enactment of his photographs); it does not have the broad cinematic sweep or cult musical accompaniment of that film but this is a different creature.

It is a more intimate, enclosed story, a television play with I expect a relatively small budget, a small cast and a quite limited number of locations but none the worse for it.”

“…some of the most intriguing pieces of work leading up to and during the creation of A Year In The Country have been the introduction and end title sequences to some of those television series and plays from the late 1960s to mid 1970s; this probably extends to around 1980 to take in Children of the Stones (1977), Sky (1975), The Tomorrow People (1973-1979), Noah’s Castle (1979), The Omega Factor (1979) and the final series of Quatermass (1979).

They often seem to represent a very concise, at points quite surreal capturing of the otherly spirit of the various series, related flipside and undercurrents of bucolia, hauntological concerns and a particular era…”

“The intro sequence for The Tomorrow People is a collage of images that include geometric science fiction-esque shapes, a single eyeball, cosmological swirls, a hand opening and closing, a shadowy figure in a doorway etc.

It could be a mixture of the stark, darkly pastoral covers of The Modern Poets series of book covers from the 1960s and 1970s and Julian House of Ghost Box Records’ design work tumbling backwards and forwards through time, filtered somehow through an almost Woolworths-esque take on such things but still having a particularly unsettling air.”

“The Owl Service’s intro sequence mixes and layers imagery that includes tinted largely monochromatic images of the forest, pulsating geometric circles, a candle flame flickering against a black background, hands making bird silhouettes and a mirrored illustration where the same elements can be seen as both owls and flowers.”

“Children of the Stones’ intro is presented in a more realist, visually conventional manner, though it still more than hints at flipside tales of the land.

To a soundtrack of a memorable, spectral, eldritch and wordless choir, it features multiple images of ancient standing stones, variously shown as ominous looming structures, with the sun refracting over them or in a layering of the past and present as they are pictured next to local village housing.”

It is a sort of rurally-set children’s television version of The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976), with a cockney alien and ecological overtones which the promotional information describes somewhat esoterically as:

‘Out of the sky falls a youth, not of this place or time, ‘part-angel, part-waif ’, a youth with powers he can neither control or understand… nature itself rejects him and takes on the cadaverous body of Goodchild in sinister personification of the forces of opposition… He speaks of time travellers ‘Gods you call them’ who had tried again and again to help the people of Earth… Sky must find the mysterious juganet, the cross-over point in time, that is the key to his return to his own dimension.'”

“(In The Changes) black and chain-wearing louche beatnik styled robbers and brigands roam the land and at points the series wanders off into a milder version of Witchfinder General (1968) territory where those who are suspected of using machinery or even saying their names are seen as “wicked sinners” and considered to be witches…

..in one of the memorable phrases from the series overhead electricity (and so on) cables become known as “the bad wires” and people are not able to pass underneath them as this brings a return of The Noise and the madness which compelled people to destroy technology…

The source of The Noise and the machine smashing/rejecting madness is eventually tracked down by Nicky and her companion to a form of sentient lodestone which has been uncovered in quarry workings.

Although it is not explained what this stone is or how it came to be, we are told that it had given magical powers to Merlin in ancient historical times and it is now trying to take Britain back to what it considers to be a better pre-industrial time by psychically inducing the rejection of machinery…

How on earth did this come to be made as children’s entertainment? In particular the first episode where the madness has gripped mankind and the machines are being smashed in the streets: the scenes of which have an unnerving intensity…

…The Changes could be seen as a reflection of some of society’s fears of social breakdown at that time and the threats represented by a reliance on modern technology which needed modern fuel, which was at that time under threat due to a crisis in oil supplies.”

“(The Ash Tree television play from 1975, based on a story by M.R. James) shares some themes with Witchfinder General in its dealing with folk horror and persecution.

M.R. James’ short story was adapted for television by David Rudkin, who for a while seemed to be the go-to chap for otherly Albion-ic television and also wrote Penda’s Fen…

In many ways The Ash Tree could sit quite comfortably amongst the not-so-salubrious fare that littered the faded cinemas of mid 1970s Britain; it has that nasty, unsettling feeling to it that a fair few cinematic releases from that period did, possibly reflecting a wider sense of corruption and malaise in society…

There is little beauty in this landscape and its rolling fields. Bleak is a word that comes to mind; these are moors and feeding grounds full of judgement, punishment, voyeurism and unexplained carrion.”

“(Penda’s Fen) is a tale which takes in the revival of ancient pagan kings, hidden underground government facilities (cities?), left-wing truths, ranting and paranoia, substitute Mary Whitehouse-esque self-appointed moral majority figures, awakening sixth form adolescent sexuality, alternative religious histories and theological study, fancying your local milk man, demons, army cadet forces, William Blake’s Jerusalem, the threat and worry of the never stopping industrial conveyor belt, returning dead classical musicians who wish to see the silver river and verdant valleys but who are actually staring at a flaking brick wall, the battle of religion against older gods, a birthday cake, adoption, fertility, almost breaking the fourth wall self-criticism about himself in David Rudkin’s script, angelic riverside visitations and Kenneth Anger-esque phallic firework dreams…

It could be a head spinning melange and collage of freakish, cult film making but it is not; although in its hour and a half (actually, its first half hour) it manages to have covered more topics than a whole catalogue of other films may do, this is a very cogent and coherent film which at its core deals with conformity, coming of age and mankind’s sacred covenant with the land.’

“Red Shift from 1978 shares some similarities with Penda’s Fen: it is a visionary take on the landscape and its stories and histories, older forms of worship, tales of coming of age and a priggish not always likeable teenage protagonist…

In part it could be seen as an exploration of the literary, intellectual and cultural idea that similar, interconnected things continue to happen in the same places over time, almost as though places become nodes or echo chambers for particular occurrences or a kind of temporal layering occurs: something which is also explored in Nigel Kneale’s The Stone Tape from 1972.”

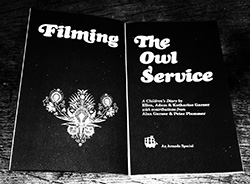

“Filming the Owl Service (1970)… is long out of print and rare as hen’s teeth to find second hand, which is a shame as it is a fine companion piece to the series, full of rather lovely photographs, artifacts, anecdotes, background story, prop sheets and designs from the filming and the series itself.

The book is split into three parts; an “Introduction” by Alan Garner in which he discusses the making of the film, some of what inspired the original book, the coincidences around it and so on, “Our Diaries” by his children who took nine weeks off school while it was being made to be on and around its filming and “Making the Film” by its director Peter Plummer.

Some of the points of interest from the book are:

(Please note: there are 12 such points in the A Year In The Country book.)

5) When Peter Plummer introduced the actors to Alan Garner for the first time and asked if they looked right, Alan Garner’s recollection of it was that it was a “nasty experience”:

“I wanted to run. They looked too right. It was like a waking dream. Here were the people I’d thought about, who’d lived in my head for so long; but now they were real. I couldn’t accept that they were only actors.”

6) Alan Garner had based the part of Huw on Dafydd, an actual gardener from one of the locales of filming, but a Dafydd as he had imagined him being at the age of forty. When he saw them together he said that it “was like seeing father and son”. Apparently the two people in question when they saw one another said:

Dafydd: “I wish I was young and forty again.” Raymond: “Now I know what I’ll look like at eighty.”

The book leaves a sense that Dafydd was a very particular kind of person, one of those people who seem to have been part of the land forever, an archetype almost.

11) Alan Garner is one of the villagers in one scene in the series and apparently he was a foot taller than all the actual local people who were in the series and they all found it hard to behave normally when the man-made storm rain hits them.

Alan Garner: “…as soon as the solid water hit us we all gasped and yelled, and looked like anything but villagers out in a storm.” Dafydd: “We must be dumb and waterproof.”

Alan Garner: “That scene is still odd, because I was about a foot taller than anybody else, and I look like the village freak – which may be what Peter was after all the time.”

12) The end of Alan Garner’s section is a quote taken from a letter sent by Dafydd, referring to the time during the filming and The Stone Of Gronw, which the production had commissioned to be carved, prepared and set in place for the series:

“It was a good time… I have been to the stone. It is lonely now.”

Online images to accompany Chapter 11 of the A Year In The Country: Wandering Through Spectral Fields book, alongside some text extracts from the chapter:

Details of the A Year In The Country: Wandering Through Spectral Fields book and the collection of its accompanying online images can be found at the Book’s Page, which will be added to throughout the year.