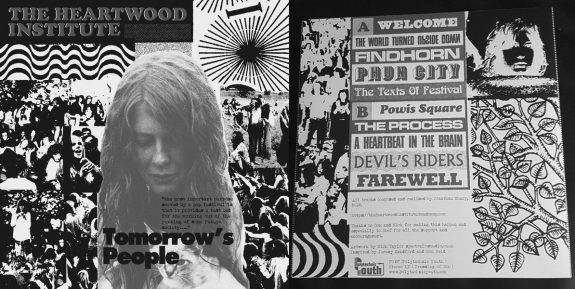

The Heartwood Institute’s Tomorrow’s People is an album of hauntological electronica that draws from distant hazy memories which have an at times darker and transgressive flipside:

“The Heartwood Institute mine the dark underbelly of the electronic psychedelic experience of Britain in the 1970s. Their hauntronica recalls a time when the hippy dream of the 60s had curdled into that peculiar era when black magic and witchcraft was in vogue. The Heartwood Institute is built where Radiophonica meets The Wicker Man. Once inside, you’ll be enveloped by a haze of oscillator fizzes and uncanny folksy weirdness as provoked by the kind of mushroom experience seen in the film ‘Performance’.” Electronic Sound

The album is inspired by a fascination with 1970s counter-culture, alternative ways of living, its darker flipside and/or unravelling and by those who at times, and in part, became society’s folk devils; hippies, bikers, occultists, idealists and activists.

The album also in part draws from related utopian and idealistic events and communities such as the rural idyll and eco village of Findhorn, the Albion Fairs which combined pop festival culture “with the reinvention of traditional rural or nomadic seasonal gatherings, and a back-to-the-land early green ethos” and the Phun City free festival which took place in 1970.

(Phun City was notable for having no fences or admission fee and having security provided by British Hells angels. At the festival “known” performers including MC5, The Pretty Things, Kevin Ayers, Edgar Broughton Band, Mungo Jerry, Pink Fairies and William Burroughs appeared for free after funding was withdrawn).

Such idealistic source material is intertwined with what is described in text which accompanied the album’s release as “fragmenting Ballardian cities choked with uncollected rubbish“; the layering of these elements in the album and its themes could be considered reflective of both the social, political and economic strife which the UK underwent during the 1970s and also the manner in which some sections of society looked to alternative, rural etc ways of life, possibly as a reaction to and/or escape from that strife.

These contrasting aspects of society and history are notably reflected on the track “Findhorn” which combines woozy, pulsing, distorted electronica with more bucolic pastorally inflected folk-ish instrumentation and may well leave the listener not quite knowing whether to bask in a rural idyll or to batten down the hatches against the outside world’s encroaching dread.

The tracks “The World Turned Upside Down” adds a further historical layering to this, as the sampled period voice semi-quotes the 17th century reformer, activist, idealist and communalist Gerrard Winstanley when he spoke of:

“The earth was made by Almighty God to be a common treasury of livelihood for whole mankind in all his branches, without respect of persons… [and the whole of] mankind was made equal, and knit into one body by one spirit of love.”

A clear line can be drawn between the spirit of Winstanley’s words and some of the 1970s post-hippie utopian ideals explored on Tomorrow’s People, albeit the speaker sampled in “The World Upside Down” has revised and adapted them in a more sectarian manner.

(As an aside Gerrard Winstanley was the leader and one of the founders of the English group known to themselves as the True Levellers and by others as Diggers. The group called for the collective ownership of property on the basis of radical religious principles which included a communal sense of existence. They occupied public lands that had been privatised by enclosures, digging them over, pulling down hedges and filling in ditches in order to farm them. Local landowners responded with force and sent hired armed men to beat the Diggers and destroy their colony and although Winstanley protested to the government this was to no avail and eventually the colony was abandoned. If you should be interested, Gerrard Winstanley is the subject of a biographical film by Kevin Brownlow and Andrew Mollo called Winstanley which was released in 1975. The film adds another further layering and intertwining of different eras, their idealism and some of the inspirations for Tomorrow’s People; one of the actors in the film was Sid Rawle, who in real life shared some interests and activist aims with Gerrard Winstanley as he was a campaigner for peace and land rights, a free festival organiser and one of the leaders of the London squatter movement. Quite directly connecting him with Winstanley through the organisation’s name he also formed the Hyde Park Diggers, who campaigned on the issues of land use and ownership. Further layering and intertwining historic idealism and activism “The World Turned Upside Down” is also the name of an English ballad published in the mid 1640s as broadside – a large sheet of paper printed on one side only – as a protest against parliament outlawing traditional English Christmas celebrations and its intention to make Christmas a solemn occasion.)

(Above: repeated images of the 1646 publication of the ballad featuring a woodcut frontspiece.)

(Above: repeated images of the 1646 publication of the ballad featuring a woodcut frontspiece.)

Although the Tomorrow’s People album partly draws from utopian etc post hippie ideals, it is often far from a sunshine and brightness filled view of the world but rather often invokes an atmosphere of dread that seems to reflect a sense of utopian ideals and accompanying ways of life either having turned inwards and corrupted and/or to be under threat by a disapproving and ever more encroaching conventional but fractured wider world.

Although far from unrelentingly dark the listener may well come away with a sense that all is not right in the alternative Albion which the album explores. A number of the other tracks besides “The World Turned Upside” also contain period spoken samples, and also talk of utopian ideals and alternative ways of living but in the album’s overall atmosphere and context they no longer seem to carry their once optimistic intentions but to have been refracted though a glass darkly.

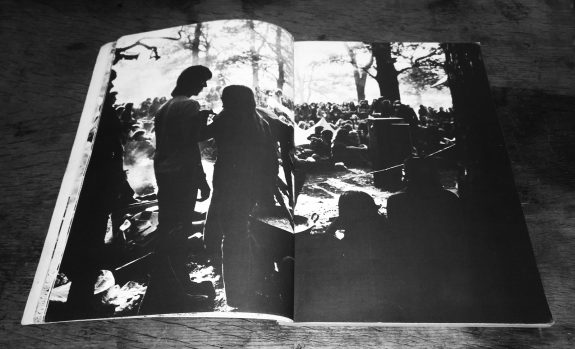

The album’s cover quote and title (I think) are from / inspired by Jeremy Sandford and Ron Reid’s 1974 book Tomorrow’s People which via its text and photography documents British alternative / counter-cultural outdoor festivals in the 1960s and 1970s:

“[The book Tomorrow’s People chronicles] a time when festivals were not an accepted, mainstream, commercially minded activity… [a period in the 1960s and 1970s] when, in part, festivals were an experiment in alternative ways of living and thinking, and were often inspired by hippie, new age, utopian and later anti-authoritarian ideals, and in keeping with their less commercial and non-mainstream nature they sometimes took place without charging an entrance fee. Indeed, such events could be seen as part of an attempt to consciously create short-lived temporary autonomous zones where such experiments and ideals could take place and flourish.” (Quoted from A Year In The Country: Straying From The Pathways.)

This sense of experimentation is reflected in the album’s cover quote, which is credited to Tomorrow’s People:

“The most important purpose served by a pop festival is that it provides a test bed for the working out of the running of some future society…”

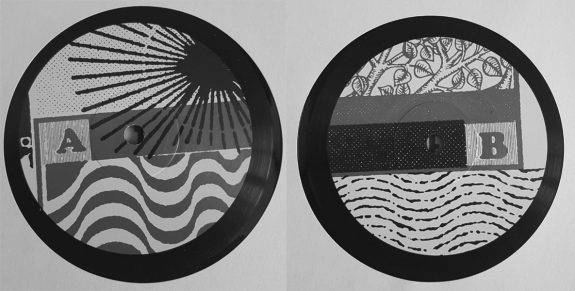

Designed by Nick Taylor of Spectral Studio the album’s front cover art seems to reflect an air of optimism during that period and is a collage of images that create a sense of joyous celebration and communal gathering at festivals. This continues to a degree on the back cover, where it is accompanied by an illustration of tree branches and leaves but it seems to wander down darker pathways.

One of the back sleeve photographs is inverted and this introduces an unsettling atmosphere, which makes the accompanying images of gathered people at a festival, some of whom have had their facial features bleached out by the high contrast of the reproduction, to appear to be an almost zombie herdlike.

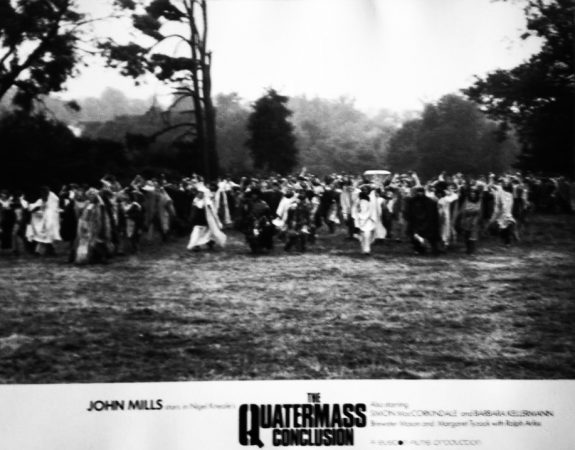

It also brings to mind the relentless and ultimately doomed seeking and gathering of the hippie-like Planet People in Nigel Kneale’s final Quatermass series that was broadcast in 1979, a series which can be read in part as a comment and/or critique of when utopian hippie ideals and alternative ways of living go out of kilter.

(In that series young people gather at the sites of ancient stones and worship, thinking that they will be transcendentally transported to another planet by a visiting entity, when they may actually merely be undergoing a form of harvesting by some unknown extraterrestrial force.)

The sense of a darkening of utopian and alternative ideals in Tomorrow’s People’s artwork is continued on other artwork that accompanies the album, where images of hippie gatherings, festival participants, banners etc are collaged amongst images of hells angels and tabloid newspaper attacks on them, advocates of questionable and extreme lifestyle choices / medical techniques and so on.

The resulting effect could be viewed variously as a fascinating time capsule snapshot, a celebration of alternative ways of life and as containing an almost hellish sense of them having gone awry and become adrift.

Tomorrow’s People was released by Polytechnic Youth. The vinyl is sold out but it is available digitally at The Heartwood Institute’s Bandcamp page.

- Links:

-

- The Heartwood Institute’s Bandcamp page

- Nick Taylor’s Spectral Studio site

- Polytechnic Youth’s website

- Tomorrow’s People (sold out) listing at Norman Records

- Elsewhere at A Year In The Country:

- A Baker’s Dozen Of Professor Bernard Quatermass

- The Stone Tape, Quatermass, The Road and The Twilight Language of Nigel Kneale – Unearthing Tales from Buried Ancient Pasts

- Winstanley – Another Field In England

- Winstanley, A Field in England and The English Civil War Part II – Reflections on Turning Points and Moments When Anything Could Happen

- Tomorrow’s People, further considerations of the past as a foreign country and hauntology away from its more frequent signifiers and imagery

- Barsham Faire 1974 and a Merry Albion Psychedelia

- The Sun in the East – Norfolk & Suffolk Fairs and Albion Unenclosed

- The Tomorrow People (the one on TV!) in The Visitor, a Woolworths-esque filter and travels taken

- The Tomorrow People Intro (the one on TV again)