Wolfen is a 1981 film directed by Michael Wadleigh which could loosely be connected to three films released in that year which took as their themes werewolves, including The Howling and An American Werewolf in London.

It is set in New York and follows a world weary police officer who investigates a serious of vicious murders which are initially believed to possibly be due to animal attacks but as the investigation progresses it becomes clear that it may be connected to an ancient Indian legend about wolf spirits. While in part a film that mixes aspects of genre cinema including horror, science fiction, fantasy and detective story, Wolfen can also be seen to contain exploration and comment on urban decay, renewal, social disenfranchisement and neglect.

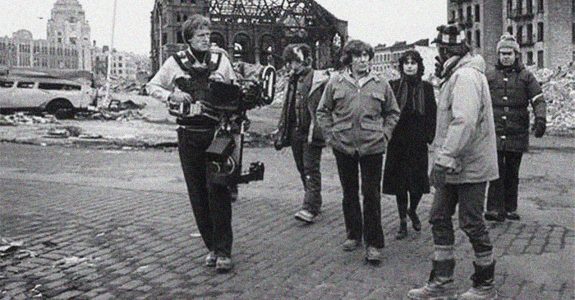

The film is notable in part for its use of real world locations; much of the film shows New York in a pre-gentrification state and the city at points looks akin to a warzone full of derelict and burnt out buildings. These sections were filmed in the South Bronx where at that point urban decay was so rife that only the fire damaged roofless church needed to be built for the film’s production.

Later in Wolfen, despite this being part of a major Western city, this area is shown as being so remote and removed from mainstream life that a police officer can pass down the street with a rifle and nobody comments – in fact there is nobody there to comment.

A background to this urban decay is that two years earlier New York city had narrowly avoided bankrupty and the US as a whole had been facing an economic downturn. By 1977 in some areas of the Bronx unemployment rates were higher than 80% and it was an area that suffered extensively from problems with crime, drugs, poverty, civic neglect and physical decay, all of which would lead US president Ronald Reagan to compare it to London after the Blitz. There had also been an electricity blackout at the height of the summer, leading to chaos, looting and arson. By the later 1970s there were seven different census areas of the Bronx where more than 97 percent of buildings were lost to fire and abandonment. By the time of Wolfen’s filming there had begun to be a slow rise in the real estate market and the city began to move towards a more general financial recovery.

Connected to which Wolfen appears to document a city and culture at a transitional point or phase; it has a gritty downbeat quality that seems to belong more to the 1970s but also seems to reflect upcoming 1980s cinematic depictions of excess and the chasm between rich and poor, particularly in some of its opening scenes where substance-snorting plutocrats are shown taking a joyride in their limousine as they travel to a luxury penthouse in the Financial District and which contrast so strongly with the images of decay in the South Bronx.

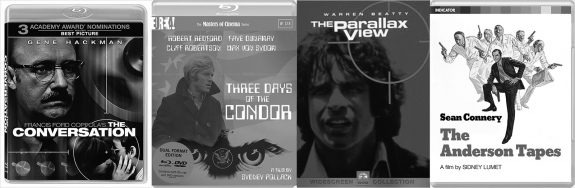

It also connects to 1970s cinema and events in that the attacks are considered by the authorities to possibly by the work of urban guerillas, one of whom when they are brought in for questioning due to her stance and privileged background seems to have been loosely based on American heiress turned radical Patty Hearst. Accompanying which and with a further reference to 1970s cinema such as The Parallax View, 3 Days of the Condor, The Anderson Tapes and The Conversation, which dealt with some similar and interrelated themes, there is a paranoia to the authorities’ concerns and actions and they have access to omnipresent surveillance, an overriding control of flow of news to the media and use cutting edge, possibly illegal scientific monitoring of suspects interrogations, including the use of invisible lie detectors.

Despite its to a degree genre cinema nature, Wolfen works on a number of levels and in some ways its atmosphere and non-frenetic pacing positions it close to independent arthouse film. Also despite the animal attack aspects of the film there is a lack of onscreen gore, particularly in comparison to contemporary genre film making and such aspects are generally shown as just brief flashes rather than being gratuitously dwelled on.

Ultimately Wolfen becomes not a werewolf film, which it initially appears it might be but rather the predators/killers are wolves that have relocated to the inner city (although it does suggest that Indians and wolves may be able to exchange souls). The wolves’ move into the cities is described in this way, after America began to be developed and colonised by Europeans:

“The smartest ones, they went underground. Into the new wilderness – your cities… Into the graveyard of your… species. These great hunters became your scavengers. Your garbage, your abandoned people became their new meat animal.”

Previous to this time, as explained in the film, the Wolfen and Indian tribes coexisted peacefully, with the arrival of the colonisers leading to the dispossession of them both.

As referred to earlier Wolfen could be seen as a parable about urban renewal and exclusion, as the initial murders that the wolves are shown to commit involve a senator who has recently carried out a groundbreaking ceremony of a new real estate area that is intended to be built on their hunting grounds. Towards the end of the story the model of this redeveloped area is destroyed by the main police officer, in order to communicate to the wolves that the threat nolonger exists and he and his companion are not the enemy – but ultimately real world history tells that the wolves lost this particular battle as regeneration of the area went ahead. Accompanying which Wolfen seems to be critical of both urban decay and renewal, suggesting that both are merely different forms of urbicide (i.e. variations on destruction or violence against a city and its character).

However, there is a sense that the wolves will survive whatever changes happen, that they are ultimately higher in the food-chain than humans and in a final voice over the officer says:

“In arrogance man know nothing of what exists. There exists on Earth such as we dare not imagine. Life as certain as our death. Life that will prey on us as we prey on this earth.”

The wolves are depicted as almost mystical, magical or even possibly alien creatures and at one point it is suggested that “they might be god”; this is heightened as whenever the world is shown from their viewpoint the image becomes colourised and highly stylised and voices/noises take on a distorted aspect. This visual effect was created via an early use of an in-camera effect similar to thermography and possibly heightens the sense of the wolves being almost otherworldly creatures as it would later be used to indicate the alien’s point of view in the well-known 1987 film Predator.

Accompanying this mystical inference about the wolves, they are also shown to have become highly evolved above the normal levels of such wild creatures, having a raised intellect and highly tuned senses which enable them to hear even the blink of an eye. It also suggested that they are socially and morally superior to humans as their heightened senses enable them to detect changes in blood levels and body temperature and therefore to detect lies; the film suggests that they have lived for centuries in a sophisticated and even possibly utopian society where, in part because of their sense abilities, dishonesty is non-existent:

“In their world there can be no lies, no crimes. In their eyes you are the savage.”

Michael Wadleigh was removed from the film during post-production by its producers who claimed that the film was late, over budget and too long, although their wish to remove him and recut Wolfen may also have been due to a desire to distance the film from his and its more “message” aspects and resposition it nearer to a standard genre horror film.

In a resulting arbitration case he challenged the producers over his creative rights as a director and attempted to gain the right to show his version to a preview audience before the producers made their final edits and released the version they wanted to. This case lead to changes in the contracts between producers and directors in America, which afterwards cleared spelled out director’s rights to have their cut of a film “previewed before a public audience or screened before a private audience of no fewer than 100 persons of sufficient diversity to obtain an adequate audience reaction.”

(Unfortunately one of the scenes lost in the recutting of the film was of Tom Waits, who apparently Wadleigh was friends with, singing in a tiny dive bar.)

Wadleigh had a background in activism and groundbreaking documentary film making, including Woodstock (1970) which focused on the iconic festival, for which he is said to have produced over 120 miles of footage.

Bearing this in mind and some of the social and political themes which Wolfen focuses on it is a pity that a longer directors cut version of Wolfen does not exist (Wadleigh’s original version is said to have been four hours long). Those themes are still quite prevalent as they are an intrinsic part of the film but it could be possible that a directors version may well have explored them even further but as things stand the possibilities of such a version remain merely intriguing supposition.

However at the time of writing a documentary called Uncovering Wolfen is in production, which promises to explore the film’s themes further and include interviews with Wadleigh.

The director of that is Stewart Buck who, also at the time of writing, also has in production a documentary called A World War II Fairytale: The Making of Michael Mann’s The Keep – another partly genre film from 1983 that also has something of a unique and in this case almost dreamlike character.

The Keep has an apparently lost or never quite existed extended directors cut due in part to its visual effects supervisor passing away two weeks into post-production and nobody else who was working on it knowing how he planned to finish the visual effects scenes. Also the directors original cut was 210 minutes but this was cut by the producers to 96 minutes and

However The Keep appears more lost than Wolfen as Michael Mann seems to not wish to revisit and restore the film, in part because of the lost effects footage and in particular the original ending meaning that the version of the film as originally envisaged is near impossible to create.

Also although it was released on video tape and laser disc and can be purchased/watched via online services it has never had an official DVD or Blu-ray release (although curiously, for a relatively obscure and not overly commercially successful film it did have both a board and role playing game based on it).

Elsewhere:

- Wolfen’s trailer

- Wolfen Blu-ray

- A piece on a 35mm cinema showing of Wolfen and Q&A by Michael Wadleigh

- Wolfen – A Case of Director’s Rights; a period piece at the New York Times on the Wolfen Arbitration Case

- The Press Release for the Uncovering Wolfen Documentary

- The Keep’s Trailer

- The Keep – available to watch digitally

- Details on A World War II Fairytale: The Making of Michael Mann’s The Keep

Elsewhere at A Year In The Country:

- The Dawning of a New Cinematic Age of Surveillance Part 1 – The Anderson Tapes: Wanderings, Explorations and Signposts 47/52

- The Dawning of a New Cinematic Age of Surveillance Part 2 – Three Days of the Condor: Wanderings, Explorations and Signposts 48/52

- The Dawning of a New Cinematic Age of Surveillance Part 3 – The Conversation and The Parallax View: Artifacts: Wanderings, Explorations and Signposts 49/52