Uplifting and gently, melancholically heart breaking at the same time. That seems to make it somewhat appropriate as the title track for Detectorists. A lovely, entrancing contemporary take on folk music.

From time to time, I discover work that seems like an accidental forebear of wyrd culture, and which was created long before the contemporary upsurge of interest in the uncanny, eerie flipside of rural, folk etc orientated culture. An example of this are some of the paintings by Marion Adnams, who lived and worked in Derby from 1898 until her death in 1995. Her work found recognition during her lifetime but for an extended period she became semi-forgotten, and there was not an exhibition devoted to her work for fifty years, until one took place at Derby Museum and Art Gallery in 2017-2018.

Adnams never provided explanations for her work, believing that it should be interpreted as people wished. This non- explanation continues with her painting’s titles, which are often both evocative and intriguingly cryptic (and also at times somewhat presciently wyrd-like), and which include For Lo, Winter is Past and Monkey Harvest.

There is a notable 20th century “classic” surrealist style to some of her paintings, one of which features three wizened and largely leafless trees that seem to be almost dancing in a flat untextured landscape and to have flung their leaves up into the air, while another shows three enigmatic oddly shaped stones again in a flat largely textureless landscape and which are also somehow imbued with human-like qualities as though they are alive and twisting, perhaps talking to one another. Each has a similar sized round hole through its centre and it isn’t clear if these have happened naturally, if they have been created by humans and the stones are a form of ritualistic structures or if the holes have been created by the stones themselves in an unexplained preternatural manner.

When I first Marion Adnams work, it put me in mind of the work of British surrealist painter, war artist, writer, book illustrator, photographer and fabric, poster and stage scenery designer Paul Nash (1889-1946), who has tended to have a higher profile than Adnams.

Nash is said to have found inspiration in “landscapes with elements of ancient history, such as burial mounds, Iron Age hill forts such as Wittenham Clumps and the [henge and ancient stone circles] at Avebury in [the British county of] Wiltshire”, and this in turn seems to presage some of the inspirations and reference points for wyrd or otherly pastoral culture today.

The majority of Nash’s painting are devoid of people, but curiously at times their simplified geometric style, curves etc seem reminiscent of some of artist Tamara de Lempicka’s distinctive and seductive Art Deco portraits and nudes which connects with Nash’s comments in a letter he wrote to a friend in 1912, where he said “I have tried… to paint trees as tho’ they were human beings… because I sincerely love and worship trees and know that they are people and wonderfully beautiful people”.

Nash’s 1911 painting His Vision at Evening features a rolling rural landscape which has a portrait of a woman’s face floating above it whose hair flows outwards to the sides and seems to have become one with or be part of the clouds and sky.

Due to its mixture of mysticism and landscape elements it could be seen as a forebear of some of the more new age and mystical aspects of contemporary wyrd and otherly pastoral culture. It also seems to capture the “visionary” pastoral spirit of music, culture and the landscape that is explored in some of the earlier sections of Rob Young’s 2010 book Electric Eden, where he focuses on, amongst other things, creative work from the 19th and earlier twentieth century. This includes William Morris’ bucolic utopian novel News from Nowhere (1890), and early twentieth-century composers including Vaughan Williams and Holst, of whom Young says, in a manner that connects their work with Nash’s war related artwork which is discussed below, that their work was inspired by “thunderbolts of inspiration from oriental mysticism, angular Modernism and the body blow of the Great War”.

In contrast to the more oblique titles of Marion Adnams’ work, the title of Nash’s war painting We are Making a New World which he created in 1918, appears to be a comment on the destruction wrought by the First World War due to the contrast between its optimistic title and the war-scarred landscape depicted in the painting.

While Nash’s war paintings often have a hellish quality, as in part mentioned above, some of his other landscapes contain a bucolic, gentle, warm atmosphere, while both often feature a sometimes subtle, and at times overt, surreal, Modernist and/or softly geometric aesthetic.

The notable geometric style in some of his work could also be considered a forebear of what I have called the “otherly geometry” of some hauntological and wyrd orientated graphic design and art, including some of Julian House’s artwork for Ghost Box Records, David Chatton Barker’s for Folklore Tapes and some of Nick Taylor’s Spectral Studio work which I have previously described as being “work which often seems to make use of geometric shapes and patterns to invoke a particular kind of otherliness [and allows] a momentary stepping elsewhere”.

Accompanying which, Nash has come to be seen as playing a key role in the development of Modernism in English art, which has been described as:

“…both a philosophical movement and an art movement that, along with cultural trends and changes, arose from wide-scale and far-reaching transformations in Western society during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Among the factors that shaped Modernism were the development of modern industrial societies and the rapid growth of cities, followed then by reactions to the horrors of World War I.” (Quoted from the Wikipedia.com page on Modernism.)

The manner in which Modernism was both a “reaction to the horrors” of conflict and also the modernisation of society, cities, industries etc could be considered part of a cultural and philosophical lineage which in recent years has included hauntological related work’s utilising of Modernist related iconography and culture, such as Brutalist architecture, often coupling this with a sense of Cold War Dread and/or a sense of melancholia or mourning for lost progressive post-Second World War futures.

Interconnected with which Paul Nash’s work and its intersections with wyrd cultural themes etc are included and discussed in the 2021 book Unsettling Landscapes: The Art of the Eerie, written by curator Steve Marshall, writer and former academic Gill Clarke and author and academic Robert Macfarlane. This accompanied an exhibition of paintings, photographs, sculpture etc at St Barbe Museum and Art Gallery in 2022 curated by the book’s authors:

“[The exhibition looks at] the unsettling, strange, gothic and eerie in British landscape art and examines how these ideas have influenced generations of British artists, Surrealism, Neo-Romanticism and on to current pre-occupations with conservation, belonging and hauntology.” (Quoted from text which accompanied the release of Unsettling Landscapes.)

The book includes the below quote from Paul Nash on his 1935 painting Equivalent for Megaliths which has an intriguing “otherly geometry” landscape meets 1980s cyberspace quality and was inspired by the previously mentioned henge and ancient stone circles at Avebury:

“In the fields a few miles north of Marlborough, standing or prone, are the huge stones, remains of the avenue, or the circles of the Temple of Avebury. The appearance of one or more of these megaliths, blotched with ocreish lichens, or livid with the bruises of weathering is sufficiently dramatic in a field of stubble, or in the grass meadows … These groups are impressive as forms opposed to their surroundings… and in the irrational sense, their suggestion of a super- reality. They are dramatic, also, however, as symbols of their antiquity, as hallowed remnants of an almost unknown civilization.”

This in turn provides further lines through the eerie and “unsettling landscapes” of wyrd and hauntological culture as it forebears and interconnects with one of hauntology’s most prominent theorists Mark Fisher’s comments in his 2016 book The Weird and the Eerie on how:

“[Because] the symbolic structures which made sense of [ancient monuments and stone circles] have rotted away… the deep past of humanity is revealed to be in effect an illegible alien civilisation, its rituals and modes of subjectivity unknown to us.”

Director, screenwriter and musician Peter Strickland’s films tend to create their own immersive worlds, often self- contained and separate from wider reality and its markers.

Berberian Sound Studio (2009), his second full length film, is perhaps the most hermetic of his films; it is set in the enclosed world of a recording studio in 1976 and could be considered an homage to and a possible comment on that period’s “giallo” and Italian horror film genres and their sometimes-questionable excesses.

As a loose definition, within cinema giallo generally refers to a sub-genre of work made largely during the 1960s to 1980s, normally Italian in origin and much of which has gone on to gain a cult following. It usually has mystery or thriller elements, often combined with slasher and sometimes supernatural or horror themes and is known for having distinctive, stylish aesthetics.

Berberian Sound Studio involves a garden shed-based British sound effects expert, played by Toby Jones, who travels to Italy to work on a film which turns out unbeknownst to him to be a disturbing giallo horror.

As time passes at the recording studio life and art implode and fall into one another and apart from going to his bedroom he does not seem to leave the studio complex. His sanity crumbles and he becomes increasingly both part of and complicit in a culture and celluloid of misogyny, one which is masked and masquerading as art and the barriers between reality and unreality become increasingly blurred.

Alongside the link to giallo it shares a number of similar themes with David Cronenberg’s science fiction horror film Videodrome (1983); the stepping into an altered reality via recorded media and the degradation of its listeners, watchers and participants.

However, whereas Videodrome has a certain ragged, driving, visceral, hallucinatory and at times street-like energy, Berberian Sound Studio has and creates a more subtle, phantasmagoric dreamlike atmosphere.

It is not a film which intrigues and draws you in through a plot arc, rather it is the imagery, experimentation, atmosphere and its cultural connections. Indeed, plot in a conventional, progressive narrative manner often does not seem to be an overriding concern or intention of Peter Strickland’s. Rather, as referred to previously, his full-length films tend to more be exercises in conjuring and creating particular worlds and atmospheres.

With Berberian Sound Studio the cultural connections include a soundtrack by Broadcast and design/film work by Ghost Box Record’s co-founder Julian House (both of whose work is in various ways interconnected with hauntological and/or wyrd culture) with striking elements of its visual character being created by him. These include the tape packaging, edit sheets etc for the studio setting and as a film it is deeply steeped within such pre-digital recording technology, with its physical form and noises becoming an intrinsic part of the story and its enclosed world.

Julian House’s work also includes an intro sequence for the film within a film called The Equestrian Vortex, which is the one Toby Jones’ character is helping to create the sound effects for. Accompanied by Broadcast’s music this uses found illustration imagery and creates an unsettling, intense sequence which draws from the tropes of folk and occult horror.

The film within a film in Berberian Sound Studio is only shown visually by the illustrated intro sequence, with the violence and excesses of the live action parts only being expressed and implied by the sound effects that are created within the studio setting, guidelines given to the studio engineers or Toby Jones’ character’s repulsion or surprise at them.

Although he demurs at the extreme nature of some of the sequences he is expected to work on, this appears to be only in a British rather polite way. Alongside which, his only connection with back home and a more morally grounded world are the letters from his mother which are initially descriptions of bucolia but which later become their own form of dark horror.

Accompanying which during the film the interior world of the studio is only left when the film breaks through into the British countryside, which provides a brief relief via greenery and daylight. This is in considerable contrast to the corridor, studio, bedroom and night-time courtyard where the remainder of the film is set.

As the film progresses, the nature of the work, the self- contained world of the studio and the manipulative coercion, persuasion, denial or recalcitrance of the other staff seem to combine to corrupt him and they weaken and eventually remove any resistance he has to the nature of the work.

By the end of the film and as a sense of the demarcations between reality and fiction erode Toby Jones’ character becomes as much a facilitator and collaborator in the imagined film’s excesses as those around him.

The themes, actions of the characters etc in Berberian Sound Studio could be seen as questioning the reasoning and motives behind the making of giallo and related horror film, its subsequent cult following and raising up as a form of artistic rather than possibly purely sensationalistic exploitation cinema.

If this is the case then it can be seen as a film which explores and debates viewers’ and makers’ complicit creation and enjoyment of such areas of film, ones which without that elevation could be considered in part to be curious and questionable forms of culture…

Peter Strickland’s films bring to mind those kind of arthouse, sometimes transgressive films that have often gone on to find a cult following but have not always become mainstream critically acceptable.

For example, films that would have once appeared in the pages of Films and Filming magazine which was published from 1954- 1990; often European cult arthouse independent cinema, with leftfield, exploratory and sometimes transgressive or salacious subject matter and presentation.

Both when discussing his own work and in writing by others, there have been numerous mentions of such earlier films which are said to have fed into his and also of a sense of homage that his work contains.

For example, the BFI’s Sight and Sound film magazine called The Duke of Burgundy a “phantasmagoric 70s Euro sex-horror pastiche” and as referred to previously the likes of prolific fringe film maker Jesús Franco are often referenced when writing about the film.

This sense of homage within Peter Strickland’s films can sometimes be quite overt; in his film The Duke of Burgundy the night time dreamlike sequence which sees the screen and one of the main characters consumed by a rapidly layering collage of lepidoptera seems to quite directly visually reference experimental film maker Stan Brakhage’s Mothlight film from 1963 in which layered natural elements and insects to create a rapidly moving montage.

The connections to and lineage of such films via degrees of homage in his work can provide an intriguing cultural layering, acting as pointers to other areas of exploration and on this topic, he has written the following:

“The inclusion of an obscure reference done in an obvious fashion can be precarious in terms of what that reveals about a director’s motivations. At worst, the act of homage is merely posing and diverting attention onto the director rather than the film, but when done organically and effectively, as with both Greenaway at his best and Tarantino, it enriches the film and places it within a wider (albeit self- imposed) lineage that can be rewarding for the curious viewer.” (Quoted from “Peter Strickland: 6 films that fed into The Duke of Burgundy”, bfi.org.uk, 13th February 2015.)

Such earlier films as Mothlight and those of a Scala-esque nature can be culturally and/or aesthetically interesting and intriguing, they may also possibly have a great poster or soundtrack but they are not necessarily always all that easy to sit through in terms of also being forms of entertainment.

However rather than homage, Peter Strickland’s films often seem to more be an evolution of them, taking previous work as some of its initial starting points but then recalibrating their themes, tropes and aesthetics to create work which alongside it containing layered cultural points of interest can also work as entrancing entertainment (albeit that may also at times be more than a little unsettling).

The 2017 album Summer Dancing by Judy Dyble and Andy Lewis is something of a fine cuckoo in pop’s nest which has a curiously contrasting cultural background and set of connections that make it seem as though it should perhaps only really exist in a parallel world left-field pop universe.

Andy Lewis was one the original DJs at Blow Up which is a club night in central London founded in 1993 that had connections to mod and easy listening culture and also in the mid-1990s was a pivotal and notable venue in the development of the Britpop music scene. From 2002 onwards he released a number of number of records on Acid Jazz, alongside collaborating with Paul Weller on the 2007 single “Are You Trying to Be Lonely” which charted in the UK Top 40, after which until 2016 he performed in Paul Weller’s band, who in turn is known for his strong connections with mod culture.

In the 1960s Judy Dyble was the original vocalist in the folk- rock stalwart group Fairport Convention, after which she worked with a group of musicians who in 1968 formed the progressive rock band King Crimson before she made the 1970 album Morning Way as Trader Horne with ex-Them member Jackie McAuley, a record which could be loosely classified as acid or psych folk.

In 1973 she stopped performing and for a number of years ran an audio cassette duplication business before working as a librarian. In more recent years she was featured in an article by Andrew Male and Mike Barnes called “The Lost Women of Folk” in the November 2013 issue of Mojo magazine, alongside Vashti Bunyan, Linda Perhacs and Shelagh Macdonald all of whom for various reasons after the early 1970s largely disappeared from public view for a number of decades.

She made a few guest appearances with Fairport Convention in the 1980s and 1990s but did not begin recording and releasing her own music again until 2003 after which she released a number of albums before passing away in 2020.

Trader Horne’s song “Morning Way” was included on the 2004 compilation Gather in the Mushrooms: The British Acid Folk Underground 1968-1974 which was compiled by author and musician Pete Wiggs, and as I in part discuss in the Introduction both that album and the Trader Horne track on it have a notable position in the history of A Year In The Country; the reimagining of folk on them showed me that folk and rural orientated culture could undertake and explore new, unexpected and even otherworldly journeys and pathways and seemed to open up something in my mind which in turn helped to inspire A Year In The Country.

Judy Dyble and Andy Lewis’ cultural backgrounds are not necessarily ones which you would naturally think of as coming together but rather fortuitously they did in the parallel world left- field pop universe of Summer Dancing and have combined and melded cohesively to produce an album which, while it subtly reflects their joint differing cultural backgrounds and history, has an individual and charming character all of its own.

In text which accompanied its release the album was described as being:

“Made of the very stuff of British psychedelia, an obsession with childhood, the country and the city. It emerges from a place somewhere between Broadcast, the soundtrack to The Wicker Man and Stereolab.”

And on the album’s sleeve it is commented that:

“[The album] began with a chance encounter… [between] two seasoned artists – she a voice of folk and experimental pop past, he a player-producer polymath with ties to the sharp-dressed 60s influenced present… [Although they were born] either side of the 60s, it’s the same culture, history and open attitude that unites the two, as well as rural-urban backgrounds. Church bells, red kites and the stories of E. Nesbit swirl gently in the imagination beside lost loves, London lives and an evergreen… otherness.”

That mention of Broadcast and “an evergreen… otherness” offer a sense of some of the themes and areas which the album explores; as with much of Broadcast’s work, accessible left-field avant pop might be an appropriate genre title and Summer Dancing could be considered to be a more pop orientated accidental counterpart to the psychedelia meets experimental pop “milling around the village” of Broadcast’s 2009 album Mother is the Milky Way.

Alongside both albums exploring some similar musical atmospheres etc, there is also a connection in terms of artwork as Liz Lewis’ cover art for Summer Dancing uses abstract cut up geometric forms which have similarities with Ghost Box Records co-founder Julian House’s artwork and design for Broadcast.

Summer Dancing contains a very English, subtle and charming eccentricity in ways that are difficult to fully define, although it could possibly be in part connected to Judy Dyble’s almost clipped, received pronunciation-esque singing on the record; a description which makes her singing style sound cold or detached but it is in fact anything but.

That subtle, charming eccentricity is also present in An Accidental Musician (2016), a biography that Judy Dyble co-wrote with the prolific author Dave Thompson and which along with the retrospective collections of Judy Dyble’s music Gathering the Threads (2015) and Anthology: Part One (2015), would make a fine companion for Summer Dancing.

In connection to the “lost loves” mentioned on the album sleeve, there is a sadness and even melancholia present on the album, particularly on “A Message” but neither it nor the album as a whole are maudlin, rather they at times contain a joyous remembering and yearning for those who have departed.

While “A Net of Memories (London)” is a psychogeographic wandering in song form around the capital city and connections to it, which tails off into a montage of music and sound where its isolated tones and reversed recordings accompany a radio travel report about swans who have mistaken the road for a river (!)

Nicolas Roeg’s 2007 supernatural horror thriller film Puffball contains a number of different tones in a somewhat intriguing and possibly even surprising manner, including combining a graphic, almost dissolute sexuality with its more realist aspects and it is not an easy film in parts: it is both unsettled and unsettling in various ways.

Set in a remote part of the countryside, it is a television-esque kitchen sink folk horror film that mixes Grand Designs with the music of Kate Bush and what author David Keenan has called England’s Hidden Reverse.

In the film new age-ish imagery intermingles with “Are- they-real or not?” folkloric and witchery shenanigans, tales of fertility battles, fertility ending with ageing and slick yuppie-like outsiders gutting and rebuilding a cottage that was previously the site for intense local loss in a possibly inappropriately modern, minimalist, over-angled style.

In some ways it feels like the story of the old ways battling with the new: of the arrogance of money and man trying to push out the mud and nature of the land. It is also reminiscent of the folk horror-esque Play for Today television drama Robin Redbreast from 19703 in the sense of rural locals entrapping an outsider in fertility rites and rituals and the use of a slightly simple man of the land for those ends.

As an aside, it is loosely connected back to early 1970s folk horror by the appearance of Donald Sutherland, and being directed by Nicolas Roeg, it is but a hop, skip and jump from them to The Wicker Man via Nicolas Roeg’s 1973 film Don’t Look Now, in which Donald Sutherland stars and which was released cinematically in the UK as part of a double bill with The Wicker Man. In Puffball he makes for a striking figure, appearing as an almost slightly deranged happy old owl, albeit one in respectable business garb.

Further connecting Puffball to kitchen sink film and aesthetic, it also features the bird-like late beauty and fascinating screen presence of Rita Tushingham, who appeared in A Taste of Honey 1961), which is known as one of the classic 1960s kitchen sink/ British new wave films; here she is all staring eyes and grasping country ways.

Throughout the film Kate Bush’s song “Prelude” from her 2005 album Aerial, which features the angelic voice of her son accompanying her piano playing, appears and reappears, interconnecting the themes of the film and its stories of progeny to come and those lost.

Puffball is also further connected to Kate Bush’s work through two of its actors: Donald Sutherland appeared in the video for her 1985 single “Cloudbusting”, while one of the film’s lead actors is Miranda Richardson, who was also one of the main cast members in Kate Bush’s The Line, the Cross & the Curve film which accompanied her Red Shoes album from 1994.

The film was also released under the more exploitation friendly title The Devil’s Eyeball (puffballs are large round white fungi, also known by this other name).

The imagery which accompanies The Devil’s Eyeball version of the DVD release makes the film look nearer to a cheap b-movie, teenage friendly take on say the 1984 gothic fantasy-horror film The Company of Wolves, which is in part an adult take on the fairy story Little Red Riding Hood and could be considered an early(ish) example of folk horror due to its tales of deceitful ravenous wolves in the wood.

There’s a review by Cathi Unsworth of A Year In The Country: Wyrd Explorations in issue 456 of Fortean Times:

“In this compendium of journalistic wanderings, [Stephen Prince] connects the strands of a spider’s web of wyrd that combine the elements of [his] formative years to catalogue the fresh awakenings of Old Albion from beneath the Military Industrial Complex.. You’ll find cinematic and televisual representations from The Wicker Man to Kill List, The Owl Service to Detectorists. Music that feeds off such atmospheres – Ghost Box Records, The Eccentronic Research Council and folk music revivalists and revisitors from The Watersons to The Owl Service (the band). Those who made this ground so fertile in the the first place – Alan Garner, Nigel Kneale. And those dedicated to saving sacred archive material Flipside, Talking Pictures TV.” (Quoted from the Fortean Times review.)

The review is a fascinating exploration of the themes in the book and also the wider cultural, social, political and historic background to both the book and interconnected wyrd, otherly Albion-esque, hauntological etc culture in general.

It’s also in good company as Bob Fischer’s regular The Haunted Generation column that he writes for Fortean Times in which he “rounds up the latest news from the parallel worlds of popular hauntology” is on the right hand side of the magazine’s two page spread which includes the Wyrd Explorations review.

Thanks to Cathi Unsworth for the review and David V. Barrett of Fortean Times who commissioned it. Cheers and a tip of the hat to both of them.

Related posts at the A Year In The Country site:

External links:

Folk horror is a cultural genre which as a cultural strand has created ever-growing reverberations and led to and/or inspired more recent work.

One such piece of work is Ben Wheatley’s thoroughly unset- tling film Kill List from 2011. As a film it is an intriguing, fascinating, inspiring and deeply unsettling piece of work. An online discussion about the film said “some pieces of culture are the thing that they purport to be about”; this is a film about evil.

Visually, if not thematically, it shares similarities with the grittier side of social realism British cinema. For a large part the world it represents, although about the lives of somewhat shady mercenaries, is presented in an everyday, social realist, kitchen sink manner.

It does not feel like an esoteric otherly world, at least initially; people are shown having dinner, a couple argues about money and so forth. But something else lurks and creeps in; a symbol is scratched behind a mirror, a descent begins and the mercenaries are drawn into an arcane, hidden world and system.

In many ways the film feels like a sequel to 1973’s iconic folk horror film The Wicker Man, or at least of its direct lineage or spirit, exploring the themes of that film but through a modern-day filter of a corruption that feels total and also curiously banal; there is a sense of occult machinations and organisations but also of just doing a job, of the minutiae of it all.

Although initially set in more urban environments, the film travels to both subterranean and rural areas, presenting characters, folkloric elements and costume which seem to be descendants of or from The Wicker Man but shown through a very dark, nightmarish, hallucinatory contemporary filter.

Whereas in The Wicker Man the isolated society it presents is one set in a rural island idyll, in Kill List the abiding memory is a sense of the actions of the participants often taking place amongst empty, overcast, overlooked, neglected or discarded areas of capitalism and industrial society’s edgelands and hinterlands.

The film utilises tropes from more recent horror and possibly voyeuristic exploitational film but seems to layer and underpin this with what psychogeographic thought has called “the hidden landscape of atmospheres, histories, actions and characters which charge environments”; occult in both the literal and root meaning of hidden.

Mr Wheatley, you have made a fine piece of culture and have captured something indefinable, but it is not an easy piece of work to have around hearth and home…

Halloween III: Season of the Witch is something of a culturally multi-layered film and it is also an odd and intriguing cinematic and cultural experience.

Originally released in 1982, it is not actually a John Carpenter- directed film, rather it is co-produced by him and is part of the Halloween franchise which he instigated. It was directed by Tommy Lee Wallace, who also wrote the final screenplay, and is co-soundtracked by Carpenter in collaboration with Alan Howarth.

How to describe it? Well, if you could imagine a mixture of the 1970s and 1980s work of John Carpenter at one step remove, the takeover and control in Invasion of the Bodysnatchers (1978) or The Stepford Wives (1975) and a more B-movie and less arthouse take on the earlier films of David Cronenberg, all intertwined with the work of Nigel Kneale, then you might not be far off.

I mention Nigel Kneale partly because he wrote the original screenplay and was asked to do so largely because John Carpenter was an admirer of his Quatermass series. Kneale delivered a script that was apparently based more on psychological shocks rather than more conventional horror and physical ones, but Dino De Laurentiis, who owned the film’s distribution rights, wanted more traditional horror and violence in the film. Consequently, director Tommy Lee Wallace revised the script and the subsequent alterations displeased Nigel Kneale so much that he asked for his name to be taken off the finished film.

However, Halloween III still has a surprisingly small amount of gore and violence considering both the above and its genre, with a large portion of such things happening off-screen. Again, with regard to John Carpenter’s films, this is in such marked contrast to the often-gratuitous imagery and special effects of a number of genre films today that it could almost be considered relatively tame in this respect (although at times it still contains quite shocking and unsettling imagery).

Despite his displeasure with the finished script, the spirit of Nigel Kneale remains strong within a film that contains similar themes of the power and significance of standing stones and the collision of ancient powers and rituals with modern science that had featured and sometimes recurred in Nigel Kneale’s previous work.

The plot involves a novelty toy and trick manufacturing company that has incorporated a microchip which includes fragments from one of the stones from Stonehenge into their Halloween masks, which are proving massively popular with the children of the USA. The stone fragments contain a form of ancient power, which via the microchip will be triggered by the flashing images in the company’s television adverts on Halloween, causing the death and sacrifice of the wearers and those nearby, effectively reviving a ritual that last happened 3,000 years ago and bringing about the resurrection of an ancient age of witchcraft. The daughter of a man killed by the company and the doctor who treated him visit the town where the company manufactures the masks and through their investigations, they discover its plans and launch a lone attempt to stop it.

As mentioned previously, Halloween III brings to mind the films Invasion of the Bodysnatchers and The Stepford Wives due in particular to the company’s power over the local town – which is completely run and controlled by the company with the help of electronic surveillance and curfews announced every evening over a tannoy system – and its apparent replacement of the population by androids.

Returning to the work of David Cronenberg, Halloween III also shares some territory and tone with Cronenberg’s Videodrome, which was released around the same time in 1983. In spite of being more overtly B-movie-like than the arthouse-meets- transgression-and-exploitation aesthetic characteristic of Cron- enberg’s film, Halloween III embodies, at times, some of the emotional distance typical of Cronenberg’s work.

Also, as with the manipulative organisation in Videodrome, in Halloween III, despite planning on effectively taking over and changing the world and having the resources to mass-manufacture convincingly human androids, the factory and infrastructure of the novelty manufacturing company seems curiously low-key and non-high tech. It is not presented as a high-end gleaming futuristic corporation, more a smallish, local, paint-chipped operation in a slightly down-at-heel locale.

And in both films, television and video are shown as being utilised for a form of signal transmission which controls the mind and/or causes a physical alteration and mutation or destruction in those who watch it. This connects with a wider use of television in 1980s cinema as being a source of malignant or threatening force – such as in Poltergeist (1982) – with Halloween III’s opening sequence in which CRT television scan lines, pixels and glitches build into the graphic of a Halloween pumpkin, capturing this distinctly period sense of threat particularly well.

John Carpenter and Alan Howarth’s minimal synth score for Halloween III is well worth seeking out and is possibly one of the finest of John Carpenter’s largely electronic soundtracks. Using only a few notes, synth washes and spare percussion, it creates an intriguing, entrancing and seductive atmosphere while also being at times almost subtly, gently and ominously portentous.

The original vinyl and cassette releases of the soundtrack are now quite rare but it has had various reissues: it was first released on CD in 1989; then a complete extended version of the soundtrack was released on the same format by Alan Howarth in 2007 in a limited edition of 1,000; and a vinyl version of the shorter version was initially issued by the Death Waltz Recording Company in 2012 and has since been reissued by them several times and the extended version can also be found on various streaming etc services.

It’s been curious how a number of times as I’ve wandered through the “spectral” cultural fields that make up A Year In The Country, I’ve realised that work I’ve been exploring and writing about was created by people whose work I’d come across long before.

For example, as I wrote in the 2019 book A Year In The Country: Straying From The Pathways, a number of the people who have gone on to create music of a hauntological-esque nature, had previously created trip hop related music that I’d come across back in the 1990s.1 I’d also first explored Julian House of Ghost Box Records work in the late 1990s and early 2000s via the graphic design work he created for the likes of Primal Scream’s XTRMNTR album which was released in 2010, some of Depeche Mode’s hits compilation albums, a book cover design he did for a George Orwell reissue etc.

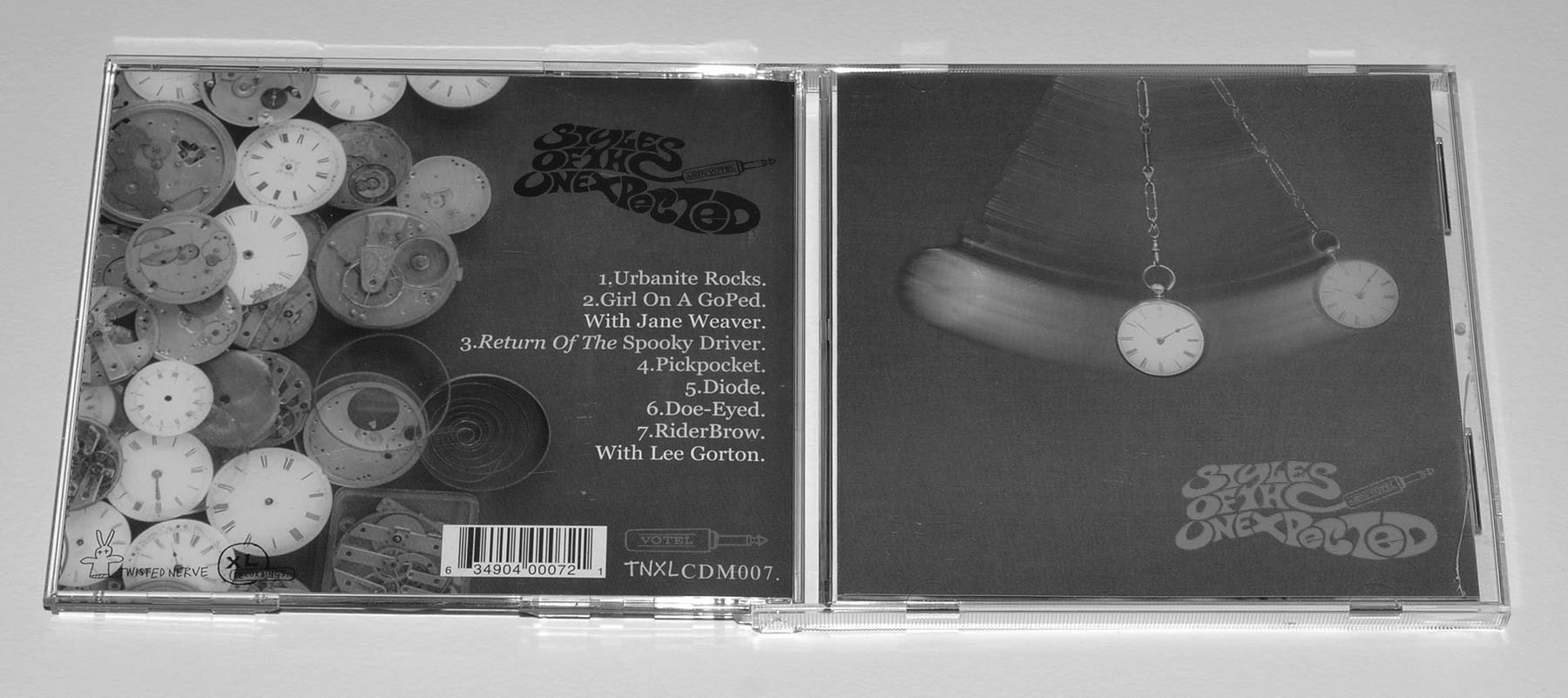

All of which brings me to musician, DJ, record producer, graphic designer and record label co-founder Andy Votel’s2 Style of the Unexpected album; this was originally released in 2000, I think collaboratively, by Twisted Nerve (a label which Andy Votel co-founded in 1997 with Damon Gough aka Badly Drawn Boy prior to Votel co-founding the archival label Finders Keepers Records with Doug Shipton and Don Thomas in 1999) and XL Recordings.

I’d first discovered tracks from Styles of the Unexpected via the indie music orientated music magazine Select (1990-2001) in the early 2000s, which included the album’s “Return of the Spooky Driver” on one of its cover mount CDs.

I had something of a fondness for Select and if memory serves correctly it seemed, particularly towards the end of its run, to in part focus on and offer a more refined or even populist-ly thoughtful, intelligent and eclectic take on indie, electronic etc music than some other mainstream music magazines of the time; a focus that was often reflected on the magazine’s cover mount CDs.

As with much of Andy Votel’s music, Styles of the Unexpected is heavily layered with samples, alongside which much of his work, in whatever area, has involved variations on and been the results of a self-declared obsessive seeking out of work from the hidden corners of culture. This has been accompanied by and incorporated into an often-unexpected layering, juxtapositioning and “recontextualising” of different styles, genres and so on, which has included a “genre defying” catalogue of releases by Finders Keepers Records, and of which he has said:

“I got into buying [the hip hop group’s The Fat Boys and Boogie Down Productions] records when I was about 11 or 12 and was instantly obsessed with the home-made aesthetic of looping other people’s intros and layering culturally disparate forms of music… By the time I was 14 I was also buying heavily sampled records… and looping them inside compact cassettes which my dad had taught me to do with my own voice and sections of [composer and guitarist] John Fahey tapes when I was younger… [Boney and me who I was in the hip hop group Violators of the English Language with] were always looking for our own un-used samples… we started checking out anything remotely psychedelic but making sure it was still obscure and varied enough to be interesting… [and] everything I’ve done creatively since has been a direct progression from my hip hop approach to pursuing obscure music.” (Quoted from “Andy Votel: Questions of Doom”, author unknown, Bad Vibes (gimmebadvibes.com), 2014.)

Revisiting the music on Styles of the Unexpected decades later was a curious thing, as in some ways it seems like both a precursor and a bridge between later 1990s downbeat melodic instrumental trip hop that was often to varying degrees found sound/sample based (think DJ Shadow’s 1996 album Endtroducing, Nightmares on Wax’s 1999 album Carboot Soul etc) and more recent hauntological-orientated electronica.

In particular the above-mentioned track “Return of the Spooky Driver” has a spectral, quietly glitchy melancholia that wouldn’t seem all that out of place amongst contemporary hauntology, which in this instance is spliced and intertwined with driving upbeat interludes that wander towards, but stay shy of, the sometimes almost cartoon-like character of late 1990s big beat music, which often incorporated and could be considered a catchier, more populist and dance-floor friendly flipside to that period’s instrumental trip hop.

The spectral hauntological-esque quality of the track inter- connects with and can be seen as being part of Andy Votel’s deeply running and to a degree hidden in the undergrowth roots in wyrd and hauntological related culture, which stretch back to long before such things had become more culturally prominent.

His first music release was a “Votel Remix” by him and Rick Myers (who was also a member of the previously mentioned group Violators of the English Language) of the track “Sea Mammal” on musician and DJ Mr. Scruff’s The Frolic EP (Part 2) which was released in 1996. This sampled music from the now iconic folk horror film The Wicker Man’s soundtrack and has a loping hypnotic trip hop “vibe” where far off seeming refrains from the soundtrack repeatedly loop in and out.

His second EP, which was also both his first solo record and the first release under the name of Andy Votel, was the 1997 12” EP Hand of Doom. The main track on this was a vocal trip hop- esque cover of heavy metal/rock band Black Sabbath’s “Hand of Doom which was included on their iconic second album Paranoid (1970). When listened to now the EP’s cover of the track is an evocative time capsule of narcoleptically noirish 1990s trip hop aesthetics, while on the B-side one of the tracks samples the also now iconic 1971 folk horror film Blood on Satan’s Claw.

While on his second album, 2002’s All Ten Fingers, the title of the track “The Viy” is a reference to the 1967 Soviet proto folk horror film Viy, which had been released on DVD for the first time in 2001; the music on this track has a quietly haunting background and a subtly exotically folkish sounding plucked refrain that would easily slot into a contemporary folk horror/ wyrd orientated concept album.

Probably the oddest and most “culturally disparate” example of his “deep running… hidden in the undergrowth roots in wyrd and hauntological related culture” is his 1997 remix of the pop rock band Texas’ at that time unreleased single “Say What You Want” which would go on to reach number three in the UK singles chart. His remix samples, amongst other things, the then also unreleased soundtrack to the 1970 surreal coming of age dark fantasy horror film Valerie and her Week of Wonders, which is part of the Czech New Wave of film and which has come to be a prominent touchstone within contemporary wyrd culture.

However, when Votel told the major label which Texas were signed to about the samples he had used on the remix they shelved the release but it was released as a limited white label 12” and can also be listened to online at Finders Keepers Records’ Soundcloud page.

The remix is an intriguingly odd thing to listen to today, a curious slice of culture that seems almost as though it belongs to a parallel world where the “injection” of then (and still to quite a degree) obscure Soviet era film culture into mainstream British pop culture was the norm.

In more recent years between 2010-2012, Andy Votel released music as Anworth Kirk on the Pre-Cert Home Entertainment label and also Folklore Tapes. This pseudonym is taken from the name of one of the locations where The Wicker Man was filmed and the music he created under this name have a notably “spooky” folk horror-esque and pastoral occult-like atmosphere.

As with much of his above-mentioned earlier work they are also more than a little “plunderphonic”-like in their extensive use of found sounds and samples. At times they also veer towards some of the tropes and aesthetics of trip hop, albeit without the loping downbeat drum patterns of trip hop and some of his earlier work, and indeed if the drum patterns etc were added to or stripped away from that earlier work and the Anworth Kirk releases they could quiet easily tumble back and forth and be placed in his releases from over the decades.

There are also other much more overt lines of connection and intersection between Andy Votel’s work and the core of wyrd culture as in 2009 Finders Keepers Records, which as I mentioned above he co-founded, released the Willow’s Songs compilation album which showcased the British folk songs that inspired the soundtrack to The Wicker Man.

Traditional song “Highland Lament”, a different version of which accompanies the opening scenes of the film, is for myself one of the standout tracks on the album and it is one of those times where one song is worth the price of entry on its own.

Its lyrics tell a tale of agricultural dispossession and intriguingly it is not credited to a performer on the album, which in these times of instant knowledge about almost everything being available via online searches adds a certain appealing mystique that I am loath to puncture.

As is often the way with Finders Keepers’ releases, the album is rather nicely packaged, and includes hauntingly ethereal photographs of folk dancers, which once upon a time were probably just ordinary snapshots but the passing of time has added a distant and almost otherworldly air to the photographs.

Finders Keepers Records also reissued David Pinner’s 1967 book Ritual in 2011, the basic idea and structure of which was part of the inspiration for what became The Wicker Man after David Pinner sold the film rights of the book to future Wicker Man cast member Christopher Lee in 1971.

Although the film and book differ in a number of ways, in both a police officer attempts to investigate reports of a missing child in an enclosed rural area and has to deal with psychological trickery, seduction, ancient religious and ritualistic practices.

The Finders Keepers reissue contains an introduction by writer and musician Bob Stanley called “A Note on Ritual”, which serves as an overview of and background to this very particular slice of literature and which deals with pastoral otherliness and the flipside and undercurrents of bucolia and folklore:

“Be warned, like The Wicker Man, it is quite likely to test your dreams of leaving the city for a shady nook by a babbling brook.” (Bob Stanley on Ritual quoted from the book’s Introduction.)

The introduction opens with and explores one of the recurring tropes of folk horror; a sense of how nature can come to almost dwarf you and of how our layers of urban and modern security can easily be dismissed by the ways and whiles of nature.

It captures and conjure the stories and atmosphere of the novel, summoning a sense of the potential wildness of rural life and ways and in its expression of this seems to almost exist as a thing unto itself, separate from the following pages.

Over a number of years Bob Stanley has been collecting and writing about particular niche and at times overlooked areas of music and culture and has curated a number of related compilation albums.

One of these is Gather in The Mushrooms: The British Acid Folk Underground 1968-1974, which was released in 2004 and that in terms of dealing with the flipside of the landscape and folk culture could well be considered a companion piece to his Ritual introduction.

It also links more directly to The Wicker Man in that its opening track is an instrumental version of the song “Corn Riggs” by Magnet, the vocal version of which is included in the film’s soundtrack.

Which in turn interconnects back to the “subterranean wyrd hauntological” roots of Andy Votel’s music as it is also the song from The Wicker Man’s soundtrack that he sampled for his first release, the Votel remix of Mr. Scruff’s “Sea Mammal”.