Andrew Niccol is a New Zealand born screenwriter-director, whose films often seem to wrap quite challenging issues in something of a Hollywood coating. The first film he wrote and directed was Gattaca (1997) in which the genetic modification and screening of human embryos in order to ensure that they possess the superior traits of their parents has become common, as has the genetic testing of employees. Genetic discrimination is illegal but in practice genetic profiling and discrimination is widely used by employers and society in general. Reflecting this the title of the film is based around the letters G, A, T and C which are letters used to represent the four nucleobases of DNA and are some of the molecules identified within genetic science which carry genetic information.

The use of genetic technology has led to a segregated society where those who have been born via this system, known as valids, have much better life choices, access to employment etc and those who have not are known as in-valids and tend to be relegated to menial jobs and are generally considered inferior. This aspect of the film could be seen to be both a comment on the dangers of eugenics and also a remoulding of race, class or caste based segregation:

“I belonged to a new underclass nolonger determined by social status or the colour of your skin… Now we have discrimination down to a science.”

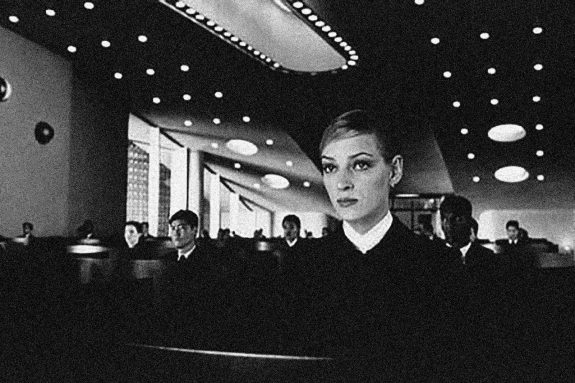

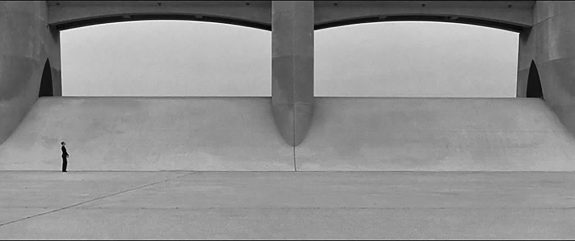

The film appears to be set in the relatively near future or possibly an alternate timeline version of the world in years to come and creates in part a mid century modern or populuxe-esque retro-future vision that makes extensive use of real world locations, featuring modern and at times minimalist/Brutalist concrete architecture of the 1950s, alongside futuristic turbine electric-powered cars based on 1960s car models. The bar/nightclub shown in the film also has a retro cabaret-ish air that would not look out-of-place in more recent revivals of vintage style and fashion. While much of the work is done on computers this is not a society where carrying around mobile digital devices appears to be the norm, apart from small hand-held genetic testing devices which further emphasise the retro-future aspect of Gattaca by having imperfect flickering video displays.

The future that is presented appears to be both quite uniform – all the workers from different social groups dress and have their hair in similar styles – and also notably stylish. This is far from the “burning trash can” crumbling urban vision of densely populated cities in the future that is often depicted in science fiction but rather offers what appears in some ways to be a highly ordered, unbusy, sterile but also beautiful world. This is accompanied by a sense of ache or yearning to the film, that is in part a reflection of its main character’s quest and also possibly due to the arresting, evocative and distinctive nature of Michael Nyman’s score. It is in some ways a dystopia but not one that, at least if you are a valid, appears to cause all that much distress or unrest and the computer based workers at the main complex in the film seem focused, organised and not prone to say gossiping, appearing nearer to a well-dressed and well-behaved industrious but sedate ant colony.

Gattaca’s plot concerns Vincent who is an in-valid but who dreams of a career in space travel but in the normal scheme of things he would be denied this because of his genetic status and he is relegated to a menial job as a cleaner. In order to achieve his dream he has been driven to a form of identity deception known as being a “borrowed ladder” or a de-gene-erate, whereby he uses the genetic material (blood, urine, skin cells, hair etc) of a valid to gain employment at the space-flight conglomerate the Gattaca Aerospace Corporation. In order to do this he has come to live in a symbiotic relationship with his valid whereby he provides for them financially at their home and his valid allows him to use his genetic material in an ongoing basis, which is necessary to avoid detection as at Vincent’s workplace every day testing of workers for their valid status via their genetic material is the norm.

(The film’s imagery also subtly reflects its world’s obsession with genetics; the intro sequence uses microscopic images of human hair and nails – which are collected by the authorities in Gattaca as a way of determining if somebody is a “valid” or not and the spiral staircase in the main appartment featured in the film is reminiscent of a DNA helix.)

Vincent’s “job interview” for his post purely involves his genetic testing via a urine test (in which he substitutes his valid’s), the results of which are considered as being indicative enough of performance and ability without any further discussion. Although he does not look like the valid whose genetic material he is using in the world shown in Gattaca in order to pass security checks etc this does not seem to matter as essentially considerations of genetics has surpassed photographs and visual ways of identifying people.

Choosing a romantic partner is also largely done via genetic testing that is carried out via for example taking a prospective mate’s found or given hair to a business which offers an analysis and screening service. At one point a character offers a potential partner a hair for testing and says “Here, take it, if you’re still interested let me know (i.e. after it has been tested to indicate genetic superiority). While a tester at a screening service who has not physically seen or met one of the character’s potential partners but still says after screening via a hair “9.3, quite a catch”, further indicating that attraction and desirability is no longer predicated on looks or personality.

In terms of the love story aspect of the film to a degree it is a classic “girl/boy from the wrong side of the tracks hides there origins and attempts to live in a higher social strata and a girl/boy from that higher social strata falls for them, discovers the truth and together they fight against unjust societal restrictions that prevent such mingling” plot, albeit in this case being from the wrong side of the tracks is not due to being born to for example an economically deprived background but rather is due to an individual’s genetic makeup.

Curiously when Vincent does finally achieve his long-held wish to go into space it seems like just another day at the office; his preparation seems to have more involved computer work than rigorous physical testing and intriguingly he and the other astronauts enter the spaceship still wearing their normal work suits rather than a space suit.

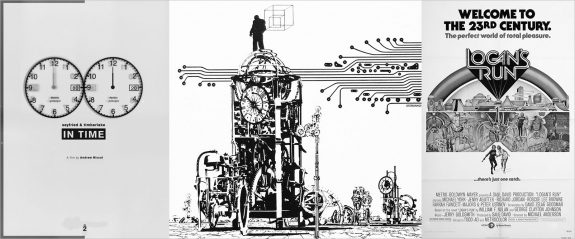

After Gattaca Andrew Nicol went onto write and direct In Time (2011), which while in some ways a genre orientated dystopian science fiction action film also essentially takes forms of social division and inequality and reimagines them. In this film, also set in a near future, people stop ageing at 25 and develop a countdown on their forearm set for a year. This counts down in real-time and when it reaches zero that person “times out” or dies. In this sense it connects with both the film Logan’s Run (1976) where everyone is destroyed when they reach 30 and also to a degree Harlan Ellison’s 1965 short story “‘Repent, Harlequin!’ Said the Ticktockman'” where people have a set amount of time to live which can be revoked – also in both Ellison’s story and In Time the enforcing authorities are known as a Timekeepers and timekeepers respectively.

This not ageing past 25 aspect of the film leads to some curious and striking visual and thematic aspects of the film; a son’s mother appears to be of the same generation as him, multiple generation’s of a husbands relatives when introduced (his mother, daughter and wife) all appear to be debutantes also of the same generation.

In the film time has become the new currency and workers are paid for their labour via it. Within the city where In Time takes place there are distinctly different time zones which it costs a considerable amount of “time” currency to pass between; these are divided between a poor manufacturing area where people are literally “time poor” and an area where the “time rich” live, where people have enough time to be effectively immortal.

The plot is essentially a modern-day take on Robin Hood; Will Salas, a factory worker, is given 116 years by a man who has decided to deliberately “time out” and who explains the realities of the economic system to him as being that the rich hoard most of the time to live forever, while constantly increasing costs to keep poorer people dying:

“For a few to be immortal, many must die.”

Salas enters the richer area (via a taxi ride that literally “costs” him years to pass through different zones) and after a brief period of exploring via his new-found time rich freedom he comes under suspicion for his wealth, is arrested and his time confiscated. He then kidnaps a wealthy businessman’s daughter, flees back to the poorer area where the two bond and begin to rob time banks in order to redistribute time to the needy. These activities escalate in the value of time stolen and given away as they attempt to crash society’s economic system – which appears to happen as now time rich workers downing tools and flooding into the more affluent areas.

A noticeable but not overly referred to aspect of the film is that the forces of law and order in In Time seem curiously under-resourced, possibly as a reflection of a complacent belief that the system is unshakable and ultimately there only appears to be one timekeeper who is overly focused on or tasked with stopping Salas and his partner’s spree of robbery, rampage and wealth redistribution.

In Time shares retro-future styling with Gattaca, in particular via its depiction of futuristic electric cars that are styled on vintage automobiles (the vehicles in In Time were created from older production model modified cars). This appears to be a recurring aspect of Niccol’s film making as in the film Anon (2018) which he wrote and directed the vehicles depicted are also previous era’s models/styles. Anon also shares with Gattaca a use of real world concrete minimalist architecture – although in terms of locations Anon is not as overtly stylised.

Anon is not so much a near future film but rather an extrapolation of the modern world, digital technology and social media. In it privacy and anonymity no longer exist due to everybody having what are called biosyn implants that subject every person to a constant stream of information in their vision, they also make personal information constantly available to everybody else and it records their life down to the millisecond and the resulting information is downloaded to a vast database called “The Ether”, which the police use to find their suspects.

It has been called “an augmented reality neo-noir nightmare” (Bryan Bishop, The Verge) and it is at heart a variation on a detective thriller; the victims in a series of murders appear to have had their vision hacked and replaced with their killer’s viewpoint and the resulting investigation leads the main detective to an anonymous hacker who has somehow managed to disappear from the database.

The technological changes in society are not portrayed as being as clearly negative as in Gattaca and Anon; the stream of information is all-invasive and overbearing to a degree but most of the characters appear to find it useful rather than rebel against it, with the noticeable exception of the anonymous hacker and the technology is portrayed as being put to a good use by the detective in his investigations.

The potential problems of this technology is more shown as a threat only when it has been hijacked to make someone think that they can see things which are not there and which for example causes the detective to exit a road junction into what he thinks is a clear road but which is actually filled with traffic, causing the other cars to crash into him.

Taken as a body of work these three films (and others which Andrew Niccol has worked on such as the enclosed and staged real/virtual-world shown in the film The Truman Show from 1998) could be considered in part to be intriguing high-concept popcorn movies; they are distinctly entertaining while also exploring the effects, changes and threats that can be brought about by modern technology and innovations in a way that is not all that dissimilar to Black Mirror (2011-), the anthology television series created by Charlie Brooker, albeit in a less darkly twisted manner.

Links:

- In Time’s trailer

- Anon’s trailer

- In Time DVD

- Anon DVD

- Gattaca’s trailer

- A Visit to Gattaca’s Real World Architecture

- The Premium Collection Blu-ray / DVD release

- Gattaca – the CD of Michael Nyman’s soundtrack

Elsewhere at A Year In The Country:

- Gattaca – Andrew Niccol’s High-Concept Popcorn Movies Part 1: Wanderings 36/52

- Day #213/365: Artifacts of a curious mini-genre (and misc.)

- No Blade of Grass and Z.P.G. – A Curious Dystopian Mini-Genre: Chapter 28 Book Images

- Robin and Marian – “He has become a legend. Have you ever tried to fight a legend?”: Wanderings, Explorations and Signposts 5/52

- Reflections on Brutalism Part 1 – This Brutal World and a Study of The Shape of the Futures Past: Wanderings 14/52