Director, screenwriter and musician Peter Strickland’s films tend to create their own immersive worlds, often self- contained and separate from wider reality and its markers.

Berberian Sound Studio (2009), his second full length film, is perhaps the most hermetic of his films; it is set in the enclosed world of a recording studio in 1976 and could be considered an homage to and a possible comment on that period’s “giallo” and Italian horror film genres and their sometimes-questionable excesses.

As a loose definition, within cinema giallo generally refers to a sub-genre of work made largely during the 1960s to 1980s, normally Italian in origin and much of which has gone on to gain a cult following. It usually has mystery or thriller elements, often combined with slasher and sometimes supernatural or horror themes and is known for having distinctive, stylish aesthetics.

Berberian Sound Studio involves a garden shed-based British sound effects expert, played by Toby Jones, who travels to Italy to work on a film which turns out unbeknownst to him to be a disturbing giallo horror.

As time passes at the recording studio life and art implode and fall into one another and apart from going to his bedroom he does not seem to leave the studio complex. His sanity crumbles and he becomes increasingly both part of and complicit in a culture and celluloid of misogyny, one which is masked and masquerading as art and the barriers between reality and unreality become increasingly blurred.

Alongside the link to giallo it shares a number of similar themes with David Cronenberg’s science fiction horror film Videodrome (1983); the stepping into an altered reality via recorded media and the degradation of its listeners, watchers and participants.

However, whereas Videodrome has a certain ragged, driving, visceral, hallucinatory and at times street-like energy, Berberian Sound Studio has and creates a more subtle, phantasmagoric dreamlike atmosphere.

It is not a film which intrigues and draws you in through a plot arc, rather it is the imagery, experimentation, atmosphere and its cultural connections. Indeed, plot in a conventional, progressive narrative manner often does not seem to be an overriding concern or intention of Peter Strickland’s. Rather, as referred to previously, his full-length films tend to more be exercises in conjuring and creating particular worlds and atmospheres.

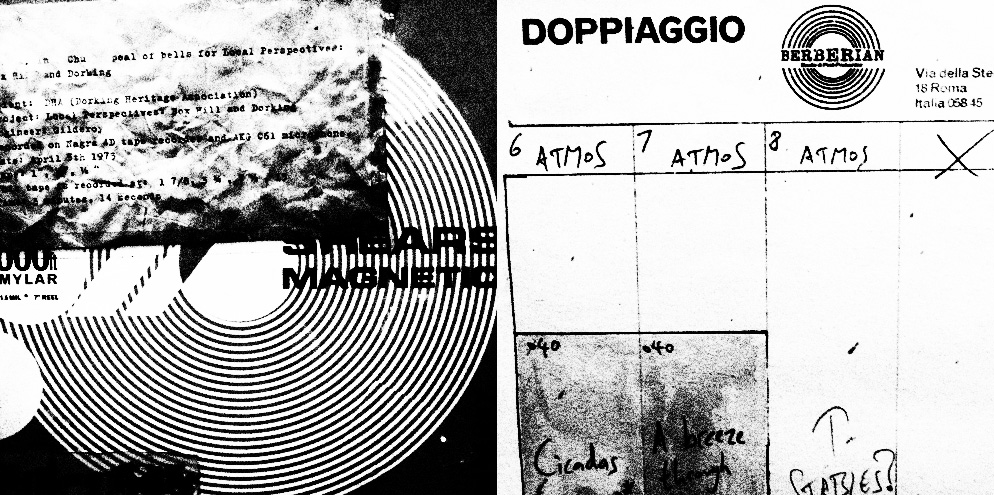

With Berberian Sound Studio the cultural connections include a soundtrack by Broadcast and design/film work by Ghost Box Record’s co-founder Julian House (both of whose work is in various ways interconnected with hauntological and/or wyrd culture) with striking elements of its visual character being created by him. These include the tape packaging, edit sheets etc for the studio setting and as a film it is deeply steeped within such pre-digital recording technology, with its physical form and noises becoming an intrinsic part of the story and its enclosed world.

Julian House’s work also includes an intro sequence for the film within a film called The Equestrian Vortex, which is the one Toby Jones’ character is helping to create the sound effects for. Accompanied by Broadcast’s music this uses found illustration imagery and creates an unsettling, intense sequence which draws from the tropes of folk and occult horror.

The film within a film in Berberian Sound Studio is only shown visually by the illustrated intro sequence, with the violence and excesses of the live action parts only being expressed and implied by the sound effects that are created within the studio setting, guidelines given to the studio engineers or Toby Jones’ character’s repulsion or surprise at them.

Although he demurs at the extreme nature of some of the sequences he is expected to work on, this appears to be only in a British rather polite way. Alongside which, his only connection with back home and a more morally grounded world are the letters from his mother which are initially descriptions of bucolia but which later become their own form of dark horror.

Accompanying which during the film the interior world of the studio is only left when the film breaks through into the British countryside, which provides a brief relief via greenery and daylight. This is in considerable contrast to the corridor, studio, bedroom and night-time courtyard where the remainder of the film is set.

As the film progresses, the nature of the work, the self- contained world of the studio and the manipulative coercion, persuasion, denial or recalcitrance of the other staff seem to combine to corrupt him and they weaken and eventually remove any resistance he has to the nature of the work.

By the end of the film and as a sense of the demarcations between reality and fiction erode Toby Jones’ character becomes as much a facilitator and collaborator in the imagined film’s excesses as those around him.

The themes, actions of the characters etc in Berberian Sound Studio could be seen as questioning the reasoning and motives behind the making of giallo and related horror film, its subsequent cult following and raising up as a form of artistic rather than possibly purely sensationalistic exploitation cinema.

If this is the case then it can be seen as a film which explores and debates viewers’ and makers’ complicit creation and enjoyment of such areas of film, ones which without that elevation could be considered in part to be curious and questionable forms of culture…

Peter Strickland’s films bring to mind those kind of arthouse, sometimes transgressive films that have often gone on to find a cult following but have not always become mainstream critically acceptable.

For example, films that would have once appeared in the pages of Films and Filming magazine which was published from 1954- 1990; often European cult arthouse independent cinema, with leftfield, exploratory and sometimes transgressive or salacious subject matter and presentation.

Both when discussing his own work and in writing by others, there have been numerous mentions of such earlier films which are said to have fed into his and also of a sense of homage that his work contains.

For example, the BFI’s Sight and Sound film magazine called The Duke of Burgundy a “phantasmagoric 70s Euro sex-horror pastiche” and as referred to previously the likes of prolific fringe film maker Jesús Franco are often referenced when writing about the film.

This sense of homage within Peter Strickland’s films can sometimes be quite overt; in his film The Duke of Burgundy the night time dreamlike sequence which sees the screen and one of the main characters consumed by a rapidly layering collage of lepidoptera seems to quite directly visually reference experimental film maker Stan Brakhage’s Mothlight film from 1963 in which layered natural elements and insects to create a rapidly moving montage.

The connections to and lineage of such films via degrees of homage in his work can provide an intriguing cultural layering, acting as pointers to other areas of exploration and on this topic, he has written the following:

“The inclusion of an obscure reference done in an obvious fashion can be precarious in terms of what that reveals about a director’s motivations. At worst, the act of homage is merely posing and diverting attention onto the director rather than the film, but when done organically and effectively, as with both Greenaway at his best and Tarantino, it enriches the film and places it within a wider (albeit self- imposed) lineage that can be rewarding for the curious viewer.” (Quoted from “Peter Strickland: 6 films that fed into The Duke of Burgundy”, bfi.org.uk, 13th February 2015.)

Such earlier films as Mothlight and those of a Scala-esque nature can be culturally and/or aesthetically interesting and intriguing, they may also possibly have a great poster or soundtrack but they are not necessarily always all that easy to sit through in terms of also being forms of entertainment.

However rather than homage, Peter Strickland’s films often seem to more be an evolution of them, taking previous work as some of its initial starting points but then recalibrating their themes, tropes and aesthetics to create work which alongside it containing layered cultural points of interest can also work as entrancing entertainment (albeit that may also at times be more than a little unsettling).