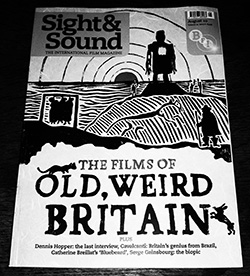

Folk horror is a loosely defined genre or style which creates an alternative, flipside view of the landscape and pastoralism; it draws from and/or is frequently set in the landscape and creates unsettled and unsettling tales and atmospheres, in contrast to more bucolic representations of the countryside as a place of calm and restful escape.

Related work may include elements of a more hauntological nature rather than being purely rurally based and can take in the hidden and layered histories within places and there is often a sense of their inhabitants living in, or becoming isolated from, the wider world, allowing moral beliefs to become untethered from the dominant norms and allowing the space for ritualistic, occult, supernatural or preternatural events and actions to occur.

As a phrase, “folk horror” often conjures images of a trio of British films released between 1968 and 1973 which have become somewhat iconic: Witchfinder General (1968), The Blood on Satan’s Claw (1971) and The Wicker Man (1973).

Looking back today such films could be seen as a result or offshoot of there being at the time of their production, a growing interest in folk music and culture, which was accompanied by a romantic sense of wishing to return to and embrace simpler and more natural or rural ways of living. However rather than being an expression of such inclinations and idyllic bucolia, folk horror’s often bleak nihilistic nature and stories seem to be more an expression of the souring of related dreams and yearnings and in terms of the above films, a rural and folk reflected curdling of 1960s utopian optimism as it entered the 1970s.

This trio of films are not always easy films to watch and particularly the first two, which respectively centre around the sadistic and opportunistic activities of a witchhunter in 17th century England and a rural village where the younger residents fall under the influence of a demonic presence after a farmer unearths a mysterious deformed skull, could be seen as sharing ground with exploitation cinema. Along which lines, both Witchfinder General and The Blood on Satan’s Claw featured Tony Tenser as their executive producer.

Tony Tenser had a cinematic background as a producer in the more lurid side of the film industry – more Soho backstreet than high-end Cannes – producing titillating and/or exploitation pseudo-documentaries such as Naked as Nature Intended (1961), Primitive London and London in the Raw (both 1965), which provided often prurient views of naturism and events in the capital as their prime exploitation selling points. Related to which Witchfinder General and The Blood on Satan’s Claw are films which could be seen to have their roots and onscreen expression in both the more arthouse inclinations of their directors (Michael Reeves and Piers Haggard respectively) and the exploitation aspects of their producer Tony Tenser. However, although over time critical appreciation of them has tended to tip more towards the arthouse side of things, without both sides of this coin one could debate whether these films would have existed or have come to be such resonant cultural artifacts.

Their visceral, more shocking exploitation-esque moments may be part of what has helped to create their cult appeal and have become confluent with consideration of them as films which also explore such themes in a more layered, explorative manner than that which may be found in more strictly straightforward exploitation work or some areas of mainstream cinema.

Tony Tenser and his exploitation orientated sensibilities seems to have been partly responsible for a considerable portion of the late 1960s/early 1970s arrival of what has since come to be known as folk horror as he was also executive producer on Curse of the Crimson Altar (1968). This explores and utilises some of the themes of folk horror (a rural setting, connections to the old beliefs and magic) and centres around the activities of a witchcraft cult at a remote country house; an antiques dealer visits the house as it was the last known whereabouts of his brother before he went missing and he subsequently finds himself drawn into the cult’s nefarious activities.

The film is particularly memorable in its conjuring up of phantasmagorical occult scenes, which are made all the more striking by a film-stealing Barbara Steele as Lavina Morley, Black Witch of Greymarsh, who is dressed in striking, opulent and almost surreal folkloric garb, including a behorned headdress. She serves as mistress of the film’s woozily transgressive dreamlike ritual ceremonies, helping create almost a film within a film; one which seems quite separate to the more mainstream and fairly conventional presentation of the film as a whole.

These scenes, as with The Blood on Satan’s Claw and Witchfinder General, borrow from the more sensational aspects of exploitation cinema while intertwining such elements with something of a more layered, exploratory cinematic aspect.

The late 1960s to around the mid 1970s was the main era for the production of the initial and now iconic examples of film and television that have come to be known as folk horror. However, in terms of cinematic forebears, around 1960 there was a small grouping of horror and/or supernatural films which could be seen as being part of a lineage that would one day become or bring about what is known as folk horror.

These include Mario Bava’s Black Sunday from 1960, also starring Barbara Steele, Jack Clayton’s The Innocents from 1961 and Roger Vadim’s Et Mourir De Plaisir (or Blood and Roses to use its American title) from 1960. Their tone and expression vary from the classic black and white gothic and grotesque horror of Black Sunday to the almost decadent aristocratic Technicolor sensuality of Et Mourir de Plaisir via the repressed supernatural hauntings amongst the reeds of the British countryside in The Innocents.

All of these films are set rurally, but it is not this which causes them to be gathered together in this way (and as commented on above what has come to be known as folk horror does not have to be exclusively set rurally); it is something more subtle and underlying, possibly something in their atmosphere, their spirit and a sense that they are telling the stories of unsettled landscapes.

As with the later films that are mentioned above, these early 1960s films variously contain a curious and intriguing mixture of mainstream, transgressive, at times exploitation and arthouse cinema, the themes and tropes of which are used and explored to create rather classy, exploratory and nuanced work.