From what I remember George Orwell’s dystopian novel 1984 was big news in the year 1984 and was featured in the press etc a fair bit. I think I read it for the first time then – and while I was probably reading it as part of a way of feeling grown up and sophisticated I expect I took it more as a grim piece of science fiction/fantasy rather than as a work of political and social comment.

Originally published in 1949 and set in 1984 it features protagonist Winston Smith who lives in Great Britain, now renamed Airstrip One and which has become a province of a superstate called Oceania. This state is ruled in a totalitarian manner by the “Party”, headed by its possibly imaginary figurehead Big Brother. The Party has created a highly stratified society in which individualism and independent thinking are persecuted, sex may only be used for reproduction, historical revisionism is rife and institutionalised and many of its “citizens” are kept in a state of austere poverty and subject to constant surveillance. Smith appears to be a diligent and skillful worker but he secretly hates the Party and dreams of rebellion again Big Brother, which he carries out through writing subversive thoughts in a secret diary hidden out of view of the telescreens and entering into a forbidden intimate relationship with a fellow employee Julia.

The book has become iconic and a number of its terms and phrases such as Big Brother (the oppressive all-seeing leader), Room 101 (the place where your worst fears are realised) and Newspeak (a restricted form of language created by the Party in order to limit freedom of thought) have become part of common usage.

Part of the focus on the novel in the year 1984 included the release of a cinema adaptation written and directed by Michael Radford, which is said to have been filmed in and around London at the time in which Orwell imagined the story to be set.

It creates an atemporal parallel world vision of Britain which is in parts a pre-steampunk retro-future and although set in 1984 stylistically it seems to hark back more to an alternate take on the 1930s, possibly the 1940s and also combines elements of the imagery, grandiosity and self-regard of German and Russian design from that period.

In this version of the world society and people’s homes are observed by two-way telescreens, while at Winston’s place of work information is accessed from and written to data systems which are operated via traditional rotary dial phones and delivered by both screen and physically via a pneumatic tube system. There are further elements which show a mixing of different levels of technological development; floating fortresses are mentioned, the state utilises rickety and old-fashioned looking helicopters in its surveillance, rockets are used in conflicts but steam trains are also still in use.

The palette of the film has a desaturated look due to the use by cinematographer Roger Deakin’s use of a film processing technique called bleach bypass, which creates a worn and browbeaten atmosphere to the film. Accompanying which the city in which Winston lives is shown as a crumbling, rubble strewn landscape, which now seems so cinematically familiar that despite the totalitarian strictures of life as a setting it is, at least initially, almost comforting. It is only when he is arrested for subversive activities and thoughts (the “sexcrime” of his relationship with Julia, his “thoughtcrime” via his diary and reading of banned political literature) that the true horror of the society which the Party has created becomes apparent.

(The rubble strewn and run down cityscapes of 1984 could also be connected to contemporary British at the time of the films making in that they could be seen as a reflection of industrial decline and what some have considered to be the Conservative government’s attack on or even destruction of more traditional industries, coal mining etc and their connected communities; something which is also reflected in a possible interpretation of nuclear apocalypse television drama Threads which was released in the same year as 1984.)

Once captured Winston is tortured and brainwashed in a manner which is vividly, brutally and grimly, albeit not exploitatively, realised and which is physically hard to watch and that can stay with and haunts the viewer for weeks afterwards. While earlier in the film it could be watched on a more purely entertainment orientated level, at this point it is apparent that this is film and story which is a far remove from merely escapist cinema. It becomes a depiction of the potential realities of the methods of totalitarian dictatorships and man’s ability to behave inhumanely in pursuit of belief systems.

In the film (and the novel) Winston rents a room above a shop from its seemingly open-minded proprietor and meets his lover Julia there. They have a brief few months of secret liaisons, freedom and physical intimacy before their arrest, torture and brainwashing. The style and utilitarian nature of the room in the film brings to mind austere historical images of 1930s-1950s working class Britain and in this sense along with it being the setting for a love and intimacy which society has deemed forbidden it could be seen as connected to fictional period depictions of hidden and persecuted same-sex lovers such as in Neil Bartlett’s novel Mr Clive and Mr Page (1996) in which a couple must meet behind closed doors due to society’s disapproval and even criminalisation of their actions and feelings.

It could also be connected to the heartbreaking and evocative “Valerie’s Letter” section of Alan Moore and David Lloyd’s V for Vendetta comic book series (1982-1989) in which, as in 1984, a totalitarian government rules a bleak and austere future Britain which seems to contain elements of both the present, past and future.

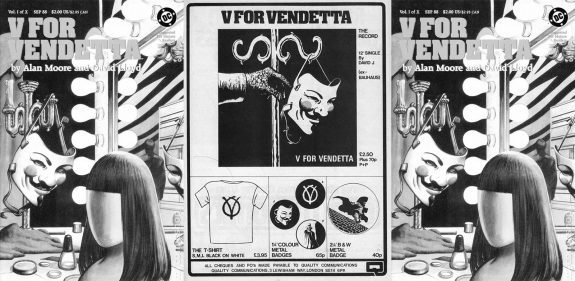

(Above: a cover from the DC Comics’ releases which republished/completed V for Vendetta and a merchandise page from it’s original publication in Quality’s Warrior comic anthology – including David J of Bauhaus’ soundtrack, which in 2019 has been rereleased in a new expanded vinyl edition by Glass Modern.)

“Valerie’s Letter” is an autobiographical note which is found by a prisoner of the state in her cell and which tells of an actresses experiences and struggles and the happiness she finds with her same-sex lover Ruth. It goes on to tell about how “after the war” they began to round-up various minority groups, with Ruth being taken and tortured into giving Valerie’s name and signing a statement saying she had seduced Ruth.

In the note Valerie talks of how integrity is the very last inch of us but “within that inch we are free”, that her lover took her own life as she couldn’t live with betraying her and “giving up that last inch”. She goes on to say that she knows she will die during her imprisonment and that every inch of her will perish except this final inch – i.e. her integrity, belief and love.

While Valerie’s letter is fatalistic, its belief in the strength of this last inch leaves the reader with a sense of hope and resistance in the face of oppression. However 1984’s system of control is ultimately shown as bleakly omnipotent in this sense; prior to their capture WInston and Julia talk of how the Party cannot take away their love for one another but when Winston is subjected to a psychological torture based around his worst fear (rats in his case) he betrays her and that final inch is taken away.

In the film’s final scenes Winston is shown sat on his own in a cafe reserved for condemned traitors, where they sit out their final days in a form of aimless leisure time. Behind him on a telescreen plays footage of him denouncing himself and his crimes; he is at a sort of subdued or even sedated peace but he has had his spirit broken by the Party and there is a sense now that he truly loves and supports Big Brother.

Michael Radford’s version of 1984 has a convincing cinematic quality which can sometimes be lacking in British produced non-realist film and television which, as I have mentioned at A Year In The Country before, can sometimes retain a certain clunky Children’s Film Foundation-esque almost amateurism to it, particularly in comparison to other countries’ output (although admittedly that aspect can also be part of its appeal).

1984 is not necessarily an easy viewing experience, although it has in part a certain almost ravishingly beautiful aspect to its imagery and design, which at times curiously seems to reflect and connect to the aesthetics of 1980’s pop music promotional videos…

…more on which in Part 2 (which, depending on when you’re reading this, may still be in “Coming Soon” status).

Elsewhere:

- The trailer for Michael Radford’s adaptation of 1984

- The 1984 DVD

- The 1984 Premium Collection Blu-ray

- George Orwell’s 1984

- Alan Moore and David Lloyd’s V for Vendetta

- Neil Bartlett’s Mr Clive and Mr Page

- David J’s V for Vendetta Grande Edition reissue by Glass Modern

Elsewhere at A Year In The Country: