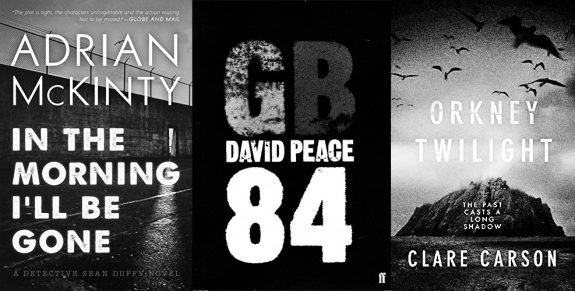

Tony White’s The Fountain in the Forest could be considered part of a genre where noir-esque, genre and crime fiction is used as a way of exploring hidden or semi-forgotten/unearthed history, in a similar manner to say David Peace’s GB84 (2004), Clare Carson’s Orkney Twilight (2015) and Adrian McKinty’s In the Morning I’ll Be Gone, which are set amongst the turbulence within British politics around approximately 1984-1985 and to varying degrees the 1984-1985 UK Miner’s Strike.

These novels all could also be seen as related explorations of “the at times murky, ambiguous actions, participants and organisations of those involved”. (From a previous post at A Year In The Country.)

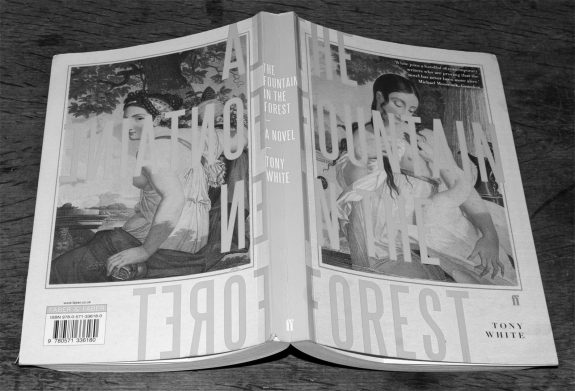

In The Fountain in the Forest a detective called Rex King investigates a murder committed in a central London theatre and time/location at points shifts from modern-day London to an abandoned and squatted village in rural 1980s France, from which the novel takes its name and the Battle of the Beanfield at Stonehenge.

At its core it hinges on a 90 day period of 1985 between the just mentioned Miner’s Strike and The Battle of the Beanfield, which is described as an interregnum – i.e. a period when normal government is suspended – and the book’s blurb says this was a “moment when Thatcher’s militia fatally wounded the British political counterculture”. This was a period which could be to seen to be a moment of:

“…change and upheaval within British society, turning points when there were conflicts between different belief systems/power structures, battles between the old ways and the new.” (From a previous post at A Year In The Country.)

(As an aside the UK Miner’s Strike was a bitterly fought conflict between miner’s and the Coal Board/government of the day over pit closures, while the Battle of the Beanfield saw over 1000 police officers preventing a new age – and others – convoy of vehicles from setting up a free festival at Stonehenge. Both saw actions by the authorities that have been viewed as controversial and at times particularly heavy-handed/violent.)

In a previous post at A Year In The Country I talked about the settings of GB84, Orkney Twilight and In The Morning I’ll Be Gone:

“Although not exclusively set within rural areas, the above three novels often focus on actions that are away from large-scale cities and capitals, with there being an at times underlying sense that these are areas which are a step or two away from the norms of civilisation; they are shown as being unobserved frontiers or edgelands where the rule of law is suspended, where conflicts can be settled in a more brutal, basic manner and crimes or what are considered transgressions against the powers that be’s intentions are dealt with and punished in an almost medieval way.”

The Fountain in the Forest has a similar take on rural areas; the squatted rural village is in a remote, hard to get to area and run as a non-hierarchical commune away from “normal” societies rules and strictures, while the new age and others convoy is also a loose, non-hierarchical gathering where people choose to live alternative lifestyles. Both are physically destroyed, with the authorities actions against the convoy in particular – vehicles were smashed and set on fire, members beaten etc – bringing to mind more the putting down of a rebellion in a far-flung century than actions that would be expected in a supposedly modern twentieth century western democracy.

As mentioned at the start of this post, all these novels utilise crime fiction and can be considered readable, accessible – if not always light reading – fictional works. However as mentioned previously at A Year In The Country, GB84 is “stylistically left of centre or even possibly borderline experimental”. While its use of language and atmosphere is generally more conventional than GB84, The Fountain in the Forest is more overtly formally avant-garde in a number of senses; these include its use of techniques associated with Oulipo, who were a group of mathematicians and writers who produced work according to set rules and constraints (for example George Perecs’ novel A Void featured no words with the letter “e”).

The author forces himself to use a mandated vocabulary and includes the words that make up the answers to the Guardian newspaper’s Quick Crossword from the central 90 day period in which the novel is set. These words are bolded throughout the text and effectively mean it is imbued and layered with a spectral sense of a past era – in the Author’s Notes Tony White mentions how he completed these crosswords at the time and that writing these words out activated a kind of linguistic “muscle memory” as well as offering a linguistic and historical time capsule of the period, alongside a pantheon of historical figures.

Adding to this formal experimentalism, each chapter name is taken from the French revolutionary rural calendar. This was created post-1789 and utilised a radical new form of timekeeping that utilised a 10 day week named after different items from rural life, such as herbs, foodstuff, livestock, tools etc. In comparison with the more traditional calendar these names were intended to have a secular, non-royal and non-hierachical basis and they include the likes of Mandragore (Mandrake), Sylvie (Anemone), Vélar (Hedge Mustard) and Cordeau (Twine).

Although The Fountain in the Forest is in large part set in contemporary London, these sections seem to almost belong to or harken to a past age or be a snapshot of a lost London; a time when it was possible/affordable for “ordinary” people to live and buy homes in very central London. Perhaps also because many of the locations described are ones I was once very familiar with and indeed regularly visited I also brought to it a sense of my own past and related loss.

There is also a sense of wider loss, of the freedom in a pre-digital age to start your life over again truly free of the baggage and constraints of your previous life, when the central character creates a new semi-forged identity for himself:

“As soon as the new passport had come through, Rex… had got up under the cover of darkness and hitched a ride to London. Started over, in the days when you could still do that.”

Throughout the book there is an ongoing sense of timeslip; the description of the last free Stonehenge free festival in 1984 in terms of its cultural reference points, seems more like a late 1960s/early-to-mid 1970s hippie drugfest – although as I have mentioned at A Year In The Country before, there is at points something of a crossover between 1960s hippie culture and 1980s new age travellers and anarcho/crusty punks. The hairstyles may have been different but their rejection of mainstream societal norms shared a number of similarities in its expression.

The book is also initially divided into distinctive parts, with each one generally taking place in a particular location and timezone and there not an obvious connection between them. Towards the end these sections begin to merge into one in an almost maelstrom manner that reflects the conflict and dismemberment of a way of life that happened at the Battle of the Beanfield and which is depicted in the text.

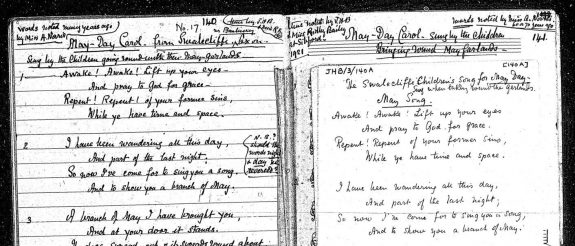

(May Day Song from the Janet Heatley Blunt collection, via the English Folk Dance and Song Society Full English archive.)

(May Day Song from the Janet Heatley Blunt collection, via the English Folk Dance and Song Society Full English archive.)

The only indication that the text has moved from one to another is that they are divided by the lyrics to the folk song May Day Carol:

“I’ve been a-rambling all the night,

And the best part of the day;

And now I am returning back again,

I have brought you a branch of May.”

The central character recalls this song as he waits with the convoy to try and travel to Stonehenge and setup the free festival. It brings back memories of warm May Day celebrations of his youth, when a school-teacher had possibly sought to:

“…soften the lines of the new-build 1960s school building she found herself in charge of, by aligning it with these more archaic and traditional forms of folk art.”

There is a sense at this point of some kind of rural, arcadian, alternative lifestyle that is enjoying a moment of freedom, autonomy and confidence but which will soon have that literally beaten out of it.

I discovered The Fountain in the Forest via a review by Sukhdev Sandhu, in which it is described as:

“An avant-garde take on the pulp crime genre becomes a paean to liberty and a secret history of the 1980s.”

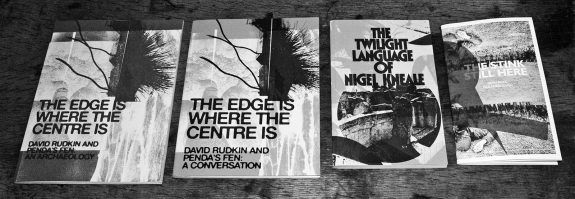

In an interconnected manner to secret histories, Sandhu is one of the key figures behind the publisher Texte und Töne, which has published books/booklets that have included The Stink Still Here, wherein GB84 author David Peace discusses his “occult” (or hidden) history of the UK Miner’s Strike.

The publications are beautifully produced and designed and often explore work that could be seen to sit at the confluence of the undercurrents of folkloric culture and where it meets the spectres of hauntology, including studies of David Rudkin and Alan Clarke’s Penda’s Fen, Nigel Kneales work and the cultural and historical background of the television series The Changes.

As a final aside Tony White has something of a history in subversions/explorations of genre and pulp literature, being the editor of Britpulp! New Fast and Furious Stories from the Literary Underground published in 1999 and which was described as:

“Bursting out of the literary underground, all the writers in this ground-breaking anthology put the emphasis firmly back on gratuitous story-telling and brutal, break-neck plots. Scorching hardcore prose of Stewart Home’s Sex Kick collides with the bitterly romantic confessions of Billy Childish. Nicholas Blincoe’s cool and stylish thriller writing meets the street realism of Victor Headley’s Retropolitan Police, while well-dressed London gangsters fight for page space with the old school skinheads of Richard Allen. Other confirmed authors include Donald Gorgan, Steve Aylett, along with untapped talent from the literary underground.”

He also wrote one of a set of books published in the late 1990s by Attack! Books, alongside the likes of Mark Manning (aka musician Zodiac Mindwarp) and the just mentioned Stewart Home, which in part could be seen to be a then contemporary, transgressive and self-awarely hip updating of the likes of the also just mentioned pulp author Richard Allen, who wrote over 290 novels, including a number of books which focused on late 1960s and 1970s youth subcultures such as skinheads, hippies and bikers.

Elsewhere:

- The Fountain in the Forest at publisher Faber & Faber’s site (including, appropriately enough a crossword competition)

- The Fountain in the Forest novel

- Britpulp! New Fast and Furious Stories from the Literary Underground

- James Moffat / Richard Allen at Wikipedia

- GB84

- In the Morning I’ll be Gone

- Orkney Twilight

- Orkney Twilight at publisher Head of Zeus

- Sukhdev Sandhu’s review of The Fountain in the Forest at The Guardian’s website

Elsewhere at A Year In The Country:

- The Fountain in the Forest – Further Explorations of Hidden History – Part 1: Wanderings 22/52

- In The Morning I’ll Be Gone, Orkney Twilight, GB84 and Edge of Darkness – Hinterland Tales Of Myths, Dark Forces and Hidden Histories – Part 1: Wanderings, Explorations and Signposts 7/52:

- In The Morning I’ll Be Gone, Orkney Twilight, GB84 and Edge of Darkness – Hinterland Tales Of Myths, Dark Forces and Hidden Histories Part 2: Wanderings, Explorations and Signposts 8/52

- David Peace, Texte und Töne, The Stink Still Here and Spectres from Transitional Times – Part 1: Wanderings, Explorations and Signposts 16/52

- David Peace, Texte und Töne, The Stink Still Here and Spectres from Transitional Times – Part 2: Wanderings, Explorations and Signposts 17/52

- Memory of a Free Festival and Other Arcadian Dreams – Part 1: Wanderings, Explorations and Signposts 14/52

- Memory of a Free Festival and Other Arcadian Dreams – Part 2: Wanderings, Explorations and Signposts 15/52