If you’re reading this it’s quite likely you already know who Boards of Canada are but just in case below is some background information on them:

Boards of Canada are a duo of Michael Sandison and Marcus Eoin, who for a considerable period were based in rural Scotland near to the capital city Edinburgh. They are known for creating distinctive and influential often electronic melodic music that incorporates a hazy, nostalgic, distant dream-like and almost hallucinatory atmosphere which utilises vintage synthesisers, samples from 1970s public broadcasting programmes and other previous decades’ media, analogue production methods and aesthetics/flaws such as tape flutter and hip hop inspired breakbeats.

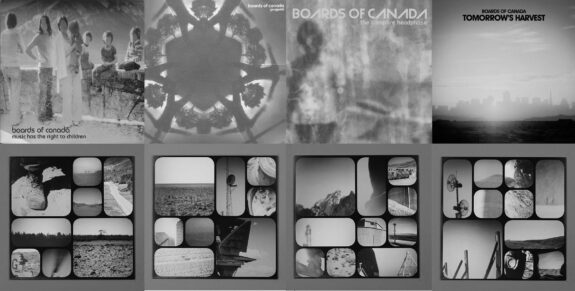

They originally formed in 1986 and have a somewhat enigmatic public persona, in part due to rarely performing live or giving interviews, and when they do so these are often conducted via email, alongside increasing lengths of time between releasing new work (they have released various singles and EPs and the albums Twoism, Boc Maxima, Music Has the Right to Children, Geogaddi, The Campfire Headphase and Tomorrow’s Harvest in 1995, 1996, 1998, 2002, 2005 and 2013 respectively). Adding to this enigmatic air, their work appears to contain cryptic, unexplained, subliminal meanings and messages, either through the use of spoken word samples and/or in a more hidden way in the atmospheres it creates, alongside the use of esoteric methods of production and inspirations:

“They have based a number of… songs on mathematical equations (working out frequencies for melodies that directly correlate to the changing amount of light in one day, for example).” (Quoted from “Breaking Into Heaven”, interview with Boards of Canada by Emma Warren, The Face Volume 3 Number 48, January 2001.)

Their work could be considered to represent a form of midway or transitional point between the likes of instrumental downtempo electronica released by the likes of Wall of Sound and Mo’Wax around the mid-1990s and the hauntological electronica that began to be created and released from around the mid-2000s by Ghost Box Records etc, with the founders of the latter having spoken of how Boards of Canada could be considered an early example of and influence on work that has come to be labelled as hauntological.

One of the relatively few interviews in general, and in person in particular, that Boards of Canada have given was with Rob Young for issue 260 of Wire magazine which was published in October 2005. Looking back both the date of that issue’s publication and also the interviewer now seem to have a particular significance in the lineage of hauntology and where it interconnects with otherly pastoral culture, the themes and expressions of which intersect with Boards of Canada’s work: Rob Young would go on to write the book Electric Eden (2010), which was possibly the first book to extensively explore the fringes and undercurrents of folk and pastoral music and culture and also to intertwine that hauntology; while the mid-2000s was the time when hauntology began to coalesce as a music and cultural form, with for example Ghost Box Records being founded and beginning to release records in 2004; and it was also around this time that the writers Simon Reynolds and Mark Fisher were amongst the first to use the phrase hauntology to describe such work.

There are a number of similarities in terms of recurring inspirations, themes, aesthetics and so on between Boards of Canada’s work and hauntology, with the duo’s work both anticipating and exploring such things in parallel with hauntology. One example of this is how much of hauntology tries to create the sense of a parallel world and how similar could be said of Boards of Canada:

“It’s like we’re inhabiting an alternative, parallel present where maybe someone in the past took a different branch to the way things actually went.” (Quoted from “Boards of the Underground”, interview with Boards of Canada by Richard Southern, Jockey Slut Volume 3 Number 11, December 2000.)

Boards of Canada also share with hauntology a sense and exploration of “the past inside the present” (which is a phrase that is sampled on the “Music is Math” track on the duo’s album Geogaddi) and both often invoke a form of nostalgia without being a straightforward replication of past eras’ music and culture, which can create a comforting sense of familiarity and also an unsettling atmosphere of something unexplained and untoward on the edge of memory and consciousness:

“There are textures in what we try to do… which borrow from certain sounds or eras – even in visual things that we do as well, artwork – to trigger something, almost a cascade. It’s like a memory that someone has – even though it’s artificial, they never even had the memory; it’s just you’re ageing a song. And then people feel, is that something familiar I knew from years ago?” (Quoted from “Protect and Survive”, interview with Boards of Canada by Rob Young, The Wire issue 260, October 2005).

Boards of Canada also share with hauntology an interest in certain strands of 1970s television and an accompanying hazily skewed or eldritch take on educationalism, public information films, government organisations and so on, with the duo taking their name from a Canadian government organisation called the National Film Board of Canada which is dedicated to distributing educational film, the output of which they watched when young after their families emigrated for a time to Canada. They have spoken in interviews about how the aesthetic of their work was influenced by viewing such films, in particular the characteristics and flaws of their era’s media (such as tape flutter etc) and this interconnects with Boards of Canada and hauntology drawing from a wider sphere of older educational and children’s television and its electronic soundtracks:

“Among the many common concerns [between Boards of Canada and Ghost Box artists such as The Focus Group and the Advisory circle]… a nostalgic fascination for television stands out as the major connection. During the ’70s especially, children’s TV programming in the UK featured a peculiar preponderance of ghost stories, tales of the uncanny, and apocalyptic scenarios (like “The Changes”, in which the populace rises up and destroys all technology). In between this creepy fare, young eyes were regularly assaulted by Public Information Films, a genre of [government-commissioned] short British programs made for TV broadcast and ostensibly designed to educate and advise [but which often contained suprisingly unsettling atmospheres and themes]… The unsettling content of all this vintage kids-oriented TV seeped into the brains of Sandison and Eoin at a vulnerable age. But what seems to have lingered even more insidiously in the memory of BoC, and the hauntologists that came after them, is the music. For many Brit kids, the sound effects and incidental motifs made for these programs by outfits like the BBC Radiophonic Workshop were their first exposure to abstract electronic sounds. Speaking in 1998, Sandison claimed that these theme tunes and soundtracks were ‘a stronger influence than modern music, or any other music that we listened to back then. Like it or not, they’re the tunes that keep going around in our heads.'” (Quoted from “Why Boards of Canada’s Music Has the Right to Children Is the Greatest Psychedelic Album of the ’90s”, Simon Reynolds, pitchfork.com, 3rd April 2018.)

There is at times a form of melancholia present in both Boards of Canada’s work and hauntology:

“[Hauntological music and culture] draws from and examines a sense of loss, yearning or nostalgia for a post-war utopian, progressive, modernist future that was never quite reached, which is often accompanied by a sense of lingering Cold War dread.” (Quoted from A Year In The Country: Straying From The Pathways, 2018.)

Connected to which in the above article Reynolds writes:

“Another hauntology theme that Boards of Canada anticipated is the notion of the lost future. Again, this tends to be identified most with the ’70s and that decade’s queasy ambivalence about runaway technological change: on the one hand, there was still a lingering post-World War II optimism abroad, but it was increasingly contaminated with paranoid anxiety about ecological catastrophe and the rise of a surveillance state. ‘Looking back at TV and film from that decade, a lot of what you see was pretty dark,’ says Sandison. By the early ’90s, when BoC were finding their identity, ‘all the sounds and pictures from back then seemed like a kind of partially-remembered nightmare.’” (Quoted from “Why Boards of Canada’s Music…”, as above.)

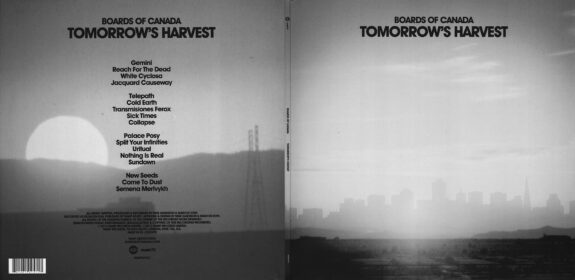

Boards of Canada’s 2013 album Tomorrow’s Harvest contains a hidden, layered and possibly even bleak connection with and evocation of the Cold War and dystopian futures. The album’s title was inspired by a US website which sells survivalist supplies intended for use in a crisis scenario such as dried foods, solar power equipment and so on, while the front cover image of a sun bleached city skyscape off in the distance doesn’t seem to so much represent a view of the vitality of sunlight but rather has a queasy unsettling air:

“The cover appears to be a photo of the San Francisco skyline, shot from the vantage point of Alameda Naval Air Station, a now defunct military base operational during the cold war.” (Quoted from “Boards of Canada: ‘We’ve become a lot more nihilistic over the years'”, Louis Pattison, theguardian.com, 6th June 2013.)

When, in the above interview with Louis Pattison, Boards of Canada were asked if this image and its location were a coincidence or did it point towards themes and concepts in the record, Eoin replied:

“Yeah, definitely – of course that’s an ingredient of the theme on this record. In fact if you look again at the San Francisco skyline on the cover it’s actually a ghost of the city. You’re looking straight through it.” (Quoted from “Boards of Canada…”, as above.)

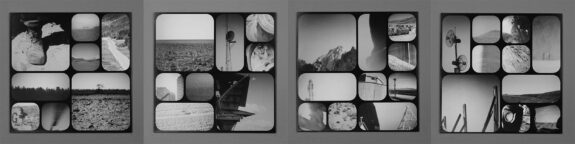

The album booklet and insert artwork which accompanied the release of Tomorrow’s Harvest appears to futher explore and infer such dystopic and unsettling themes and feature grids of often indistinct and cropped photographs that also often incorporate the scanlines and/or pixel dot patterns of older cathode ray televisions and monitors. They are unaccompanied by any explanatory text and while they were presumedly created for the album there is something about them which makes them appear as though they are possibly unsanctioned stills from some form of official surveillance.

The images include a number of communications masts and infrastructure that also unstatedly infers a sense of some indefinable past Cold War paranoia infused decade, alongside the likes of a potentially broken down car, featureless silhouettes of people off in the distance, brutalist concrete architecture, arid desert and a forest or crops which has been decimated by some unknown event. These sit alongside occasional views of still healthy seeming natural landscapes, which only seem to highlight the desolate and unsettling nature of the other images and to leave the viewer with a sense that they may well be isolated last pockets of such things after a time of catastrophe.

Exploring the flipside and undercurrents of the pastoral and folk music is something of a recurring theme in Boards of Canada’s work and in interviews they have included the British psychedelic folk band The Incredible String Band, that were formed in 1966, as one of their “likes” or influences. Such elements were given more overt expression on the Campfire Headphase album, which included more organic instrumentation such as acoustic guitars, albeit still heavily treated, alongside more conventional song structures. The resulting work in part appears to represent an hallucinatory time stretched event experienced around a campfire and at times is not dissimilar to listening to a group of friends jamming around the embers of the fire late into the night, although as filtered through the half-memory of a distant dream rather than being a straightforward recording or recollection.

Such pastoral elements could be considered to connect with the way in which and location that Boards of Canada make their music. For much of the time when working as Boards of Canada they have been based, as mentioned at the start of the post, in rural Scotland near to the capital city of Edinburgh and at a remove from wider and/or urban trends and influences:

“[Eoin spoke of how ] ‘This whole project has come about with us living on the outskirts of Edinburgh… and for the last two decades we’ve been working on it from here, and we’ve had no reason to want to relocate to the city or to the south or anything, it’s as simple as that. In fact, we actually find to some extent this so-called hermetic bubble that we live in is actually making it a lot easier for us to do our thing and not feel any urge to make it DJ friendly, or make it work for a certain social or club environment.'”

Their music’s creation of a self-contained seeming world and its distinctive character can also be seen as, in part, a reflection of that “hermetic bubble” and a reaction against the city and urban aesthetics:

“They stand for… above all, a rural ideal completely opposite to the fast-paced urban excitement that has powered pop music for nearly 50 years.” (Quoted from “Breaking Into Heaven”, as above.)

Another distinctive aspect of Boards of Canada’s work that it shares with and anticipated in hauntology is the use of previous eras’ synthesised sounds alongside, as referred to at the start of this post, audio aesthetics which recall older analogue recording equipment and media, such as tape wobble, vinyl imperfections etc:

“[In hauntology the] use and foregrounding of recording medium noise and imperfections, such as the crackle and hiss of vinyl, tape wobble and so on calls attention to the decaying nature of older analogue mediums and… can be used to create a sense of time out of joint and edge memories of previous eras.” (Quoted from A Year In The Country…, as above.)

At times such elements were present in other downbeat and trip hop related work from around the mid to later 1990s:

“Tricky, Massive Attack and Portishead’s [used vinyl crackling] in order to create particular atmospheres and effects… it is not clear whether it was actually present in the original vinyl records which they sampled or added afterwards. In DJ Shadow’s work, the use of [vinyl] crackle in his recordings from a similar period is possibly more likely to have been both an inherent part of the way his records from the 1990s were created as soundscape collages built from old ‘found’ records rather than, as in Tricky, Massive Attack and Portishead’s case, vocal-led songs which utilised samples. In this respect, it also serves as a reminder of this recording process, an acknowledgment and homage to the layers of recording history from which his tracks were built and its reconfigured spectral echoes… In Tricky, Portishead and DJ Shadow’s work from the 1990s [such aesthetics instill] a sense, at points, of the music belonging to a time the listener cannot quite place; one that is both contemporary in style and its production techniques but which also seems sometimes to exist in an atemporal timeline of its own.” (Quoted from A Year In The Country…, as above.)

As commented on by Simon Reynolds in the above-mentioned article on Music Has the Right to Children, the creation of music which exists in a time of its own has long been present in Boards of Canada’ work, and he writes that their intention “was to create a haunted haven outside the onward flow of Time”.

Which seems like something of a suitable (and somewhat Sapphire & Steel-esque) point on which to end this post.

Elsewhere:

- Boards of Canada’s Twitter page

- Boards of Canada at Warp Records

- Boards of Canada at Bleep’s online shop

- Boards of Canada unofficial wiki information site

- Simon Reynold’s “Why Boards of Canada’s Music Has the Right to Children Is the Greatest Psychedelic Album of the ’90s” article at Pitchfork

- Rob Young’s Electric Eden site

Elsewhere at A Year In The Country:

- Boards Of Canada – Tomorrows Harvest; Stuck At The Starting Post / Tumbled From A Future Phase IV

- Boards of Canada, The Delaware Road, Mo’Wax, UNKLE, DJ Shadow, Tricky, Portishead, Massive Attack, Moon Wiring Club, DJ Food, Belbury Poly, The Memory Band, Grantby, the BBC Radiophonic Workshop and Andrea Parker – Universe Creation and Spectral Lines in the Cultural Landscape

- Electric Eden – Unearthing Britain’s Visionary Music – Folk Vs Pop, Less Harvested Cultural Landscapes and Acts of Enclosure, Old and New

- A Definition of Hauntology – Its Recurring Themes and its Confluence and Intertwining with Otherly Folk

- Spectres vs Retro – Simon Reynolds’ Haunted Audio Article in Wire Magazine

- Ghost Box Records – Parallel Worlds, Conjuring Spectral Memories, Magic Old and New and Slipstream Trips to the Panda Pops Disco