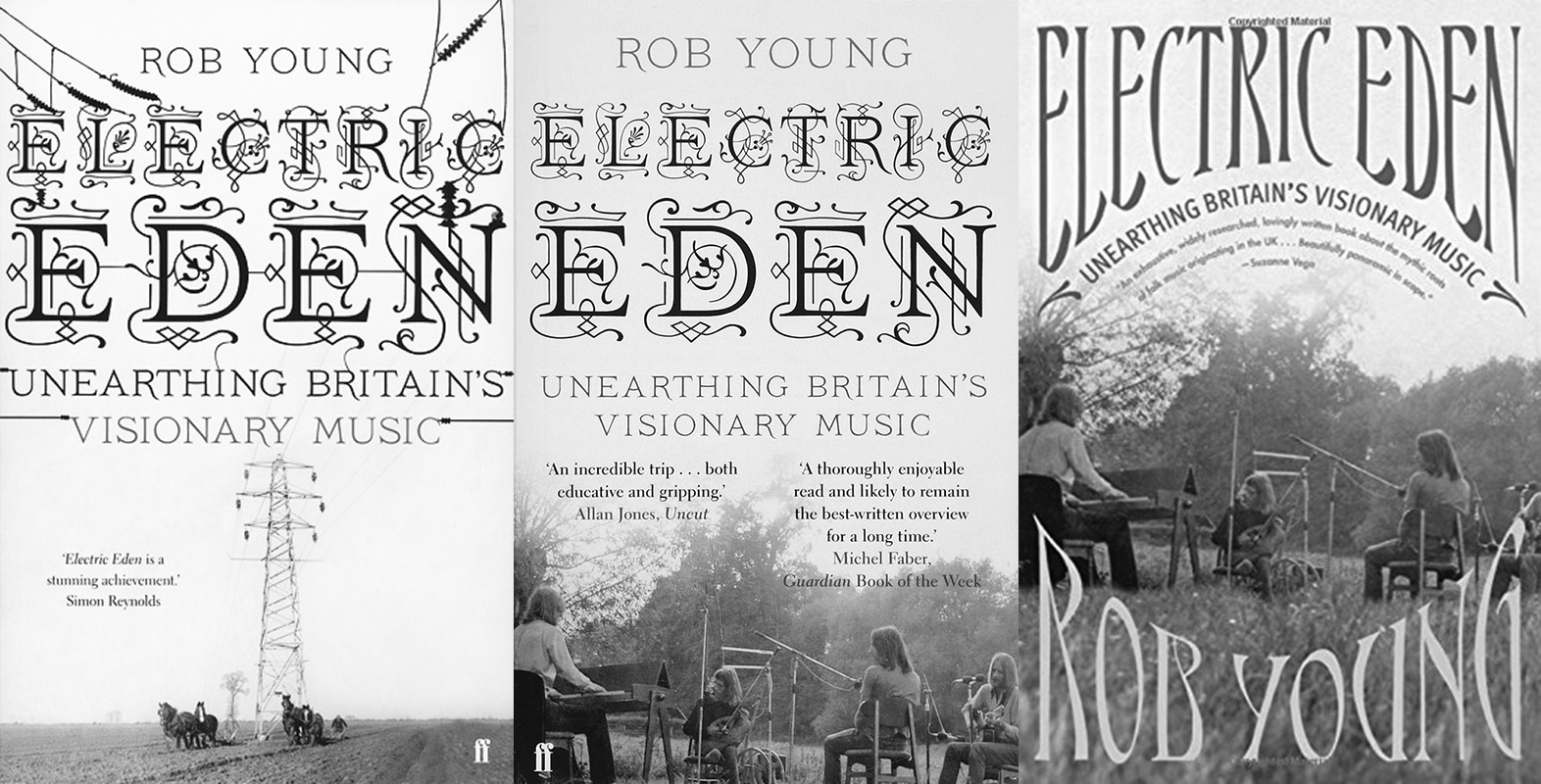

Electric Eden: Unearthing Britain’s Visionary Music, the 2010 book by Rob Young, served as an ongoing reference for much of the earlier years of A Year In The Country.

It is an epic tome of a book which, in simple terms, is a journey through British folk and pastoral music and related culture from its roots to the modern day, but instead of serving as a straightforward documenting of such things, is more an exploration of its undercurrents, of at times semi-hidden or overlooked cultural history and its interconnected strands.

The book explores folk revivalist collectors such as Cecil Sharp, the social idealism of William Morris and Ewan MacColl, the late 1960s/early 1970s folk rock of the likes of Fairport Convention and Pentangle, the acid or more experimental folk of Comus and Forest, the iconic 1973 folk horror film The Wicker Man and related occult folklore, contemporary esoterically interconnected hauntological practitioners such as Ghost Box Records, the pastoral tinged work of pop music explorers Kate Bush, David Sylvian and Talk Talk and pastoral speculative/science fiction.

There is a sense within the book of folk and related culture seeming to point towards an otherly Britain: an imagined Albion of hidden histories and sometimes arcane knowledge, wherein there is still the space or possibility to sidestep some of the more ubiquitous, dominant and monotheistic tendencies of modern- day culture, beliefs and systems.

The later chapter in the book, “Towards the Unknown Region”, explores the more overtly undercurrent or semi-hidden areas of pastoral-orientated work and the just mentioned interconnected realms of hauntology. In this chapter Rob Young recalls a time when he attended a Ghost Box Records event and he relates a sense of the excitement and envelopment that stepping into a separate seeming created world or reality via cultural forms, scenes and events can provide, even if only for the duration of a record playing, or an evening or two.

He comments that at such times the creators and participants engage in a form of consensual sensory hallucination, which is a succinct and evocative description of the sense of giving yourself up to otherworldly cultures and its stories. Connected to which the book contains a number of phrases which deftly and briefly capture cultural activities, including “imaginative time travel”.

This is used to describe a personal and cultural form of exploring and taking inspiration from different historical periods, possibly mixing them with contemporary techniques and modes to produce work that creates new forms rather than being strictly recreations of times past.

For example, work within folk culture such as late 1960s/early- to-mid 1970s folk rock and acid/psych folk, where the participants at times seemed to actively attempt to will into existence musical, aesthetic and social forms that drew from the past but in a refracted and reinterpreted manner and which existed in a never- never land of their own creation.

The book doesn’t contain a judgemental distinguishing between what could be considered authentic folk that has been handed down in an oral or traditional manner over the centuries and the latter-day exoticism of contemporary folklore-influenced work such as the above-mentioned The Wicker Man; all such strands could be seen as authentic, work has to spring from somewhere and it could be considered that it is the intention and effect rather than age and historical traceability that implies whether it is the “real” thing or not.

In Electric Eden and related writing and interviews Rob Young has also considered the roots of the words and concepts of folk and pop.

The phrase “folk music” can seem a little confusing initially. There is a tendency to think of folk as meaning “from the people”, as in all of the folk of a land, which leads to the question, how can music that seems to have often, today at least, a relatively limited appeal therefore be called folk music? How can it be of the people if it is not widely popular? And it is definitely not pop music.

Rob Young has put forward the case that rather than referring to a sense of all the people of the land, folk music is the music of the “volk”, derived from the Germanic/Teutonic wald – the wild wood – whereas the word “pop” (i.e., popular music) comes from the Latin populous, which refers more to the larger populations of cities etc.

He talks of how pop culture derives from centrally controlled, regimented urban communities (Roman urban populi) which were entertained, appeased and distracted by mass spectacles such as gladiatorial entertainment and comedic dramas: that pop is a culture that belongs to or springs from imperial socialisation, institutionalised religion, related consensus and commerce.

In contrast, folk is much older than pop, originating from the wild wood and a culture where peasants, vagrants and villagers bore song from those woods, the forest, the barbaric heath – societies which were sometimes savage, often ad hoc, structured in a less hierarchical manner, pre-Christian and where rituals endured and perplexed their heirs.

The Romans made efforts to clear away these potentially problematic, less governable areas but Rob Young notes that they still survive in English place names that end with “wald”, “wold” or “weald”.

As cultural forms and phrases therefore, one comes from the city, one from elsewhere out amongst the land.

In many ways, the story of folk music, culture and folklore is in part one that tells of the differences and separateness of culture from the city vs the wald or the populi vs volk or more literally folk vs pop. Which brings things round to The Wombles and what happens when folk meets or tries to become pop.

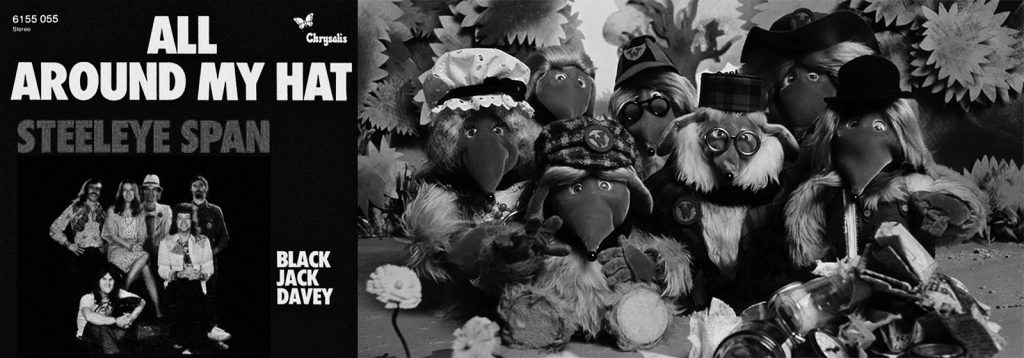

What appeared to happen in the mid-1970s is that music arrived at a point where one of folk rock’s more popular bands Steeleye Span had a hit single with their version of the traditional folk song “All Around My Hat”, which reached number five in the UK singles charts in 1975.

The single was produced by Mike Batt, who also oversaw records for the novelty pop band The Wombles: these were a musical offshoot of an animated children’s television series originally broadcast from 1973-1975 where furry, pointy-nosed creatures who live in burrows on Wimbledon Common spend their time recycling rubbish in creative ways.

“All Around My Hat” is folk that has wandered quite a way from its roots and seems intrinsically to be nearer to pop, a kind of glam romp with folk trappings. Which is not to dismiss this version as it is a rather catchy and full of life interpretation, with the song and its video capturing a certain point in time and period nuances of British cultural history: of pop music and culture that was not yet overly-styled, honed and scientifically marketed and that in its own particular way is still from a less tamed cultural landscape.

This is one of the themes of Electric Eden; a sense of a taming of the cultural and at points literal landscape of what Rob Young presents as music and culture of a utopian or visionary nature that draws from the land and folk culture.

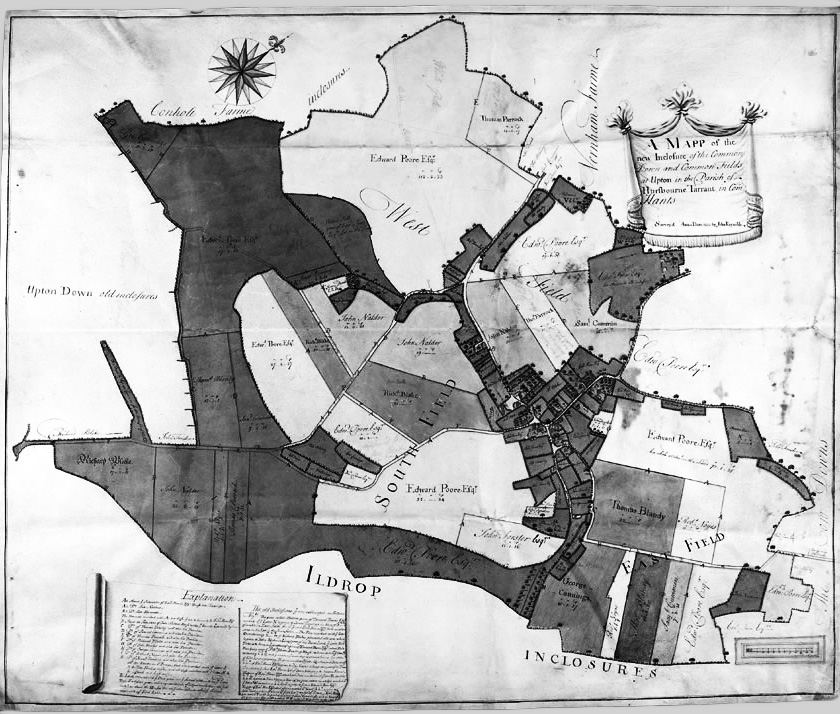

He has discussed the connection between such areas of work and culture and how there is a connection to historic acts of land enclosure and clearance; the way in which from around 1760 onwards in Britain common land was put into private ownership by government Inclosure Acts, forcing agricultural workers towards the newly expanding cities and factories and how this displacement could be one of the roots of the British empathy with the countryside, with such as songs or texts from the world before this change having come to be revered as they seem to represent or connect to a pre-industrial “Fall” golden age.

It could be said that Inclosure Acts are not a purely historical practice.

In recent years a proportion of the population have found themselves increasingly priced out of certain areas of the country; the cost of putting a roof over your head (in terms of the ever upward path of rental and property prices), of keeping the lights on and the wolves from the door seems to quietly, gradually be removing a certain less material wealth funded or directed way of life out of cities and in particular city centres and the capital city of Britain.

This could be considered to be a form of enclosure; a more subtly enacted mirror image of the earlier 18th century version.

In recent times this has happened in part through decisions to not take or delay particular actions as well as the ending of acts of Parliamentary regulation (removing, watering down, delaying or refusing to implement statutory rent control or regulation for example), with the result that the “common people” are being removed from the inner cities rather than forced into them.

Also, more physical, bricks and mortar-related acts of enclosure have been accompanied by an undercutting of the economic infrastructure for creative work, whereby large-scale transnational corporations effectively gain access to a huge library of content and very low paid or unpaid workers for their often advertising orientated delivery systems and hardware, often at minuscule cost, such as with online music streaming or even for free in the case of social media.

This has often been done under the guise of ease of distribution, expression and choice, which while it can be useful in the sense of “getting your work out there without being massively bankrolled”, the end result of which is often a technological or creative form of enclosure.

This in turn often leaves the ongoing viability, in terms of keeping those aforementioned lights on and cupboards full, of such work largely in the hands once again of the few, of those selected and patronised by high-end conglomerates and/or those who are privately or institutionally funded. In this system a small elite of, for example, globally ubiquitous popstars are able to reap huge rewards and to a lesser degree some of the “influencer” stars of social media have also benefited financially but this seems to largely have been at the (financial) cost of much of what could be considered to be the working and middle classes of creative culture.

Connected to this the space needed for the creation of more wayward forms of culture has become a harder path to follow.

There seems to have been an element of choice being taken away and of things reverting to older forms of wealth and class division, resulting in a form of social and economic clearing out and exclusion, a removal of access for those of lesser financial means to the clustering and critical mass of population that is sometimes required within cities for cultural forms to develop and take hold.

At the same time rural, as opposed to urban, environments do not tend to have such a publicly displayed saturation or overload of culture and input, although this can still be present in a less visible sense to a degree as many homes now contain multiple digital devices that via online access can allow or enable vaststreams of cultural information and input.

Out in the country you rarely see billboards, there are fewer shop windows, generally fewer cultural events and venues, flyposters are relatively rare, the headlines and covers of newspapers and periodicals cannot catch your eye from every corner and there is also often relatively less CCTV surveillance and recording in country towns and villages compared to cities.

Accompanying which, at times, some of the inherent character or spirit of folk music, alongside certain areas of hauntology and pastoral/subterranean ambient/electronic music, their rhythms, cadences and the stories they tell can seemingly make more sense beyond youth and out amongst the fields.

It is important to point out that all cities and compact urban population environments are not inherently evil, nor that the countryside and country living is all green grassed idyll, nor that pastoral and folk culture is part of some dichotomous good/bad pathway with urban/pop culture.

It is possible that we know the stories of pop and its associated alternative or fringe culture a little too well, as they have been told, retold and used too often by the mainstream and non- mainstream media, until for many people their stories no longer carry the meanings and connections they once did.

Since the advent and popularity of more urban-based pop music/culture, what has been called folk music and culture has only periodically and/or nichely been popular or considered acceptable for wider marketing and consumption, for example at times such as the high summer of folk rock in the late 1960 to early or mid 1970s, or the interest in freak folk in the earlier-to- mid 2000s.

Interconnected with which the direct sunlight of media and mass attention can be a potentially double-edged sword for subcultures, as at times it does not allow cultural forms the space they need to grow and develop fully and leads to culture being plucked and harvested too early.

As Jeanette Leech says in her introduction to the 2012 Weirdlore compilation album of underground and exploratory folk:

“…when light is not on a garden, many plants will wither. But others won’t. They will grow in crazy, warped, hardy new strains. It’s time to feed from the soil instead of the sunlight.”

Within the undercurrents of folk and wyrd culture there is a sense of it having been left alone to a degree; it is a cultural form which has been allowed to gain nourishment from the earth rather than the brighter rays of public attention.

As is suggested by Rob Young in Electric Eden, the space around such work feels less regulated. There is still some space to move and dream around such things, which may be less so in other areas of culture; you can possibly (or hopefully) still walk these “wild woods” a little more freely.”