Well, this post may initially seem like something of a “cuckoo in the nest” at A Year In The Country but there are lines and points of connection with the likes of Mo’Wax, UNKLE, Tricky, Massive Attack and the spectral hauntological, otherly interests that are generally found around these parts, including The Delaware Road events.

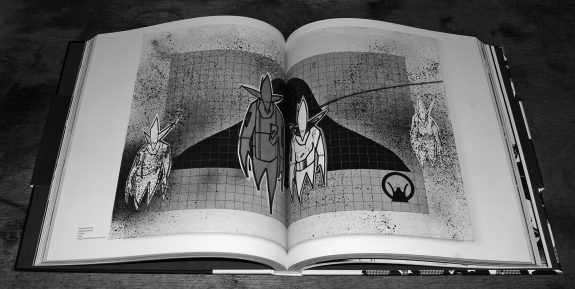

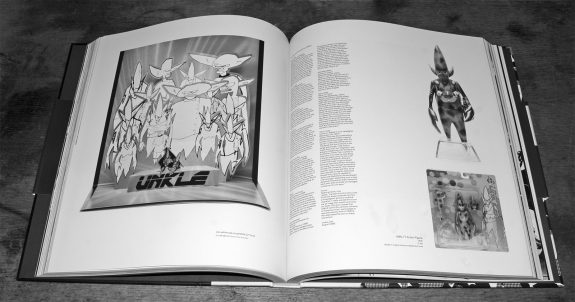

James Lavelle, the founder of record label Mo’Wax and the band UNKLE has talked about “creating your own universe”, something which he has often done in his own work with say UNKLE’s Psyence Fiction album from 1998 seeming to belong to and spring from a wide-ranging and almost epically cinematic created and self-contained world of distinctive illustrations, multiple variations of bespoke packaging, physical artifacts such as toys and conceptual underpinning.

That sense of creating your own universe is essentially what often happens within hauntological and the further reaches of folk work; whether that be the parallel world created by Ghost Box Records or the form of “imaginative time travel” (to quote Rob Young from his book Electric Eden) that was carried out by folk music and culture explorers in the 1970s when they appeared to be attempting to create and/or drawing from an imagined historical and cultural folkloric landscape that never existed in the “real” world.

As I have referred to at A Year In The Country before, the distance from the abstract instrumental hip hop/electronica or “trip hop” for which Mo’Wax is particularly known is not all that far removed from and has various lines of connection with some hauntological orientated music.

(And as an aside I would highly recommend the documentary The Man From Mo’Wax that focuses on the work of James Lavelle, which even if you are not directly interested in the likes of Mo’Wax, UNKLE, DJ Shadow etc is still a fascinating piece of film making in the way that it captures the story of a particular slice of culture/creating your own universe and one of its main instigators.)

Hauntology forebears Boards of Canada often utilise instrumental electronic breaks and beats that are not that dissimilar in terms of their downbeat, more abstract nature from those that may have been found on a Mo’Wax release in the 1990s and Ghost Box Records artist Belbury Poly collaborated on the 10″ Further Navigations, an “exploration of the ancient Harrow Way, the ‘lost’ road of Southern England”, with The Memory Band and Grantby aka Dan Grigson, the latter of which had a track on Mo’Wax compilation Headz 2 released in 1996.

(Further interconnecting such things Stephen Cracknell of The Memory Band also worked with Dan Grigson in a similar period in the 1990s, including collaborating as Barcode on the track Love Anybody, which was included on the 1996 album Cup of Tea Records – A Compilation, a release by a label which at times explored not dissimilar trip hop-esque areas of music as Mo’Wax and which was described as releasing “slo-mo beat excursions and weirdelic sound collages”.)

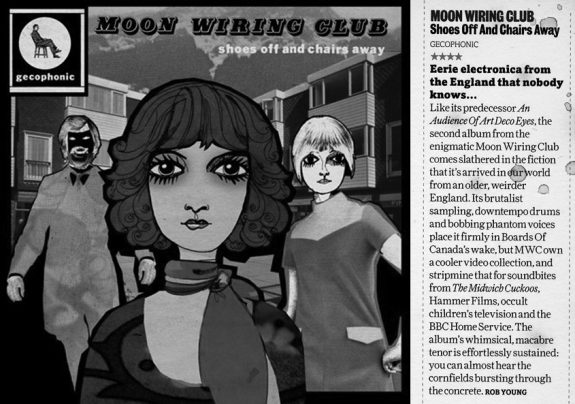

Alongside which if looked at in a more purely musical/audio basis rather than as part of a hauntological cultural landscape then the whimsical spectral work of Moon Wiring Club and its use of downbeat electronica, beats and samples could well have been found on a label such as Mo’Wax contemporary and also trip hop-esque/abstract electronica label Wall of Sound in the 1990s.

If you were to replace the 1970s British children’s television and archival broadcast footage used in Moon Wiring Club’s samples and videos with say the underground hip hop sampling and reference points of some Mo’Wax and Wall of Sound related work then they share a fair amount of musical similarities, as Moon Wiring Club’s work also does with Boards of Canada:

“It’s brutalist sampling, downtempo drums and bobbing phantom voices place it firmly in Boards of Canada’s wake.” (Rob Young writing in a review of Moon Wiring Club’s Shoes Off And Chairs Away album in Uncut magazine.)

While former Mo’Wax released artist Andrea Parker, alongside Daz Quayle, has gone on to produce the Private Dreams and Public Nightmares album (2011) which reinterpreted the work of electronic music pioneer, BBC Radiophonic Workshop member and hauntological point of reference and inspiration Daphne Oram.

Lines of connection could be drawn from the likes of Oram’s pioneering explorations in electronic music and much of the electronic based music mentioned in this post – without her work and that by the likes of Delia Derbyshire (and possibly the futurist electronic pop of Kraftwerk) this post and some of the music and culture it discusses may well be rather different.

To further draw lines of connection between this (rather) loose cultural landscape, in 2019 Andrea Parker is also to be one of the performers at The Delware Road: Ritual and Resistance two-day festival organised by the Buried Treasure record label, which takes place inside a military base near Stonehenge, an event at which “artists will perform work inspired by landscape, myth, broadcast propaganda and the transformative nature of sound”.

The line-up for the festival draws from what could be called the confluence between otherly pastoral/hauntological work and also includes a number of performers etc who work in such areas including Paul Watson, Front & Follow, Kemper Norton, Sarah Angliss, Simon James, Revbjelde, Castles in Space, The Twelve Hour Foundation, Concretism, Polypores, Alison Cotton, Ian Helliwell and Radionics Radio.

And again further interconnecting such things The Delaware Road draws its name from an actual road in London where the BBC’s Radiophonic Workshop was originally situated…

DJ Food (aka Strictly Kev) is also in the event’s line up, which provides further lines of interconnection with some of the themes and work mentioned in this post as some of the music released as DJ Food at times explores not dissimilar territory as DJ Shadow did on his Mo’Wax released records in the 1990s

(Which to loosely describe it could be called “left-field beats, breaks and crate digging sample based, abstract often instrumental hip hop cut-n-paste soundscaping” and in DJ Food’s case on the likes of the Kaleidoscope album released in 2000 this is sometimes spliced with a playful, humorous aspect that samples and/or recreates period Beat era and noir themes and styles.)

The DJ Food records have generally been released on the label Ninja Tune, which was founded in 1990 by some of the collaborators who have worked on the DJ Food releases and in terms of aesthetic and musical styles – abstract instrumental hip hop etc – it has released music which has at times explored some similar cultural territory as Mo’Wax releases did in the 1990s.

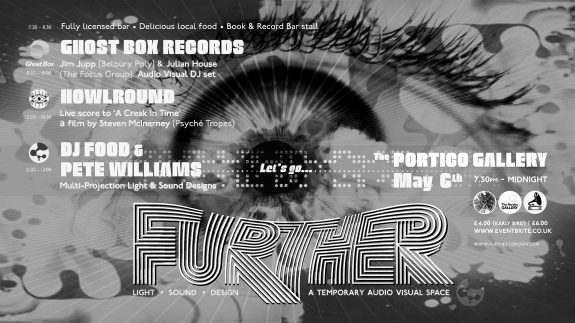

Alongside appearing at a previous Delware Road event, in recent years Strictly Kev, working as DJ Food, has also co-created the Further events in London, which have featured performances and audio-visual DJ sets from some of those who work in similar hauntological cultural territories as The Delaware Road: Ritual and Resistance event and/or are appearing at it, including Howlround, Ghost Box Records and Simon James of Black Channels. Further interconnecting things as DJ Food he has also organised and performed at the O is for Orange events, the second of which was a Boards of Canada influenced live event featuring a montage of music, found audio and psychedelic imagery.

All of which brings me back to “trip hop”…

Trip hop has become something of a dirty or uncool genre description that is often used fairly narrowly to refer to music that came after Portishead’s first album Dummy in 1994 and as a description it sometimes refers to music which possibly overly narrowly utilised Portishead’s template of downbeat hip hop drum beats and smoky female vocals. Here I use it as a shorthand to indicate a wider and loose cultural grouping and set of atmospheres that included the likes of the instrumental abstract hip hop beats of for example some Mo’Wax 1990s releases (possibly DJ Shadow – although I would say his Endtroducing album released in 1996 and his related work from that period exists more in a world unto itself, more on such things in a moment), the haunted noir of Portishead, the at times claustrophobic intensity and tinges of darkness of Massive Attack and the fractured paranoid wordscape introspections of Tricky.

If revisited now the 1990s work of Massive Attack and Tricky sound in part like spectral British reinterpretations and reinventions of hip hop and rap culture; not so much a hauntological-esque misremembering but possibly work created as though it could only access its source material via a distant, out of tune, fading in and out shortwave radio or via darkened dreamscapes.

In terms of existing in and creating your own universe, Tricky’s more recent albums such as False Idols and Ununiform also seem like something of a homecoming for him – he appears to have become more accepting of the possibility that his work exists in its own cultural space and the albums have a focus that in part draws from and references his own legacy and its self-contained nature, with some tracks directly referencing his earlier music in a self-sampling or almost Part 2 of an ongoing story manner.

To a degree in the 1990s Tricky was marketed as a pop-star and had Top 20 hits in the UK etc but his appearance as a guest of pop mega-star Beyonce at the large-scale music festival Glastonbury in 2011 provides a striking example of just how far removed he is from the mainstream pop pantheon; he seems like a very alien or “other” presence in amongst the twirling backing dancers and Beyonce’s pop-grinding.

Portishead’s work in the 1990s also to a degree draws from a distant view of hip hop musically but then combined it with an atmosphere that seemed to conjure an imaginary smoky late night noirish world, further echoing American source material (i.e. noir film, literature etc culture) but rather than being a retro retreading it created a new world all of its own – something of a recurring theme in this post it would appear.

Aesthetically connecting such work to hauntology, the use of spectral aesthetics can also be found in Massive Attack’s more recent Fantom / Fantom 2 apps, whereby their music can be remixed by moving the device and its camera in order to cause the source audio to be manipulated into its own fractured spectres and creating quietly unsettling, shadowed and trail filled imagery of the app’s user.

Further points of connection could be made due to both some hauntological work and tracks by Portishead, Tricky, Massive Attack and DJ Shadow that were produced in the 1990s noticeably utilising the sound of vinyl crackle, which connects with what writer and academic Mark Fisher described in his book Ghosts of My Life as being “perhaps the principal sonic signature of hauntology”:

“William Basinki, the Ghost Box label, The Caretaker, Burial Mordant Music, Philip Jeck, amongst others… (These) artists that came to be labelled hauntological were suffused with an overwhelming melancholy; and they were preoccupied with the way in which technology materialised memory – hence a fascination with television, vinyl records, audiotape, and with the sounds of these technologies breaking down.”

While some of the music produced in the 1990s by DJ Shadow, Tricky, Portishead and Massive Attack may have a melancholic air and as previously mentioned at times be accompanied by a form of paranoid introspection, this appeared to draw more from a consideration of personal feelings and/or in Portishead’s case an associated noirish almost fatalistic seeming atmosphere, whereas often in hauntological labelled work the sense of melancholia can be seen in part as taking inspiration from and being an expression of a personal-societal sense of lost progressive futures.

Rather than having such an overt philosophical underpinning, Tricky, Massive Attack and Portishead’s use of vinyl crackling may be considered more as a result of aesthetic choices in order to create particular atmospheres and effects and it is not clear whether it was present in the vinyl records which they sampled or added afterwards. In DJ Shadow’s work the use of crackle in his recordings from a similar period is possibly more likely to have been both an inherent part of the way his records were created as soundscape collages built from old “found” records rather than, as in Tricky, Massive Attack and Portishead’s case, vocal lead songs which utilised samples and also serves as a reminder of this recording process, an acknowledgment and homage to the layers of recording history from which his tracks were built and its reconfigured spectral echoes.

As with some hauntological work this use of vinyl crackle and referencing of the physicality of older analogue recording methods, as also commented on in Ghosts of My Life in reference to hauntologically labelled music, can often appear to “make us aware that we are listening to a time that is out of joint”. It instills a sense of the music belonging to a time the listener cannot quite place; one that was both contemporary in style and its production techniques but which also seemed to exist in an atemporal timeline of its own.

Elsewhere:

- Private Dreams And Public Nightmares – Daphne Oram Reworked and Re-Interpreted by Andrea Parker and Daz Quayle

- The Delaware Road – main website

- The Delaware Road: Ritual & Resistance – tickets at fixr

- The Delaware Road: Ritual & Resistance – tickets at Bandcamp

- Moon Wiring Club / Blank Workshop

- Massive Attack’s Fantom

- Mo’Wax Urban Archaeology: 21 Years of Mo’Wax Recordings

– a rather beautiful book and highly recommended…

- …as is The Man From Mo’Wax documentary

- Ghost Box Records

- Mordant Music

- Mark Fisher’s Ghosts of My Life at Zero Books

- Mark Fisher’s Ghosts of My Life

- DJ Food’s “online scrapbook” site…

- …and more specifically, the A Year In The Country: Wandering Through Spectral Fields book at DJ Food’s site here…

- …and here.

- The Further Navigations 10″ at Static Caravan Recordings

Elsewhere at A Year In The Country:

- The Delaware Road at Kelvedon Hatch

- The Quietened Bunker, Waiting for the End of the World, Subterranea Britannica, Bunker Archaeology and The Delaware Road – Ghosts, Havens and Curious Repurposings Beneath our Feet

- Dropping Science: From Endtroducing to The Electronique Void Via Haunted Tea Rooms And Pans People

- 14 tracks – “Hauntology: A peculiar sonic fiction”

- Central Office Of Information + Mordant Music = MisinforMation

- Mark Fisher’s Ghosts Of My Life and a very particular mourning and melancholia for a future’s past…

- The Following Of Ghosts – File Under Psychogeographic / Hauntological Stocking Fillers

- A return to OST… from teacake time to sacred relics…

- The ether ephemera of Mr Ian Hodgson and wandering from village green preservation to confusing English electronic music…

- Further – A Temporary Audio Visual Space

- Further and Audio Visual Explorations