Another slowly growing mini-collection on the shelves of A Year In The Country – this time it’s focused on and around that much-loved saggy old cloth cat Bagpuss.

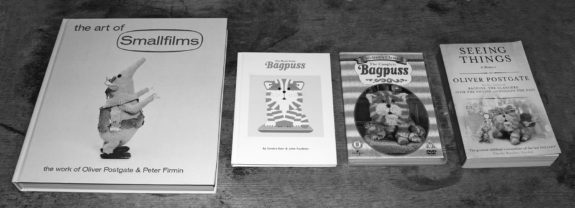

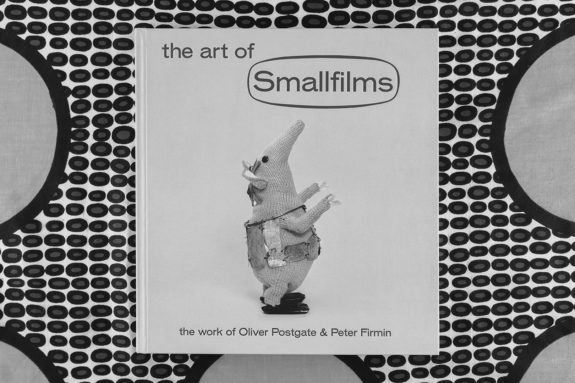

In this mini-collection there’s the 2005 DVD release of the series (surely it’s time for a Blu-ray upgrade?), a slightly battered copy of Oliver Postgate’s Seeing Things memoir, the 2018 Earth Records release of The Music From Bagpuss and Jonny Trunk and Richard Embray’s The Art of Small Films book.

If you’re reading this I expect you already know about Bagpuss but just in case below is a brief overview of the series:

Bagpuss is a children’s television animated series made by Oliver Postgate and Peter Firmin’s Smallfilms and was first broadcast on British television in 1974. Set in some unnamed past era, probably early twentieth century, it is based around a shop owned by a young girl called Emily, in which nothing was sold but rather she displayed lost and broken things in order that their owners would hopefully discover and collect them.

Each episode would begin with a sepia tinted sequence that explained about Emily, the shop and the things in it and then Emily says a magical evocation to wake up her much-loved cloth cat Bagpuss who lives in the shop and she leaves.

Bagpuss and his other toy animal friends would then wake up and come to life and the world would change from sepia to colour and they would discuss what the new object was; someone would then tell a story related to the object, often accompanied by a song which would generally draw from British traditional and folk music. After this the mice in the shop would mend the object while in squeaky voices they would sing to the tune of traditional song Sumer is Icumen In. There would be much banter and bickering between the characters (with pompous academic and wooden woodpecker Professor Yaffle notably often finding fault with the playful mice of shop), but by the end of each episode peace would be restored and the newly mended object would be placed in the shop window, hopefully to be seen and claimed by its owner. Bagpuss would then yawn and fall asleep, with both him and his friends becoming toys again and their world fading once more to sepia.

Writing and re-reading that now, it makes me realise just how odd and fantastical the world and premise of Bagpuss was. A shop that doesn’t sell anything? Whoever heard of such a thing? It almost seems like an accidental comment and rebuttal of the more rapacious aspects of commerce. Also curiously nobody outside of Emily ever seems to see or discover the shop when the toys have sprung to life and their world has become subtly and unreally full of vivid colour. And how did Emily know that they could be brought to life? Where did she discover the magical evocation that brings them to life? And was the “real” world actually sepia coloured, only turning into colour when Bagpuss woke up?

All I can say is that in the world that Bagpuss creates it all makes seamless sense and rational questions do not intrude.

Bagpuss is possibly the most fondly remembered and iconic example of Peter Firmin and Oliver Postgate’s Smallfilms work. As I wrote in A Year In The Country: Wandering Through Spectral Fields “it contains a sweetness, a uniqueness and gentle melancholia that arguably has never been repeated or equalled” and conjures up a sense of a warmly enchanting never-never land.

I first became aware of The Music of Bagpuss album via a review in Actual Size magazine (which was founded by one of the proprietors of Bopcap Books):

“Some 44 years ago, an audience of young children was introduced to and fell under the spell of the titular saggy old cloth cat in a charming, gentle, handmade stop-motion animation. If you need any kind of confirmation of the magic of this show, you only need to listen to the plucked strings of first track ‘Opening’ on this newly-remastered soundtrack album and you’ll be whisked back to that comfy, sepia-tinted world… That’s not to say only fans of the show can enjoy this album; the music here is a beautiful patchwork of British folk which stands up on its own as a really rewarding listen, much like The Wicker Man soundtrack before it… The 32 tracks which make up the main body of the album are – like all good folk music – a patchwork of traditional pieces, half-remembered tunes and pure improvisation.” (Quoted from Helen Skinner’s review of the album in Actual Size.)

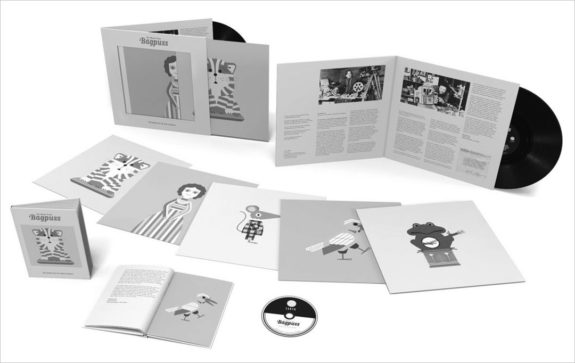

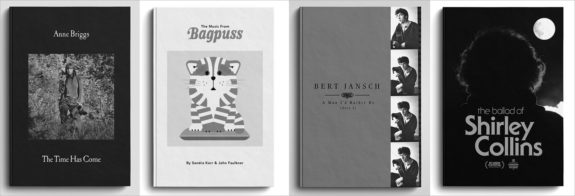

Earth Record’s release of The Music From Bagpuss is available in four different editions, including a CD in one of the hardback book style sleeves with inner pages which are being used more frequently of late, including Earth Records reissue of Anne Briggs’ 1971 album The Time Has Come, various of their Bert Jansch releases and their release of the DVD and soundtrack CD of The Ballad of Shirley Collins documentary. These “bookbacks” are a rather handsome way of presenting CDs and DVDs and I wish more people used them, as there’s something about them that makes releases feel more precious or thought about in some way, particularly in contrast to say a standard plastic DVD case without even a booklet, as is often the case with releases.

There are 49 tracks in total on The Music From Bagpuss, including a number of outtakes and alternate versions, and there are also accompanying sleeve notes/essays etc on Bagpuss from Oliver Postgate’s son and illustrator Daniel Postgate, writer and comedian Stewart Lee, singer and songwriter Frances McKee who performed with The Vaselines, Sarah Martin of Belle & Sebastian and Andy Votel of archival record label Finders Keepers Records.

It’s always something of a treat to be able to revisit the folk and traditional music orientated soundtrack for Bagpuss, which was recorded by Sandra Kerr and John Faulkner, and to have it so well presented, restored and comprehensively collected as in this release is icing on the cake. Just writing about it now makes me want to go and relisten to The Miller’s Song and maybe rewatch the accompanying sequence, of which I have previously written that it is a:

“a lilting, life affirming and yet also curiously quietly melancholic song about the cyclical nature of farming and rural life, the growing of crops and the passage of those crops to the mill and eventually via the baker to become loaves of bread… The sequence goes on to include what seems like a curiously out-of-place and anachronistic modern combine harvester alongside a combustion engine tractor and delivery truck, while also showing more traditional milling methods.” (Quoted from A Year In The Country: Wandering Through Spectral Fields.)

The style of the series suggested the early twentieth century Edwardian Era but although it had a notable vintage quality as mentioned previously it more seemed to exist in a sepia-toned time all of its own. The sense of a time unto itself is also present in the artwork for the Music From Bagpuss album, for which the characters from Bagpuss have been reinterpreted by Hannah Alice in a contemporary illustration / graphic design manner. These bring to mind a retro styled but contemporarily produced children’s book illustration, with the uncluttered minimal vintage tinged illustrations adding to the atemporal nature of the world of Bagpuss.

Watching Bagpuss back when felt like being offered a brief view or portal into another magical otherly world, and I’ve written elsewhere about how it may have been a very early childhood influence and discovery of more left-of-centre or even subtly experimental forms of pastoralism which would quietly sow the seeds for A Year In The Country.

Similar themes are discussed in Andy Votel’s sleeve notes for The Music From Bagpuss, where he writes that “those fifteen minutes that followed shortly after lunchtime your TV set became a secret shop window”. He also writes of how he has wondered if his childhood watching and being entranced by Bagpuss and Emily’s shop of lost curiosities may have been one of the things that fuelled his future fascination with visiting dusty second-hand shops and hoping to find and then release “lost” music and objects. He also goes on to talk of how the music in Bagpuss, and in particular the dulcimer twangs that accompany Bagpuss coming to life and the mice’s squeaky re-worded version of Sumer is Icumen In, may well have subliminally stoked his obsession with The Wicker Man.

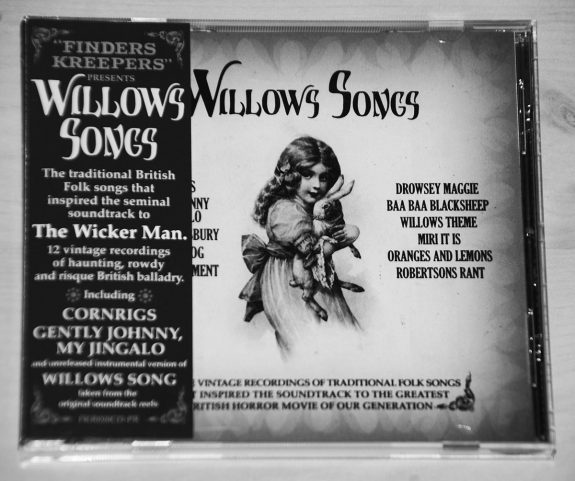

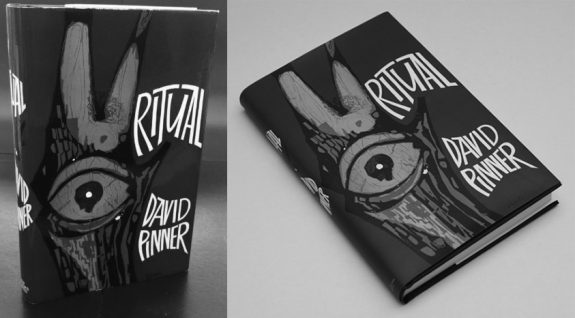

(Related to which Finders Keepers Records which he co-founded would go on to release the compilation album Willow’s Songs, which collected traditional British folk songs that inspired The Wicker Man soundtrack and also reissue David Pinner’s novel Ritual, which was one of the inspirations for The Wicker Man, both of which I have written about before at A Year In The Country.)

And talking of magical worlds… Both Sarah Martin and Frances McKee talk about how The Mouse Mill episode is their favourite, something which they seem to share with a number of people. If you don’t know it, in that episode the mice in Emily’s shop appear to be able to make an endless supply of chocolate biscuits using breadcrumbs and butter beans, which to young viewers with a sweet tooth and limited access to money may well seem like a magical nirvana like ability (!) Sadly, it’s all just a ruse and sleight of hand as the mice are merely rotating the same one biscuit over and over again… ah, if only (! again).

Perhaps the lack of money being necessary at the shop is part of the magic of Bagpuss that has made it so enduringly entrancing for younger viewers with only pocket-money to spend and/or who relied on grown ups generosity and money in order to buy toys, sweets and so on; as Andy Votel says in his sleeve notes for The Music of Bagpuss, the shop was a place where “the toys themselves were the shopkeepers and mum’s purse wasn’t needed.”

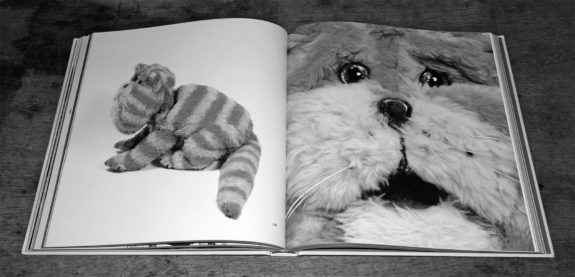

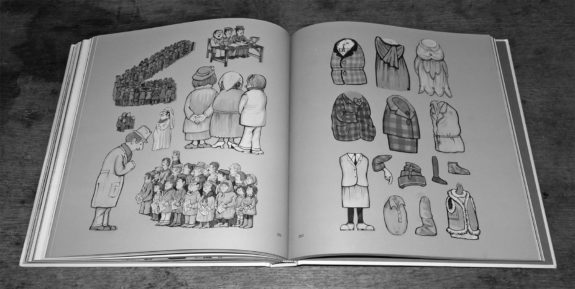

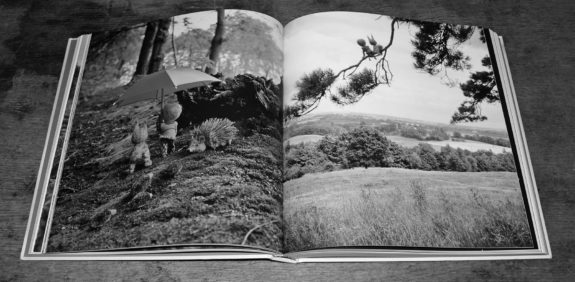

Jonny Trunk and Richard Embray’s The Art of Small Films book released by Four Corners Books collects objects, artwork, stills and so on from the Smallfilms archive. As is written on the cover “It’s a book full of pipe cleaners, cotton wool, wire and ping-pong balls” and it provides a behind the scenes or glimpse behind the curtain view of Bagpuss, The Clangers, Ivor the Engine, Noggin The Nog and so on.

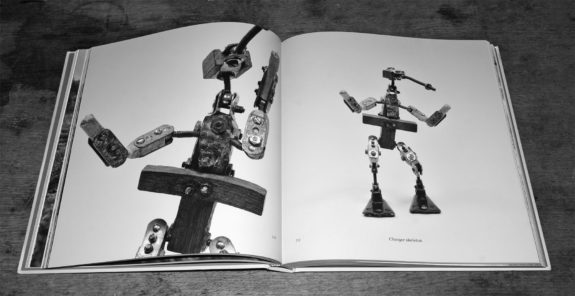

Interestingly it doesn’t break the spell of Smallfilms work and the worlds it created, which may in part be due to for example the adjustable skeletons of the figures in the series often having an intriguing folk art-esque quality and their own particular charm to them, which merely adds to the spell and worlds they create rather than puncturing them.

(Above: not a model for the long-lost Smallfilms’ folk art take on The Transformers but rather one of the skeletons for the Clangers.)

(Above: not a model for the long-lost Smallfilms’ folk art take on The Transformers but rather one of the skeletons for the Clangers.)

In the introduction to The Art of Small Films comic and writer Stewart Lee talks of how the book presents the archive of Smallfilms “as one would a collection of artefacts in an exhibition detailing some much-admired 20th century art movement, like Fluxus or Dada.”

It does indeed present objects from the archive in a museum-like and at times almost forensic manner but as well it brings to mind a rather poshly produced scrapbook.

That sense of scrapbooking, of the importance and sheer enjoyment in childhood that tracking down and collecting things could bring is something that may be considered to be present in a number of the archival books which Jonny Trunk’s has worked on (and also the archival releases of the earlier mentioned Finders Keepers Records). The books often focus on what was originally considered ephemeral or purely utilitarian, whether the archiving of one man’s collection of old sweet wrappers, tickets, badges etc in Wrappers Delight, library music cover art in The Music Library, flexi disc art in Wobbly Sounds or the 1960s and 1970s packaging design work of a supermarket’s design studio in Own Label.

The books can be seen as a form of elevating and focusing on such work in a way that, consciously or not, acknowledges that for much of the population the culture which people connected with and/or came into contact with on a regular basis, was more likely to arrive via television sets, record players or the aisles of Woolworths than art galleries and museums. They’re not in conflict with more fine art gallery and museum based archiving and exhibiting, but rather make the case for also valuing, archiving and studying creative work from other sometimes more overlooked, populist and/or utilitarian areas of previous decades’ culture.

Links:

- The Music from Bagpuss at Earth Records’ site

- Bagpuss at Bandcamp ! (Yep, I kid you not, he has his own Bandcamp page!)

- The Smallfilms Treasury

- The Art of Smallfilms book at Four Corners Books’ site

- Actual Size magazine (where I discovered about The Music From Bagpuss album)

- Bopcap Books (which is co-run by the founder of Actual Size magazine)

- The Ballad of Shirley Collins

- Jonny Trunk’s Wrapper’s Delight

- Wobbly Sounds – A Collection of British Flexi Discs

- Jonny Trunk’s Trunk Records

- Willow’s Songs at Finders Keepers Records’ site

- David Pinner’s Ritual at Finder Keepers Records’ site

Elsewhere at A Year In The Country:

- Detectorists, Bagpuss, The Wombles and The Good Life – Views from a Gentler Landscape

- Journeying Through The Seasons with David Cain (or maybe just July and October)

- Rounding the Circle with a Magical Saggy Old Cloth Cat

- The Ballad of Shirley Collins and Pastoral Noir – Tales and Intertwinings from Hidden Furrows

- The Ballad of Shirley Collins Trailer and Wandering Amongst Shadowed Furrows / The Hidden Reverse

- The Return of Old Souls; Fleeting Glances of Anne Briggs

- The Seasons, Jonny Trunk, the BBC Radiophonic Workshop and Howlround – A Yearning for Library Music, Experiments in Educational Music and Tape Loop Tributes

- The Telegraph Pole Appreciation Society and Accidental Art

- Further Appreciations of Accidental Art – Poles and Pylons

- Further Accidental Folk-Art

- “Here Be Monsters”: A Note on Ritual – introductions to and discoveries of Summer Isles predecessors via Ritual, Old Crow and the work of an archivist, literary sometimes pop-star

- Willow’s Songs