As I’ve written about before, there is an awful lot of photography online, in books etc that focuses on abandoned buildings, infrastructure etc. In part they often document the results of considerable amounts of endeavour that would have taken place to create the structures, which have now been left to crumble and be reclaimed by nature. The abandoned structures in such photographs are not all that dissimilar in this sense from if you come across an abandoned insect nest or hive, which are often incredibly intricate and complex, and which serve as faded snapshots of their previous inhabitants’ lives.

One subset of photographs of abandoned places and structures is that which focuses on abandoned villages. Within this subset there are a wide array of different styles of buildings, ways that they are collapsing and/or being reclaimed by nature, and reasons for the village’s abandonment. This post collects together just a few of them.

The above image is of an abandoned village on the island of Hirta, one of a group of the four most remote islands in the UK. The islands were inhabited for 2000 years but abandoned in 1930, after traditional ways of life were eroded, many young islanders emigrated, some were lost during WWI, and a young woman died from conditions which might not have been fatal if she had lived on the mainland and so able to more easily access greater medial help. In 1930 the last 36 villagers asked to be evacuated to the mainland, leaving behind a plate of oats and an open Bible in each cottage, which seems like a warm, welcoming, almost mystical and also terribly melancholic final gesture.

The village, nearer to a hamlet in size, appears to have been laid out more as a row than say a traditional clustering around a village green. Looking at the above photograph it appears some of the cottages have been restored, and there is also now another more recent building near to them – apparently in the summer almost as many people as the final 36 villagers stay on the island, and they include staff from island owners the National Trust for Scotland, volunteers, scientists and Ministry of Defence workers.

Apparently the defence workers are employed at a test rocket tracking station, a name which conjures up Quatermass-esque images of a lost age in the 1950s or 1960s when Britain had a space programme.

(The photographs of Hirta are from an article titled “Hirta Island Ghost Town” at the Atlas Obscura website.)

Wandering overseas, the above image is of a once thriving Chinese fishing village called Houtouwan, which has been abandoned and reclaimed by nature. It was once home to more than 2000 people but problems included those with education, food and delivery lead to its near total abandonment.

The photographs of the abandoned village are strangle beautiful, but also the way in which the buildings have been “greened” but retained their shapes is almost reminiscent of part of an extraterrestrial invasion in a science fiction film.

(The photographs of Houtowan are from an article at The Telegraph’s site.)

Next up is a more urban edgeland-looking image of The Boys Village in St Athan, Wales, which was a village-style holiday camp, which has had something of a varied history and number of uses. Along with part of the abandoned village subset of abandoned structures etc photography, because of its former usage it could also be considered an adjunct to photography of abandoned theme parks and fairgrounds, some of which I have written about before at A Year In The Country.

It was originally built as a holiday camp for the sons of miners, was requisitioned for military use during WWII, and then was refurbished and had a youth hostel and teaching facilities opened on site in 1962. Use of the village apparently declined due to the growth of cheap foreign holidays and the decline in coal mining in the Welsh valleys. In 1990 the Boys Club of Wales, which ran the camp, went into administration and the site closed and it was subsequently used for residential religious courses. It was sold in 2000 to a new owner and rented to a family who lived there and used it for farm storage, and it was then used from 2008 by Airsoft competitive shooting team sport enthusiasts. Over the years it has been subject to metal theft, vandalism and arson, although from what I’ve read in 2016 a planning application was made to build and renovate housing on the site, including 40% affordable housing. So maybe there’s life in the old “boy” still (insert groan here due to pun).

(The photograph is of The Boys Village is by Andrew Walch, and is featured in a WalesOnline article titled “Haunting, eerie and utterly mesmerising”.)

Above is an image of Tyneham, a village which was evacuated in 1943 during WWII in order that it could be used for military training. The evacuation was supposed to be temporary and only last during the war, but the villagers were not allowed back, and in 1948 the Army placed a compulsory purchase order on the land and it has remained in use for military training ever since.

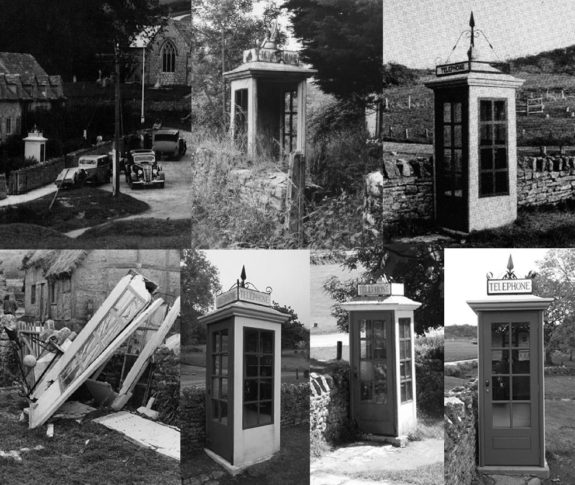

Curiously, in amongst the abandoned buildings at Tyneham there is what appears to be a restored period telephone box. However it is not one of the iconic and widely used metal “Red Telephone Box” style boxes but rather appears to be more ornate and in an earlier era’s style.

Looking it up, the box is made from wood and is one of the three different versions of the K1 telephone kiosk, which was Britain’s first standard kiosk that was introduced in 1921. The one in the photograph is not actually the original kiosk that was installed in 1929, but rather a replacement bought by the company which produced the 1986 film Comrades, during which an accident caused the kiosk to be completely destroyed. In 2012 it was restored with the help of an ex-GPO engineer, and given an interior that features authentic fittings and wartime notices, in order that it looked very similar to how it would have when the last villager left Tyneham on 19th December 1943. I don’t think it’s got a working phone mind…

(As an aside Comrades is an historical drama about the Tolpuddle Martyrs, a group of six agricultural labourers who were arrested and transported to Australia in 1834 for the apparently heinous offence of trying to improve their working conditions by forming an early trade union. It has been released in a restored edition by the BFI, and sounds as though it explores not dissimilar territory to 1975 rurally set film Winstanley, about social reformer and writer Gerrard Winstanley, which has also been restored and released by the BFI, and which I have written about at A Year In The Country. One for the, ever-expanding, list I think.)

Above is a visual timeline of the kiosk. Top left to right: when it was first installed in 1929, having been abandoned in 1981, and restored in 1983. Bottom left to right: after the kiosk was destroyed in 1985, the restored kiosk in 1983, it looking more worn in 2011, and after its restoration in 2012.

At their peak in 1992 there were 92,000 phone boxes in the UK but since the rise in popularity of mobile phones their numbers are somewhat depleted and it’s almost difficult to remember just how much they were once part of every day life.

A number of them have been converted to other uses, such as storing emergency defibrilators, so the boxes themselves are still there, if not the working phones. However I was quite surprised to read that 33,000 calls continued to be made on them per day in 2017, and in 2019 there were still around 31,000 operational boxes, with approximately 5,000 of these being the iconic red phone boxes.

(The photograph of Tyneham is from the taste* Café’s website. The photographs of the kiosk are from the Tyneham & Worbarrow website.)

Not to belittle other reasons and ways that villages have come to be abandoned, but there’s something particularly poignant about when villages have been flooded in order to create a reservoir. Even though their remains may occasionally reappear when water levels fall low, there is still a certain finality to their abandonment.

Above is a vintage image that shows the Derwent church spire after the village, along with Ashopton, was abandoned in the 1940s when Derwent valley was flooded in order to build the Ladybower Reservoir. Below are some more recent images which show when parts of the village reappeared in 2018 due to low water levels at the reservoir.

Some of the parts that resurfaced look curiously untouched by the years and erosion; the above railway line foundations could well be part of a new structure that’s just waiting to be finished.

While the remains of, I assume, a building’s walls in the above photography by Rob Eardley are nearer to something that may have been dug up as part of an archaeological dig, after it has crumbled away over hundreds or thousands of years.

(The 2018 photographs of Derwent village are from an article at the BBC’s website, and an article at the Derby Telegraph’s website.)

Elsewhere at A Year In The Country:

- Seph Lawless’ Abandoned Theme Park Images and the Duality of a Library of Loss

- The Quietened Village album

- The Quietened Village’s Library Of Loss; Volume #1/4a – (One corner of) A further library of loss

- The Quietened Village’s Library Of Loss; Volume #2/4a – Further Encasements And Bindings

- The Quietened Village’s Library Of Loss; Volume #3/4a – Light Catching Traces

- The Quietened Village’s Library Of Loss; Volume #4/4a – Ocular Encasment And New Arrivals

- Winstanley – Another Field In England

- Winstanley, A Field in England and The English Civil War Part II – Reflections on Turning Points and Moments When Anything Could Happen