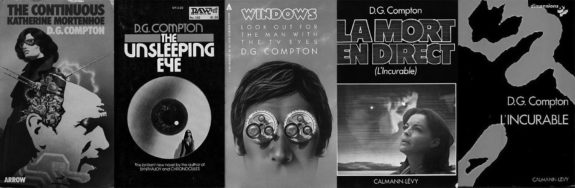

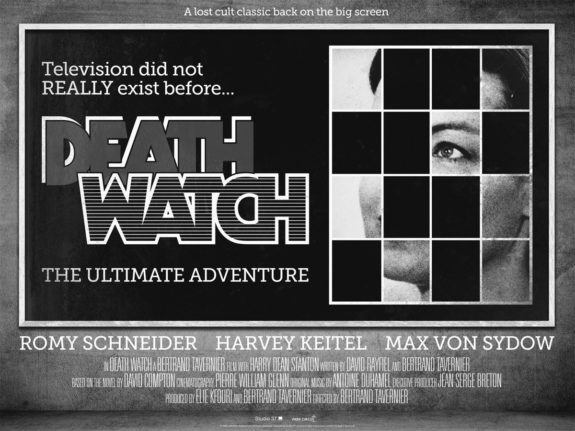

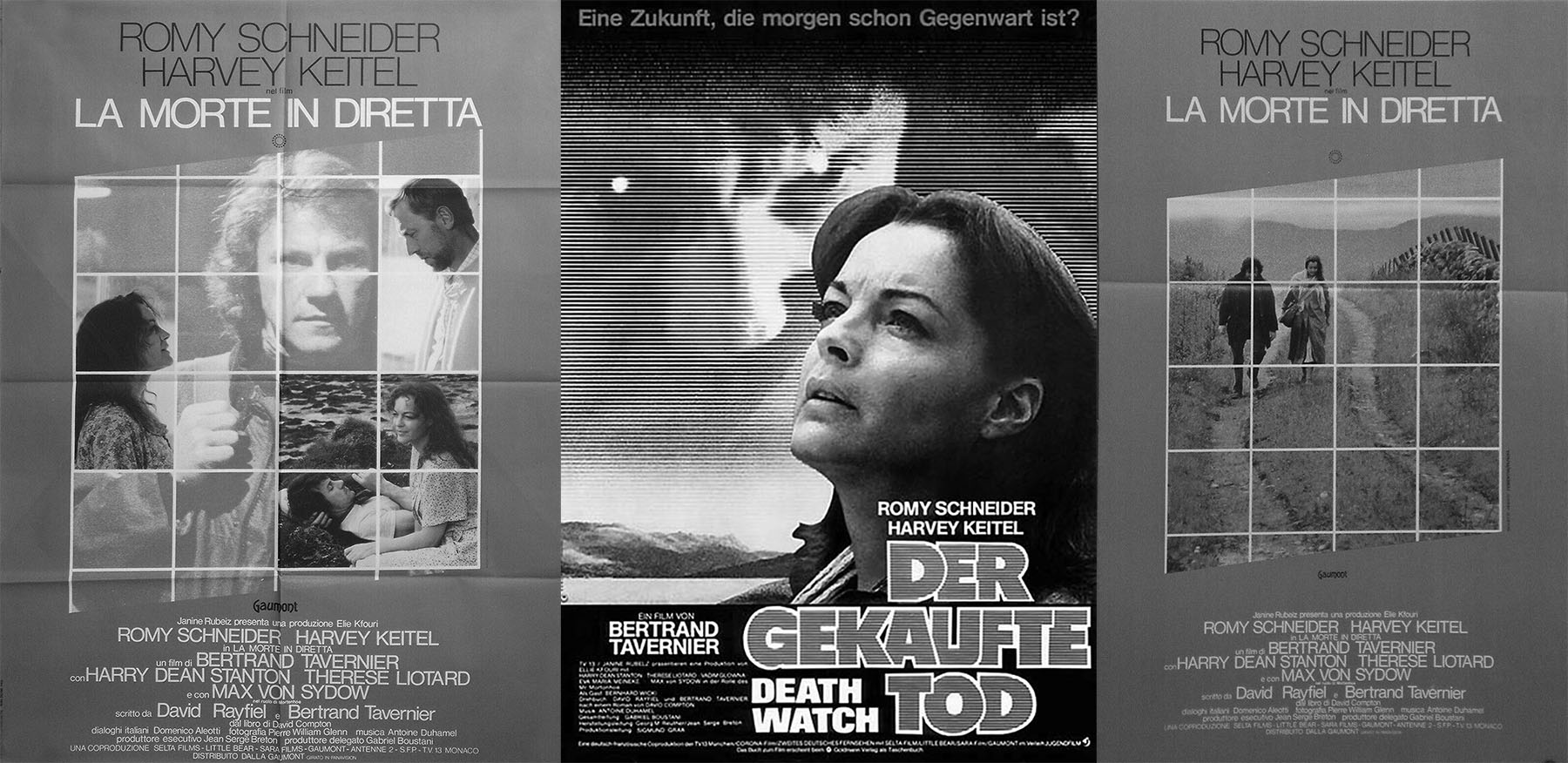

Death Watch is a science fiction film released in 1980, directed by French director, screenwriter, actor and producer Bertrand Tavernier. It is based on the 1973 novel The Continuous Katherine Mortenhoe (aka The Unsleeping Eye, Windows, La Mort En Directe and L’Incurable), written by David G. Compton. The film’s title is something of a misnomer, as it implies it might be a piece of sensationalist B-movie cinema, whereas it is actually an intelligent, non-exploitative and beautifully shot depiction of a woman’s journey through a subtly dystopic prescient near future.

First off, a synopsis of the plot (warning, spoiler alert!):

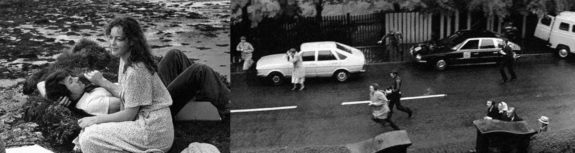

The film is set in a world where death from illness has become rare. Katherine Mortenhoe, the comfortably affluent resident of a large city, is diagnosed as having an incurable disease, and because of the rarity of this she becomes a celebrity and is besieged by journalists and autograph hunters. The television company NTV offer her a large sum of money if she will allow them to film her last days, which they will broadcast as a reality television show. Before even contacting her they begin to display adverts with her face on billboard posters, with the slogan “Television did not REALLY exist before…” She is heavily pressured by an NTV executive to sign a contract, with him saying that she can’t hide, that if she does they will just make a mystery and headlines out of it. Katherine eventually agrees to be filmed but actually goes on the run, thinking she has escape the terms of her contract.

While on the run she befriends a man called Roddy who, unbeknownst to her, is actually an employee of NTV, and who has had an experimental surgical procedure which implanted cameras and transmitters behind his eyes. Everything he sees is transmitted back to NTV, who use the footage as the basis for their reality TV show, without Katherine’s knowledge. However, the eye implants come with a high level of risk, as they will cease to work and he will become blind if they are left for longer than a short period without light. To prevent this Roddy variously uses drugs to stay awake, sleeps for brief periods with his eyes open, and carries a flashlight to shine on his eyes at night. He has had the surgery and taken on the work for personal financial reasons, as he wishes to give it to his estranged wife and son, possibly as part of a reconciliation attempt.

The resulting reality TV show is hugely popular, but Roddy keeps her away from places she might be recognised, or from seeing or knowing about the show. After passing through poverty-stricken and underclass areas of the city, they travel through rural areas and eventually arrive at a coastal area near to where Katherine’s ex-husband lives. When Roddy goes to the local town he sees Death Watch on the television in a pub and, being emotionally moved by it, begins to cry. He returns to the beach and has a form of breakdown, quite possibly because he has become emotionally connected to Katherine and realises that he has been acting in a mercenary and exploitative manner. Night falls, his eye implants subsequently fail, and he goes blind. When Katherine finds him, he admits who he is, and what he has been doing.

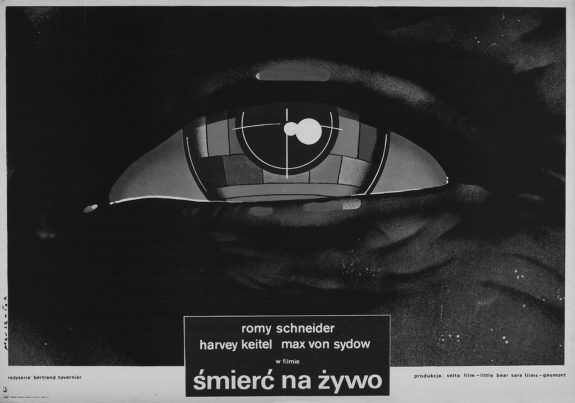

(The Czech version of the film’s poster.)

(The Czech version of the film’s poster.)

As they are no longer receiving the transmissions, NTV send a helicopter to track Katherine and Roddy down. They initially evade this and go to Katherine’s ex-husband Gerald’s house, which is in the countryside nearby. NTV track her down and phone Gerald’s home, and Gerald discovers that Katherine is not dying; in fact the symptoms she has been experiencing are due to the medicine she has been taking, which was given to her by a doctor, who was working in collusion with NTV. (However, Roddy did not know about this, thinking her illness was real, and some of his intentions seem honourable, as he talks of wanting to record the beauty of things). Katherine decides to take all of the remaining medicine at once, in order to die, saying that it is the only was she can win, and it is implied that she hopes the ensuing scandal will reveal NTV’s collusion in her fake illness, and end the career of the executive who convinced her to sign a contract with them.

When the NTV executive and crew arrive by helicopter, accompanied by Roddy’s wife, Gerald and Roddy threaten to kill them, with Roddy curiously seeming to have forgotten his own complicity in NTV’s actions, and they leave. Roddy’s wife stays behind and reconciles with him; he introduces her to Gerald, and somewhat curiously, the film ends without a sense that Gerald is overly mad at Roddy for his part in NTV’s plans, which are an inherent part of what lead to her decision to die. There is a final enigmatic voiceover by Roddy’s wife, where she says about Roddy:

“He told me he walked all that first day. Just walked. Doesn’t remember where. He didn’t come home. Well, why would he?”

The film’s arc is a depiction of Katherine’s journey; societally, physically and mentally. She journeys from her comfortable and fairly unremarkable life as a semi-creative worker, through the abrupt changes to her life that happens when she becomes a reality television star celebrity after her diagnosis. As her journey progresses, initially there is a sense that she has been freed from society’s norms, expectations and conventions, when she breaks her television contract, ditches her previous way of life and goes on the run. Eventually, she has nowhere left to run, and it seems as if society’s strictures catch up with her. This journey is also reflected in the changing settings of the film, as she travels from more affluent city areas, through to underclass and poorer urban locations, out into more restful and sparsely populated rural and coastal areas, which enable a moment of pause and reflection, and also an apparent lessening of societal control and ease of surveillance. Eventually she is literally at the end of her journey, and also the landscape, at Land’s End, near to where her ex-husband lives, which in the real world is the most westerly point of mainland England and the county of Cornwall, a place on the tip of the “boot” of England’s land mass.

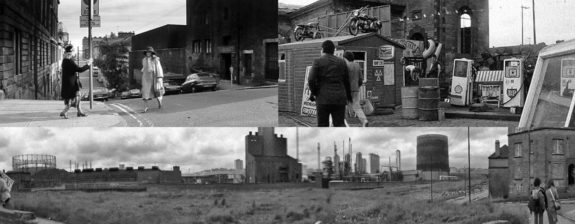

It was shot entirely on location in Scotland, with the people and authorities of its capital city Glasgow being thanked in the credits, and acts as a time capsule of the city at that time, and depicts a cityscape which is an evocative and contrasting mixture of distinctive and at times grand and ornate architecture, industry, edgelands and urban decay, with these elements at points being intertwined in the same shots and locations.

Death Watch does not seem all that widely known, and possibly its exploitation sounding title of Death Watch may have kept some more independent and art house film orientated viewers away from it. Also, at the time of writing, it is not all that easy to view in Britain, and it is not available to download or stream digitally. In 2012 it was re-issued to cinemas, and in the same year UK and US DVD and Blu-ray versions were released. However, the 2012 Blu-ray and DVDs released by Park Circus in the UK are out of print, and generally somewhat expensive second-hand, with the Blu-ray being near impossible to find, and scarce enough to almost imply it never actually existed. The 2012 dual Blu-ray and DVD edition released by Shout! Factory in the US is still in print, but requires a multi-region/American region code compatible player to watch them, which obviously considerably limits its potential audience in the UK. There are, however, some more accessibly priced in and out of print non-UK, European DVD releases of the film, under the foreign language titles La Mort en Direct and La Muerte en Directo, and Cinema Paradiso, the UK’s last remaining DVD and Blu-ray mail order company, has copies of it.

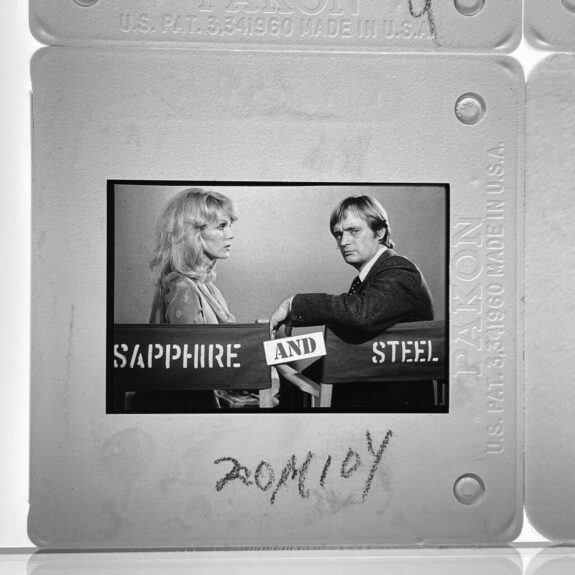

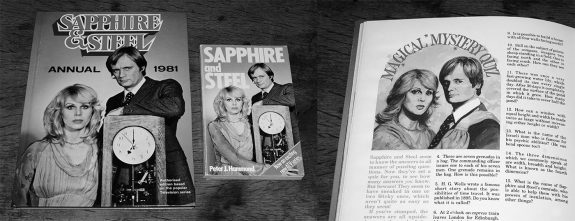

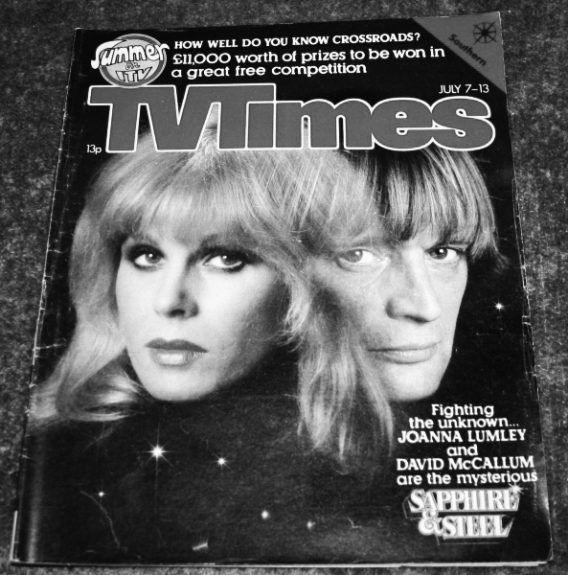

In a manner reminiscent of television series Sapphire and Steel and Jean-Luc Godard’s 1965 film Alphaville, there is a notable lack of visual representation of futuristic technology, gadgets and so on, with, for example, Roddy’s eye cameras merely looking like normal eyes. Also the interior and exterior locations, which appear to be filmed in the real world rather than on studio sets, have not been redressed to look futuristic. Other subtly portrayed indications of changes in society include a man canvassing in the street for a protest march in aid of living, i.e. non-computer, teachers (although there digital replacements are never seen), while some protest has been incorporated and neutered by society, as being a protestor is now a drop-out lifestyle and career choice, apparently paid for by the state, and in a curiously cyclical manner, protestors now even protest for better working conditions and pay. There is mention of border wars within Britain, and when Katherine and Roddy hitchhike in the back of a truck, eventually the driver stops and says “You must get off now, we’re not legal in this country”, implying there are separate and divided states within mainland Britain. Elsewhere there is an advert for jobs at a hydrogen waste reprocessing plant, suggesting that new forms of fuel are being used, but again, these are not actually seen in the film.

Also, as a further indicator that the film is not set in the then current world, Katherine works as a book writer, but her novels are written by a possibly artificially intelligent computer, which she has named Harriet. Rather than being a huge futuristic machine full of flashing lights, it is merely another device in her comfortable home study.

Katherine must do battle with the computer, in order to have her suggested plots accepted, with the computer seemingly only accepting those which can guarantee high sales, in a manner which reflects the film’s themes of a very commercially driven media, which is prepared to sacrifice all else in the pursuit of profit. As with much of the film, there is a prescient quality to this machine and the response to it, in particular the contemporary way that much of mankind’s and audiences’ interest, efforts and percentage of money spent often appears to be focused more on media related hardware, delivery service and platforms, rather than content and related creative expression:

“Does it make sense to have a machine named Harriet writing novels for us? Are we too exhausted from building you to make up our own stories?”

The casting is a surprising mixture of British and international stars: Katherine is played by renowned German-French actress Romy Schneider, who won the prestigious The César award (the French equivalent of an Oscar) twice, and was nominated for it three-time; future Hollywood star Harvey Keitel plays Roddy; Swedish actor Max Von Sydow, who was the pragmatically loyalty-free but rather humanely decent assassin in 1975 conspiracy thriller Three Days of the Condor, and memorably played the role of arch-villain Ming the Merciless in Mike Hodges’ high camp 1980 film version of Flash Gordon, plays Gerald; renowned American actor and musician Harry Dean Stanton, who across six decades appeared in numerous acclaimed films, including The Godfather Part II (1974), Alien (1979), Escape from New York (1981), Pretty in Pink (1986) and The Straight Story (1999), plays the NTV executive; a rather young Bill Nighy plays Katherine’s computerised novel creation assistant, well in advance of him becoming a characteristically slightly eccentric dashing elder leading man in numerous films; and Scottish actor Robbie Coltrane, who would go on to be the lead in the successful 1990s British crime series Cracker, and also appeared in the James Bond and Harry Potter films, has a cameo role as Katherine’s NTV assigned limousine driver, who she escapes from.

Perhaps because of the international cast, the way that if you visit Glasgow, one of the film’s main filming locations, it can, in part, feel closer in spirit to a European rather than British city, it being filmed in widescreen CinemaScope, and a French director bringing an overseas viewpoint, there is a subtle and hard to define, decidedly un-British, and at a remove from gritty social realism, aesthetic or cinematic visual sheen to the film. This aspect of it brings to mind the almost surreally vivid and beautiful Technicolor view of the British landscape in Powell and Pressberger’s film Gone to Earth (1950), or the depiction of a rundown estate on the edge of the countryside in Alistair Siddon’s In the Dark Half (2011), the second of which I wrote in A Year in the Country: Wandering Through Spectral Fields that:

“…the subdued, downtrodden landscape is given a subtle sheen which creates a sense that you are looking in on a magical otherly world… via its visual presentation there is a certain lush, soft beauty to the rundown estate and the nearby countryside: a refreshing view of such things in contrast with gritty, realist and sometimes-dour cinematic presentations of similar locales. This is partly due to the visuals of the film which are quietly sumptuous via the noteworthy lens work by Spanish cinematographer Neus Ollé, who director Alistair Siddons approached to work on In the Dark Half, as he said that he thought the viewpoint of somebody from outside of England would bring something unusual to the visual aspects of the film.”

The depiction of Glasgow in the film presents a very believable, day-to-day world, where Katherine is shown as living a comfortable, middle-class lifestyle amongst the more ornate and grander architecture of Glasgow, which is contrasted by the more down at heel market place / fair and the associated shanty town of tents, tenement blocks and church-run refuge which she passes through.

The billboard’s of Katherine’s face advertising the reality TV show, that are placed amongst the normality of Glasgow’s streets, have a jarring disjunctive effect that, rather than breaking the reality, and as with the central premise of NTV’s show in the film, seem worryingly prescient of subsequent real-world reality TV’s sometimes promotion and pursuit of the sensational and lowest common denominators, and accompanying potential audience voyeurism. Death Watch is also prescient in its depiction of the erosion of privacy, and the placing of public hunger for all-revealing gossip above all else, and a profit driven motive to feed that hunger. When Katherine says to the NTV executive that there are private things, he merely replies “Are there? Why?”

At times, almost inevitably, the film’s depiction of technology, or at least its implementation, have not proved all that prescient. One of the adverts shown during NTV’s reality TV show features an LCD solar watch, with the tagline “Some day, all watches will be made this way.” In 1980, when the film was released, the watch’s design quite possibly seemed futuristic, and was the kind of thing that high-flying executives would wear, but viewed today it is decidedly a period piece. Also, Roddy’s eye cameras involve a surgical operation, and in light of contemporary digital technology’s relentless upgrade cycles, let alone potential compatibility issues with other related hardware, such as the receiving equipment when that is upgraded, this seems a somewhat permanent and intractably inflexible way to gain access to stealth recording equipment. This misstep, in terms of predicting technological advances, reflects science fiction author William Gibson’s comments that if people do put actual pieces of digital hardware in their bodies, it will only be for a brief experimental period during its development and his discussing how effectively any cyborg-esque enhancements to our bodies are already happening, but it is in a physically external manner. These external enhancements include the likes of carrying devices such as phones, which effectively act as miniature computers that connect their user to systems of information, communication, media and so on.

(There is something of a link between William Gibson’s fiction and that of D.G. Compton who, as mentioned earlier, wrote the novel Death Watch was based on. Gibson is known for coining the phrase “cyberspace” to describe “widespread, interconnected digital technology” in his 1982 short story Burning Chrome, and in some of his fiction this is depicted as a three dimensional virtual reality which users enter and use to access and manipulate data, computer code, interact with other users etc. This literary and technological concept has a forebear in the work of Compton’s 1968 novel Synthajoy, which explores the social consequences of the development of a virtual reality technology which enables “unremarkable” people to enjoy the experiences of others who are more gifted or fortunate than themselves – themes which also interconnect with the technology based voyeurism of Death Watch and the original novel.)

The world depicted in Death Watch is a form of dystopia, but for many of its citizens, including Katherine, it seems like something of a materially comfortable one, where people often have a considerable amount of personal freedom in terms of how they live their lives. Katherine is placed under surveillance, but this is in order to provide broadcast entertainment content, rather than as part of a way of surveilling and controlling a population. Her surveillance is an apparently isolated case, and although she is placed under considerable personal pressure to agree to it, she is also financially well-rewarded.

This is in contrast to, for example, the world created in George Orwell’s iconic dystopian novel 1984, first published in 1949, in which the majority of the population live in poverty and are subject to severe rationing. They are also under the ever-watchful surveillance of two-way video screens, with all forms of media, literature etc being heavily censored, and at times even rewritten in order to create revisionist historical records. The population are required to pledge allegiance to the repressive political system and its iconic figurehead Big Brother, with transgressors being subject to incarceration, and brutally applied physical and mental forms of coercion and brainwashing.

In a connection with another iconic literary dystopia, Death Watch has a similarity with Aldous Huxley’s dystopian novel Brave New World (1932), in terms of the development and use of psychotropic drugs. In Huxley’s novel people take an officially sanctioned soothing, happiness inducing drug called soma; in Death Watch there is also open use of legitimate psychotropic drugs, but they appear more varied and specific. They include ones which “deepen the sense of beauty and awareness of awe”, alongside the self-descriptive “memory hype” and also the “unsleeping pills” which Roddy takes. And, as in Brave New World, in Death Watch there is a dictatorial expectation of happiness; when Katherine visits her father in old age residential home, the residents (or should that be inmates?) are kept in a happy state through the use of drugs, but this appears to be in an enforced manner, and without consideration of their free will.

Elsewhere, in Death Watch, social engineering techniques are shown as being present, but not overly aggressive or overt; in a warehouse-style supermarket a loop plays softly and continuously, saying “Don’t steal, you’ll feel so much better… pay for everything, you’ll feel good…” The audio is meant to play at a level which is not consciously audible, and to effect shoppers subliminally, but it is broken, and so can be heard. This isolated incident in the film suggests that such techniques may be present in a more widespread manner, but unknown to the population.

While Katherine’s lifestyle may appear reasonably comfortable and affluent, not all of society are shown as living like this. Class divisions are depicted in the film, with it being inferred that they have a constructed and politically engineered nature. After Katherine has received her payment from NTV, she and her husband go to a place in the city which is a cross between a fair and a market, where some of those lower in society’s strata trade. It is full of stalls selling bric-a-brac and junk, old mattresses, exotic masks and so on (which, as an aside, are often displayed in a quite artful manner that brings to mind outsider art created from found objects). Katherine’s husband asks a soup seller if the dole, i.e. the money provided by the state for those in poverty and/or out of work, is enough to live on. The soup seller replies “It keeps us downtown, that’s what it’s for, isn’t it?”, to which the husband can only reply “I suppose so.”

The enforced and controlled nature of class divisions, is also demonstrated when Katherine has given her NTV limousine driver the slip, and stays overnight in a church run refuge. There a priest says that those who wish to leave the city can, but they will not be able to re-enter, as their fingerprints are recorded, in order to stop them coming back.

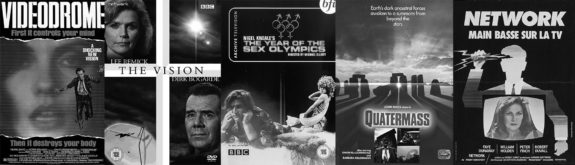

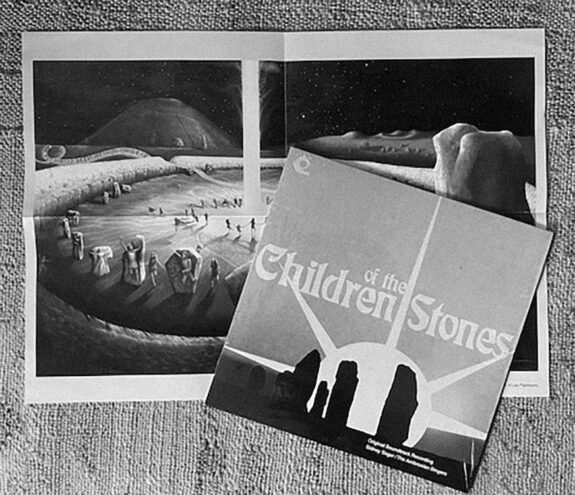

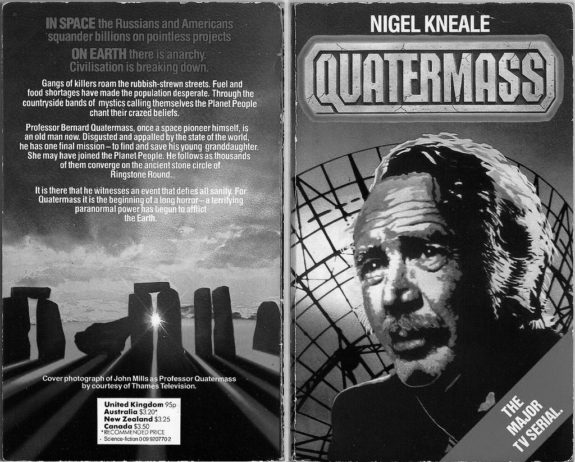

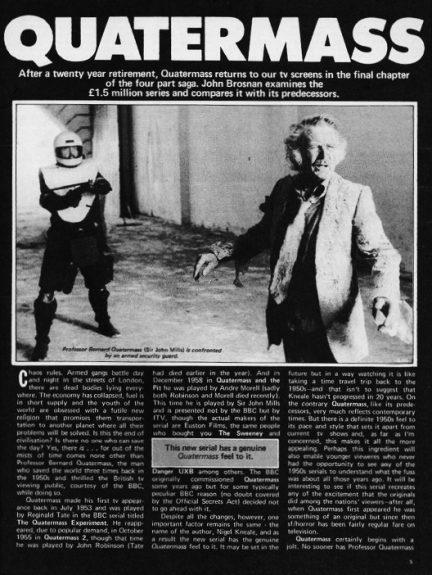

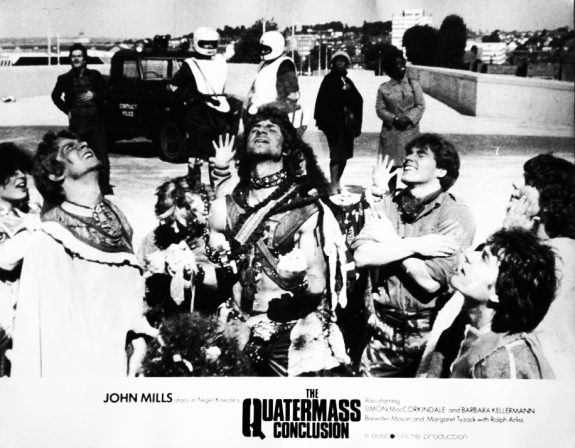

Death Watch could be considered part of a lineage, almost mini-genre, of cinema, and even television, which looks critically, askance and judgingly at television, warning of its potential as a corrupt and/or corrupting medium. Other films and televisions in that mini-genre might include David Cronenberg’s Videodrome (1983), BBC television drama The Vision (1987), Network (1976), Nigel Kneale’s Year of the Sex Olympics (1968) and the Titupy Bumpity section of his final series of Quatermass (1979). More on those another time…

Elsewhere:

- Death Watch – Cinema re-release trailer

- Death Watch – Park Circus DVD and Blu-ray

- Death Watch – Shout! Factory DVD and Blu-ray

Elsewhere at A Year In The Country: