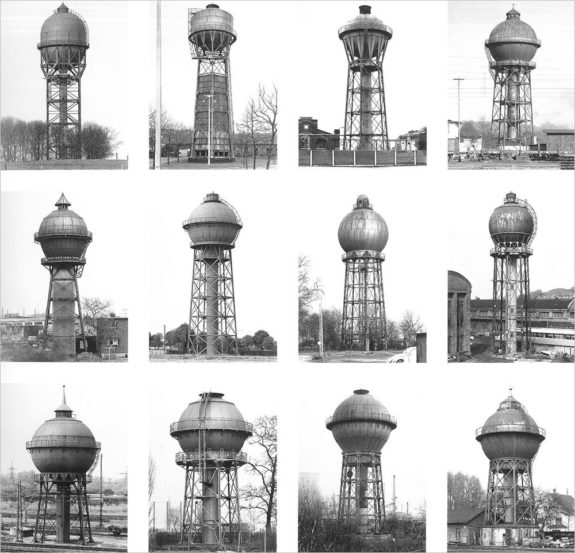

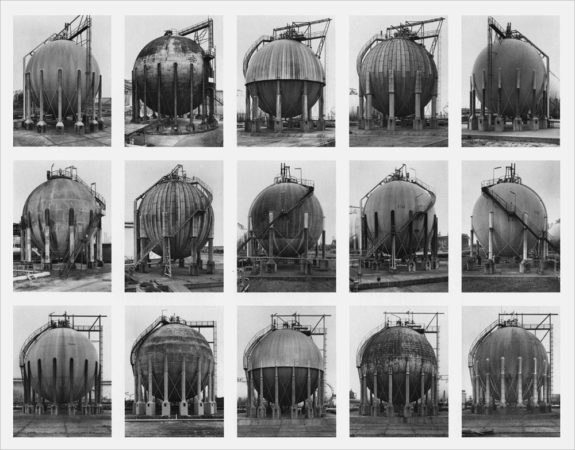

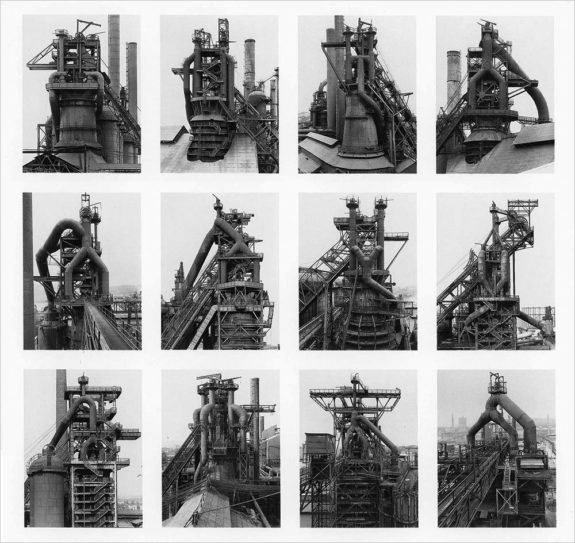

Hilla and Bernd Becher were a husband and wife photography duo who for forty years photographed and classified disappearing industrial architecture in Europe and America.

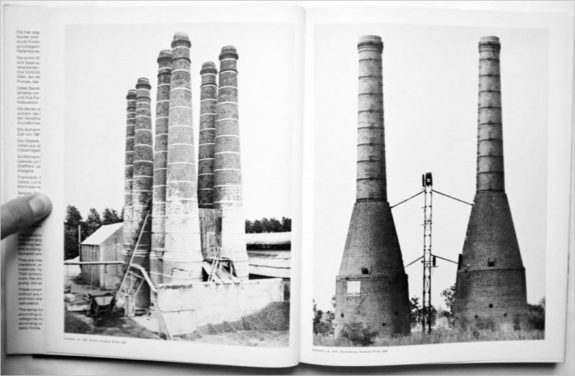

The resulting images work both as near forensic documenting of such architecture and also a form of art project, one which could be considered to utilise these structures as found objects.

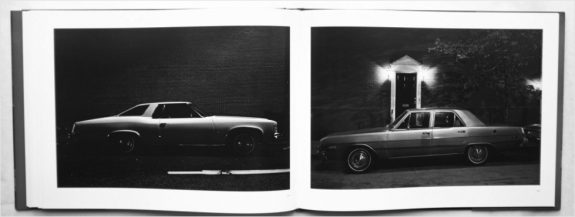

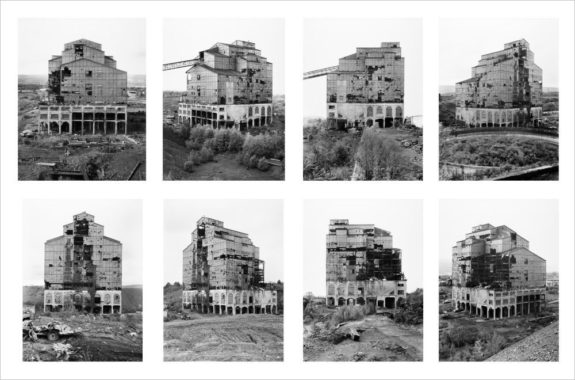

Often they grouped similar structures together, sometimes presenting a number of them in a grid. At such times the similar but different design of the structures brings to mind both British radio DJ John Peel’s comments about the band The Fall when he said “They are always the same; they are always different” and my comments in A Year In The Country: Straying From The Pathways about the photographs in Langdon Clay’s book Cars: New York City 1974-1976, which focused on cars parked in the city at night:

“Although the book consists of page-after-page of purely stationary cars at night, it does not impart a sense of mere repetition or monotony. Rather, the endlessly changing character of the cars, sometimes even seeming to morph from one to another, and the small details in the backgrounds of the photographs such as the changing businesses that stand behind where the cars are parked, the fallout shelter sign next to a meat company and its inspection certificate and so forth, keep the viewer entranced.”

People very rarely appear in Clay’s car photogaphs but in the Becher’s photographs they, or even any sign of them, is largely or totally absent. This at times, when accompanied by structures which are dilapidated and crumbling, can cause the viewer to consider the Becher’s images to be documents of a science fiction-esque post-apocalyptic scenario.

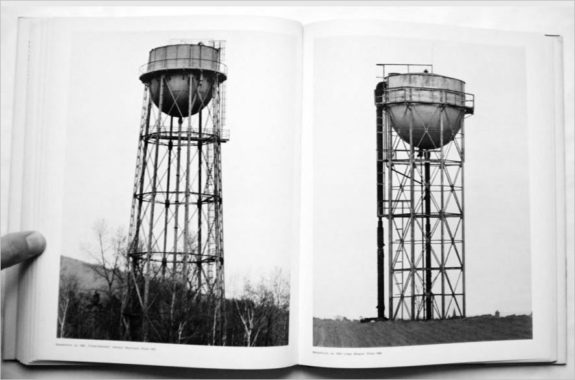

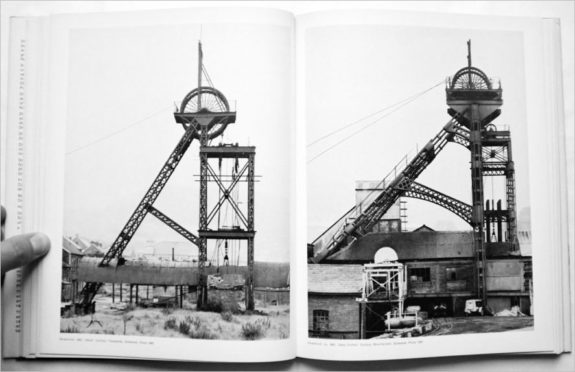

The subtle differences and similarities between the grouped structures in the Becher’s photographs is also emphasised by them choosing to adopt a rigorously uniform, although not restrictively formalist, technical approach to their photographs; all the images are in black and white, have the same portrait orientation and appear to be in the same aspect ratio, while structures in the same grouping all seem to have been photographed from a similar distance.

The Becher’s photographs may also be considered to be subtly imbued with a sense of loss. However just as knowledge of the dysfunction and troubled history which has at points accompanied high-rise Brutalist / modernist housing can serve as a check or balance to any tendency to over romanticise it, an awareness and acknowledgement of these structures’ working reality and possible history can also provide a sense of balance. It is not improbable that the more industrial of the structures in the photographs have a history which involved extremely hard, even at times dangerous, work that took place in challenging conditions, that they may have polluted or in other ways scarred the landscape and so on.

The structures in the Becher’s photographs are largely decidedly and almost purely utilitarian and little thought and effort appears to have been spent on enhancing their visual aesthetics or creating unnecessary ornamentation. However despite this there is a form of overlooked Brutalist-like beauty to some of the structures, which is captured in the Becher’s photographs. The structures in their phonographs could also be considered as another example of what I describe elsewhere as a form of accidental utilitarian art, in relation to the likes of telegraph poles and electricity pylons.

Related to which, the Becher’s photographs have come to be associated with art and sculpture rather than being seen as a form of documentary orientated industrial archaeology and they received an award from the Venice Biennale arts organisation not for photography but rather sculpture, due to what was considered their ability to illustrate the sculptural properties of architecture.

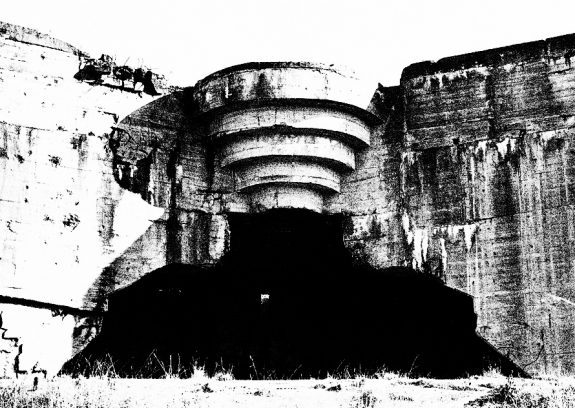

The sense of unexpected beauty that the images convey and the Becher’s focusing on fading and abandoned utilitarian concrete structures, alongside creating work which combines the characteristics of both documentary and expressive art photography also connects with the work in Paul Virilio’s book Bunker Archaeology (1975), in which he documented abandoned World War II bunkers:

“[Virilio’s bunker photographs] contain a curious and surprising, considering their nature, beauty or even poetry; they have a unifying flow or philosophy to them despite their once aggressive and defensive intentions” (Quoted from A Year In The Country: Wandering Through Spectral Fields.)

The Becher’s first photobook was published in 1970s and is called Anonymous Sculptures aka Anonyme Skulpturen (the title of which is a reference to Marcel Duchamp’s iconic, controversial and influential readymades work), copies of which can now cost hundred or even thousands of pounds, although a number of their other books are still in print and/or are more accessibly priced in used condition.

Reflecting the utilitarian nature of their subjects, a number of their books features minimal straightforward descriptive titles such as Cooling Towers, Gas Tanks, Coal Mines and Steel Mills, Watertowers, Grain Elevators, Mineheads, Stonework and Line Kilns etc.

Anonyme Skulpturen can be viewed at Josef Chladek’s site, in which he collects his photographs of photography and other books (the photographs of the Becher’s books in this post are from his site). The site is a rather fine resource and I expect something of a labour of love, in which by photographing the actual books he documents both the images they contain and also the physicality and design of the books.

Links:

Elsewhere at A Year In The Country:

- Paul Virilio’s Bunker Archaeology and Accidental Utilitarian Art

- Reflections on Brutalism – A Return to the Experimentations and Aesthetics of This Brutal World and Paul Virilio’s Bunker Archaeology

- Bunker Archaeology, The Quietened Bunker, Waiting for the End of the World, Subterranea Britannica, and The Delaware Road – Ghosts, Havens and Curious Repurposings Beneath our Feet

- Poles and Pylons and The Telegraph Pole Appreciation Society – A Continuum of Accidental Art

- Further Appreciations of Accidental art – Poles and Pylons

- Langdon Clay’s Cars – New York City, 1974-1976 – Part 1 – Post-Populuxe Ghosts That Brood While the City Sleeps

- Langdon Clay’s Cars – New York City, 1974-1976 – Part 2 – Totemic Spectres and Signifiers