Within culture which could be loosely labelled as Southern Gothic or Gothic Americana there is often a mythical take on the American South which has parallels with work in the UK that has come to be labelled as wyrd, otherly pastoral or weird Albion-esque. Both often have deep roots in the land and folklore, which is accompanied by a sense of the landcape being layered with hidden or unknown stories, which can be personal, spiritual, historic, geographic, fantastical, paranormal or a mixture of these and more in character.

Both wyrd and Southern Gothic etc work often features rural locations, which at times are shown as being unregulated, untamed and sometimes overlooked places, where the old ways persist. These places become psychic edgelands on the fringes of civilisation, in which the modern world has not quite yet taken hold, and where the norms, laws and regulations of conventional society do not fully apply, have been cast aside or are not abided by. Also they often portray rural areas, and sometimes their populations, as the “other”, as being separate from and unknowable to the urban and city based, and can also at times contain a sense of threat.

Some work which has been labelled as Southern Gothic can be viewed as both a critique of modernity, and also as providing space to explore social issues and reveal the cultural character of the American South. Although generally not strictly fantastical, there is often a magic realist element to this work and “a tension between realistic and supernatural elements” (Marshall Bridget, Defining Southern Gothic. Critical Insights: Southern Gothic Literature, 2013), alongside featuring characters who may be involved in the African-American folk spirituality of hoodoo (aka low country voodoo).

Within Southern Gothic / Gothic Americana work there is often a strong sense of spirituality, which connects with a wider sense of deeply embedded religion within the South. This takes in the aforementioned hoodoo and also Christian religious beliefs, which can be considered divergent from mainstream religion in a number of ways, including the strength of conviction of its believers and the manner in which they express their beliefs. It is frequently characterised by a devout belief in literal deliverance and damnation – of heaven, hell and the rapture – and also through the rituals of a number of its adherents, which can include snake handling, speaking in tongues and full immersion baptisms in rivers.

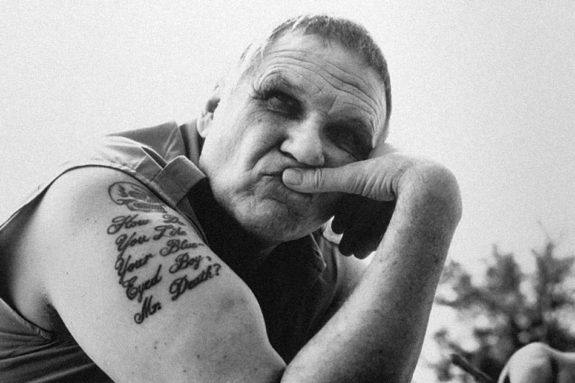

(Above: author and educator Harry Crews.)

(Above: author and educator Harry Crews.)

Part of the lineage of Southern Gothic work is the Southern Gothic subgenre of American literature, which has had 20th century work by Harry Crews, William Faulkner and Cormac McCarthy associated with it. This often has a distinctive aesthetic and atmosphere where flawed, disturbing and eccentric characters live in warped rural communities of the American South. Such literature frequently has decayed or derelict settings, grotesque situations and sinister events which relate to or stem from the poverty, alienation, crime and violence featured in them, which can result in despair and madness.

These are themes which can also be found in some of Daniel Woodrell’s novels, such as Tomato Red (1998), which depicts a small town edge-of-rural Southern hardscrabble way of life, where many of the characters have a fatalistic acceptance that things are just how they are or will only end badly.

Southern Gothic related themes have also been explored in other more recent work, such as Walter Moseley’s series of novels about the unofficial / private detective Easy Rawlins (1990-), in particular the Easy Rawlins origin novel Gone Fishin’ (2002). In contrast to the majority of Easy Rawlins novels, which are often set in urban Los Angeles, Gone Fishin’ takes places in the American rural South, and features a witch-like character named Mama Jo, who practices a form of voodoo, and administers an effective form of medical aid based around folkloric remedies rather than traditional Western medicine.

Alongside such literary work, the genre of Southern Gothic music, which is also known as Gothic Americana or Dark Country, explores similar themes and often has interconnected dark lyrical subject matter. Musically it draws from traditional country, folk, blues and gospel, alongside contemporary rock but in terms of its themes and atmospheres it appears to also take its influences from Southern Gothic literature. A prime example of this would be 16 Horsepower, who were active between 1992 and 2005, having been founded by David Eugene Edwards and Pascal Humbert, who were joined for the bulk of the band’s existence by Jean-Yves Tola.

16 Horsepower’s work has a notable haunting quality, with their releases invoking religious imagery and dealing with conflict, redemption, punishment and guilt. Although their work draws in part from gospel and religion, it is not so much a form of straightforward religious revivalism but rather contains a sense of being haunted by sins, of telling the stories of cast out and lost souls left to wander the land and forests as they seek or are unable to find redemption.

(The background of 16 Horsepower is deeply intertwined with Southern religion, as co-founder David Eugene Edwards spent much of his youth accompanying his grandparent as he travelled from town to town in order to preach.)

Working as Lillium, Humbert and Tola have also released three albums during and post 16 Horsepower, and their album Short Stories (2003) is well work seeking out. As with 16 Horsepower, it continues along a Gothic Americana path, and also conjures atmospheres of lost souls seeking redemption but, as with much of 16 Horsepower’s work, this is often depicted in an abstract sense, in contrast to some of Edward’s more directly religious orientated post 16 Horsepower solo work, and it creates an evocative, timeless sense of the landscapes and dusty plains of America.

The sense of an untamed, unknown and at times mystical South has been frequently used in film and television dramas and documentaries, often of a mainstream, critical and/or commercially successful nature. These include the steamy moral swampland of the vampire orientated True Blood (2008-2014); the folkloric/occult-like characteristics of crime in the first season of True Detective (2014); the unfettered sexuality, self hatred, guilt, back land swamp living and recidivist characters of Paperboy (2012); the urbanite tourists or military personnel incurring the wrath of Southern folk and being hunted down in the forests, swamps and rivers of Deliverance (1972) and Southern Comfort (1981); the independently produced and released but fairly high-profile theological action-horror Red State (2011), where in a small Southern Town an extremist religious community baits, entraps and disposes of what it considers decadent outsiders; the culture clash between urban sophisticates and Southern ways in Junebug (2015); and via a documentary road trip through the Southern landscape and its creative, personal and religious edgelands in Searching for the Wrong-Eyed Jesus (2003).

The rural American South is also the setting for the preternatural unexplained occurrences of Takashi Doscher’s independently produced film Still (2018), which is set in North Georgia’s Appalachian Mountains. As with some of the aforementioned culture, and other work which has been labelled Southern Gothic, Doscher’s film utilises and/or explores a sense of the American South as a potentially threatening, mystical or unknown “other”.

It tells of a young-ish married couple who live on an isolated rural farm, and initially it seems as though it will be a variation on Deliverance and Southern Comfort; two hitchhikers, who have a contemporary hipster-like youthful style that marks them as “not being from around these parts”, come across a young woman in the woods. When they ask for directions her behaviour seems a little off, hesitant and stilted but after a moment or two she appears to warm to them and offers them food. Played by Lydia Wilson, who also played the lead in the rural Britain set supernatural drama Requiem (2018), she has a visually very striking and distinctive appearance and this, accompanied by her manner, makes the viewer question if there is something of the preternatural siren about her.

As she walks with them towards her farmhouse, her partner tears across the field in his pickup truck, and seems extremely irritated and angered by their presence and also how they found the location of their farm. The hitchhikers are genuinely bewildered by his actions (“Is that a gun?” says one of them disbelievingly), in a manner which seems to be setting up film as a stereotypical depiction of city folk not understanding the ways of rural dwellers, and deadly conflict between the two groups. Despite his partner’s pleas not to, the young farmer drives the hitchhikers off at gunpoint, and presumedly their deaths.

However, the film is not a straightforward rerun of Deliverance / Southern Comfort tropes of deadly outsider rural Southern types, and this is intimated by the introductory sequence of old and modern half-toned newspaper covers, which show the couple looking the same age in the Prohibition era (i.e. 1920-1933, when the production and consumption of alcohol was prohibited in the USA). Although it has a preternatural premise, Still does not rely on genre shocks, action or special effects, but rather it is a meditative film which slowly draws the viewer into a beautifully portrayed, secluded and out of kilter rural world and couple’s life. Ultimately, as with Peter Strickland’s film The Duke of Burgundy (2014), in which as in Still a couple live a largely insular and out of kilter life, it doesn’t eschew but is also not purely or overly focused on the more genre or provocative aspects of its story, and becomes in large part an exploration of conflict, balance and acceptance in relationships.

The couple appear to be hiding some form of secret and, in particular the husband, do not want people on their land, nor for them to know how to get there. They live simply in an off the grid manner in a wooden farmhouse, which does not have electricity, running water, nor, apart from their pick up truck, any signs of modern conveniences, appliances, televisions, telephones, computers etc. How they dress also seems to hark back to earlier time, and as does the manner in which they live, it has a rustic simplicity to it, almost as though they are living in a self-contained time warp.

Another young hitchhiker, who was revealed in the newspaper covers of the introduction as having a rare form of terminal illness, is shown escaping from her hospital treatment, and then being lost in the woods. Due to her illness she collapses in the field next to the farm, and is subsequently shown waking in bed in the farmhouse. The husband again seems angered and wants her gone, but eventually he changes his mind, agreeing that she can stay – first until dawn, and then until the end of the week, with him expecting her to earn her keep by chopping wood. She does this until her hands are worn and bloodied, when he tells her she can stop, and during her other chores we are shown the seriousness of her condition as she weakens and coughs up blood, which she hides from the couple. However, the wounds on her hands are subsequently revealed to have healed miraculously quickly.

It becomes apparent that the husband and wife have gained some form of immortality, and have been living in this area without ageing since the Prohibition era. They have become immortal due to the unexplained properties of water they found in a local cave, which is depicted in a flashback sequence where they are shown in the Prohibition era to have hidden there after fleeing from the wife’s oppressive, controlling, and fundamental religious fanatic stepfather (who, in a manner that seems to conflict with his beliefs, is involved in the bootleg alcohol trade). Having evaded capture they settle on a nearby abandoned and secluded farm. However their life has become restricted in a number of ways; in order to remain immortal they must regularly drink the cave’s water, meaning that they cannot leave the farm, and also so as not to raise suspicion about their non-ageing, they must live a low profile and isolated life separate from wider society.

Prior to them discovering the immortality inferring and miraculous healing abilities of the local water, and after an initial period of being very fractious with one another, the couple are shown as having an affection and love for one another, and to be living harmoniously on their secluded farm. By contemporary times, and after having not aged for the best part of a century, this seems to have degenerated. The wife has essentially swapped one form of oppression and captivity under the thumb of her stepfather, for another; that of clinging on to immortality no matter what the cost, a need to hide their secret from the outside world and subsequently being tied to one another and this secluded farm, due to both this need for secrecy, and to be near the cave’s water, alongside her husband’s resulting controlling paranoia, and the dysfunction and conflict in their relationship this has all caused.

That this conflict plays out against a backdrop of stunning, and in some ways idyllic seeming, rural meadow, forest and mountain areas, serves to contrast and highlight the dysfunction present in the couple’s lives, while also adding a visually striking character to the film.

Although it is more conventionally scripted and visually presented, Still’s depiction of possibly preternatural unsettled events, atmospheres and dysfunction in a visually lush natural and forested setting, and the film’s lack of traditional genre visual shock or special effects, is not all that far removed from the setting and atmosphere of Josephine Decker’s film Butter on the Latch (2014). Decker’s film is set at a Balkan folk song and dance camp in the woods of California, and in A Year In The Country: Wandering Through Spectral Fields (2018) I wrote that it “is imbued deeply with a sense of dread and dysfunction [and could be called] a slasher in the woods without the slashing”.

I also wrote in Wandering Through Spectral Fields that Butter on the Latch could be considered “a form of folk horror where ‘folk’ could be taken as implying ‘being from the wild woods’; [in Butter on the Latch] these are woods that seem both tamed and untamed, connected to civilisation and yet those within it have also crumbled away from it” – comments which equally could be made of Still, and the couple’s divergence and transgression from the wider conventional world, life and norms.

The presence of the hitchhiker in their home upsets the fragile dysfunctional balance of their lives, and during the film the husband and wife are shown to be increasingly at odds, and during one heated argument the wife forcefully states that how they are living is not natural, and she wants out.

(The “unnatural” nature of their lives is poignantly shown when the wife shows the hitchhiker a set of unmarked graves, which she says are her stillborn children. Although it is not explicitly stated, there is a strong implication that this has happened due to some side effect of the cave’s water and their immortality.)

The husband resists strongly and violently against any suggestion that they leave and become mortal again, and seems to be possessed by an all-consuming paranoid insecurity about losing his immortality, or of any outsiders knowing of their secret and potentially taking away their eternal life, and will carry out any acts he considers necessary in order to protect it.

After she has stayed with them for a while the wife “cures” the hitchhiker of her fatal illness by giving her some of the water from the cave, and she reveals the secret of it and their lives to her. However, in order for the cure to be ongoing, the hitchhiker will need to stay in the area and keep drinking the water.

Eventually a form of cycle of life occurs in the film; after intensely resisting it, when his wife nearly dies after she temporarily leaves the farmhouse and access to the cave’s water, the husband finally realises that their way of life is no longer tenable, and that they cannot continue to attempt to live forever. He cedes to his wife’s wish for their immortality to end, and leaves the farm with just one bottle of the cave’s water, and his wife soon follows. The hitchhiker becomes the new immortal resident, and she is also immediately shown as being prepared to carry out fatal acts of violence in order to protect her immortality, when she guns down two outsiders who damage the farm’s unlicensed alcohol still. This still is a vitally important component of an immortal life on the farm, as it is a way that anybody living there can earn money in an under the radar manner, and thus live there without needing to overly connect or be noticeable to the outside world.

In a final emotionally resonant scene the husband is pictured sitting on the edge of a mountain, with his last bottle of the immortality giving water depleted. When his wife finds and joins him she holds his hand; they appear to have found their affection, love and understanding of one another again, and to have decided to let themselves age and die, and subsequently all the ageing that they would naturally have been subject to quickly descends on them.

The final shot is from behind them, as they sit together affectionately overlooking the natural beauty of the landscape, with the only indication of their soon coming mortality and ageing being the rapid silvering of their hair.

This scene is reminiscent of the final section of John Boorman’s film Zardoz (1974), where a couple, who have helped destroy and escaped from the stasis and imprisonment of a world based around a privileged classes’ immortality, are shown sitting side-by-side in a cave. Via time lapse photography they rapidly age, their children appear, grow to mortality and leave, after which the couple solemnly hold hands and collapse into old age and then death.

In Zardoz immortality has created a dramatically unequal society where those not in the elite (the “Brutals”) live in a wasteland, and are violently controlled by a warrior class in order to provide for the immortal elite (the “Eternals”), who live in “The Vortex”, which is protected by an invisible barrier. There the Eternals live in privileged liberal but conformist luxury, and due to their immortality they have become sterile, experience extremes of aimlessness, ennui and, in some cases, are inflicted with a catatonic form of living death.

Although more subtly expressed in Still, both it and Zardoz can be viewed in part as a consideration of the mentally corrosive effects of immortality, with both the Eternals in Zardoz, and the couple in Still, being shown to be living in a gilded, and ultimately dysfunctional and doomed, cage of immortality.

The double-edged sword nature, and practical problems, of humans attaining immortality is a theme which has been explored numerous times and in notably varied ways in cinema, comics and literature.

One of the recurring themes in much of such work is that when people do not age, as all around them do, this inevitably leads to them arousing suspicion. This is the case in 2015 romantic fantasy film Age of Adaline, in which a permanently 29-year-old woman, who has accidentally gained immortality through an unexplained magic realist-like event, has to spend her entire life on the run to avoid suspicion and the attention of the authorities, scientists and so on. This has resulted in every few years or so her needing to change her identity, style and leave her current home area, and knowing that she can never fall in love, as she cannot live a normal life with a partner.

The practical difficulties which immortality brings about in modern society are explored in Ross Welford’s 2018 young adult novel The 1,000 Year Old Boy, in which an immortal and unageing young boy finds modern-day life increasingly difficult. For many centuries he and his also immortal mother evaded attention and suspicion of their non-ageing, by living quietly and separately from others, and as in Still often living in a secluded rural way more in keeping with previous times, or by adopting a portable transient lifestyle. Today they can’t even rent somewhere to live easily, as people “want to know everything about you”, i.e. they require references, bank details and so on, which due to their off the grid and/or under the radar lifestyle, that they have adopted to avoid suspicion, they do not have. Also the increasing use of digital records, and a related ability to cross reference information, has meant that it has become increasingly more difficult to hide their secret immortality, as those who do become suspicious are able to investigate and discover details of their living and being the same age in previous years and centuries.

In 1972 horror film The Asphyx, and 1992 black comedy Death Becomes Her, immortality is shown to have physical problems or side effects. In both, those who have attained immortality are shown to carry on living no matter what physical injuries they suffer. This leads to a central character in The Asphyx eventually living life as a disfigured wanderer through city streets, while in Death Becomes Her a narcissistic holding onto eternal youth and physical beauty leads to two of the immortal characters becoming physical parodies of their former selves, whose rotting but eternally alive bodies are patched up with putty and paint in a manner nearer to house restoration or temporary car repair.

Science fiction film In Time (2011) also takes a technological, but near magic realist in its unexplained nature, approach to immortality; it depicts a dystopian near future where people stop ageing at 25, when a 1-year lifespan countdown on their forearm begins. Lifespan has become a form of commodity, and has replaced money as society’s currency, with the wealthy owning more lifespan and effectively being immortal, while the mass of the population literally live day-to-day, or even minute-to-minute, as they attempt to earn more lifespan at low paid menial jobs. The film becomes a critique of class divisions and inequality, dressed up in high concept science fiction trappings, and is left open-ended as a Robin Hood-esque character and his partner, who has rebelled against her status as one of society’s lifespan rich elite, attempt to crash the system by stealing ever larger sums of lifespan, which they intend to redistribute throughout society.

Vampire genre films have been somewhat fertile ground in which to explore the potential dangers of immortality. In German vampire film We Are the Night / Wir Sind Die Nacht (2010), a group of immortal and unageing female vampires live an affluent and decadent nightlife orientated lifestyle. However, for one of them the unending nature, aimless repetition and hedonism of their immortality has resulted in severe apathy and dissatisfaction, something which is heightened by her estrangement from her mortally ageing daughter. While the group of vampires in We Are the Night have managed to provide themselves with a luxurious lifestyle, in 1987 neo-western vampire film Near Dark a family like group of vampires, made up of males and females with differing arrested physical ages, live on the margins of society, in a way that is nearer to a previous century’s American frontier and outlaw ways of life, and the film’s depiction of their fringe existence has some similarities with the earlier mentioned characteristics of poverty, alienation, crime, violence and madness which feature in some Southern Gothic literature.

In contrast to both We Are the Night and Near Dark, in playful comedy horror vampire film Vamps (2012), two immortal female vampires, who have remained eternally young women, live fairly normal lives, and are constructive members of society with regular jobs. However, as in all the above, their immortality ultimately proves problematic, and they decide that, while they have had a lot of fun being immortal vampires, “being young is getting kind old”. One of them has fallen in love and become pregnant, but the baby will not survive unless she becomes human again. They choose to become mortal by killing the psychotic “stem” vampire who turned them into vampires, which will end their immortality and vampirism. However, as in Still, once their immortality ends their physical bodies are subject to all the ageing that would have happened without their immortality, and it is revealed that one of the women has acted selflessly, as she has been alive for many years, and she ages and disintegrates into ash – and as in the ageing sequence in Still, there is a pronounced sense of both melancholy, and also of finding peace in the relinquent acceptance of a return to the natural order.

Links:

- Takashi Doscher’s Still

- Still’s trailer

- 16 Horsepower

- Lillium

- Butter on the Latch’s trailer

- Josephine Decker’s website

- Lazarus Churchyard

- Warren Ellis’ site

- The Twilight Time release of Zardoz

- The trailer for the Arrow Video release of Zardoz

- Ross Welford’s The 1,000 Year Old Boy

Elsewhere at A Year In The Country:

- Zardoz, Phase IV and Beyond the Black Rainbow – Seeking the Future in Secret Rooms from the Past and Psychedelic Cinematic Corners

- Wandering from the arborea of Albion and fever dreams of the land…

- General Orders No. 9 and By Our Selves – Cinematic Pastoral Experimentalism

- Requiem – Further Glimpses of Albion in the Overgrowth and Related Considerations

- The A Year In The Country: Wandering Through Spectral Fields book

- Bare Bones and Fellow Travellers in Rif Mountain’s Phase III

- Katalin Varga, Berberian Sound Studio and The Duke of Burgundy – Arthouse Evolution and Crossing the Thresholds of the Hinterland Worlds of Peter Strickland

- Andrew Niccol’s Gattaca, In Time and Anon – Striving for the Stars in a Brutalist Retro Future and Other Near Future Tales

- Kill List, Puffball, In the Dark Half and Butter on the Latch – Folk Horror Descendants by Way of the Kitchen Sink