At the A Year In The Country site there have been a fair number of posts that explored the cultural offshoots from The Wicker Man such as documentaries, different home releases of the film, related books and soundtrack releases etc but I thought it would be good to revisit the actual film.

It is easy to forget just how odd The Wicker Man (1973) is. Even after numerous viewings it retains an ability to shock, intrigue, unsettle and even possibly even beguile and confuse the viewer.

This may in part be due to its mixing of genres and themes; at times it veers towards being a musical, running through the whole film is a crime mystery, at points becomes more an erotic thriller, while it ends on a note of, if not actual horror, then at least terror during its ending. Accompanying all of which it explores complex and morally ambiguous debates around different belief systems and practices, both directly via the characters’ dialogue and indirectly via the results of their actions.

In terms of genres it could be connected with, one of the things that struck me when I recently rewatched it was just how much it includes considerable elements of the con artist movie. More on that later in the post.

I suspect that if you’re reading this you may well already know of the film’s plot etc but just in case, below is a brief synopsis.

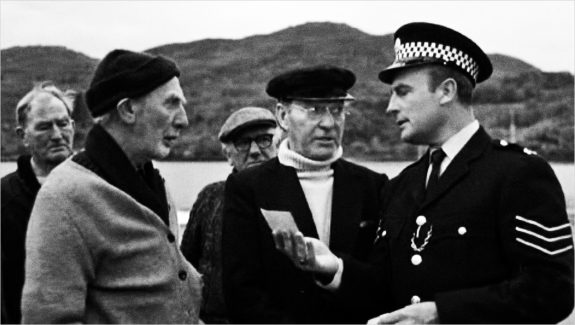

Directed by Robin Hardy from a screenplay by Anthony Shaffer and set in contemporary times, the plot focuses around Sergeant Howie, a pious and puritanically Christian police officer who receives a report of a missing child and travels alone via seaplane to the remote Scottish island Summerisle where she lived. The island has an economy largely based around agriculture and the growing of new strains of crops which are able to flourish in the island’s unusually temperate climate.

Sergeant Howie’s investigations are met with recalcitrance and deception by the villagers, and he is repeatedly shocked by them not following the Christian religion, instead having turned to the “old gods” and a form of pagan nature worship, which incorporates an uninhibited attitude towards sex and fertility, and incorporates folkloric rituals and song. Ultimately it is revealed that he has been lead a merry dance by the islanders and their patriarchal leader Lord Summerisle and that the sergeant is intended to be a sacrifice that it is hoped will restore their failed crops, which it is implied has happened due to them being grown in an area where they would not naturally be.

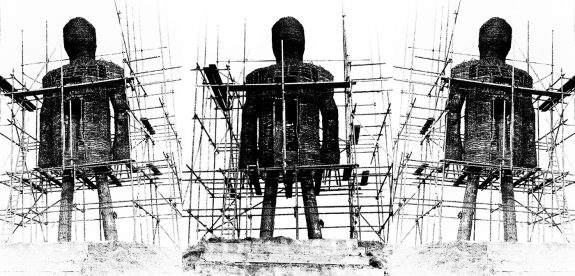

In the final sequence Howie is forcedly placed in a huge wicker man pyre structure, which is set fire to as the islanders serenade his sacrifice with a traditional sun worship song. As the wicker man structure burns, its head falls to one side and reveals the sun setting over the ocean.

(As an aside, looking back the film’s exploration of alternative lifestyles, pagan beliefs and “the old ways” could be considered to interconnect with the “psychic boom” in the 1960s and 1970s, when there was a considerable upsurge of interest in the paranormal, the occult etc which was accompanied by a growth in subcultural and mainstream media coverage of such subjects, alongside an increase in the release of related publications.)

Although the ending and Howie’s sacrifice are not easy viewing, their depiction, the reasons for what has happened and demeanour of those responsible are presented in a way that causes the film to stand apart from the gratuitous or almost nonchalantly callous inclusion of sadism that has become an increasing part of the horror, and other, genres:

“For [Christopher Lee who played Lord Summerisle], this is what sets the film apart from conventional horror movies: ‘The islanders are so sincere. Summerisle says [to Howie], ‘A martyr’s death – the greatest gift we can bestow.’ And everybody’s smiling. You know: what a lucky man you are! Joy, joy, joy. There’s no sadistic delight.'” (Quoted from “A Pagan Place”, Damien Love, Uncut, May 2002.)

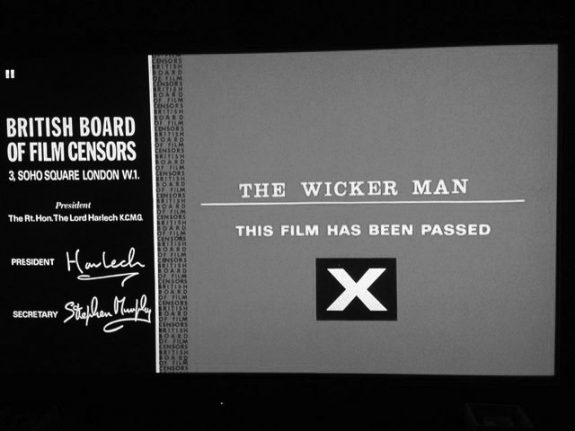

The film plays with a sense of reality and fantasy and it opens with text that says:

“The Producer would like to thank The Lord Summerisle and the people of his island off the west coast of Scotland for this privileged insight into their religious practices and for their generous co-operation in the making of this film.”

Having been released at a time before the ease of access to information brought about by the internet, the film’s audience is unlikely to have known that no such community or island existed, nor have been able to quickly look it up.

(There is a similarly named island called Summer Isles off the coast of Scotland but none of The Wicker Man was filmed there.)

The blurring of the lines between fantasy and reality in the film is also increased through it using a considerable number of songs that either draw from traditional folk songs and/or are similar in style and content. Alongside this it features a number of folk traditions, rituals and characters that also draw from real world traditions, and which lend a familiarity and layered grounding in semi-known and half-remembered reality to it, of which the film’s director Robin Hardy has said:

“What we hoped would fascinate people is not that they would think these things are still going on in Europe, but that they would recognize an awful lot of these things as sort of little echoes from either out of childhood stories and nursery rhymes or things they do at various times of the year… But they’re not dead. The thing about these beliefs is that people do these things today and not know why they do them. We call them ‘superstitions’. There are millions of people who know nothing about [ancient trees gods and mythology] who will… ‘touch wood’… [Such things] all have profoundly important and real origins in pagan belief.” (Quoted from “The Wicker Man”, David Bartholomew, Cinefantastique – Volume 6, Number 3, David Bartholomew, 1977.)

The changing use and depiction of music in the film further blurs the sense of reality and unreality. At times it is apparently played and sung by those onscreen in a fairly realist manner and appears to be a diegetic or natural part of the film’s world, such as during a sequence when a bawdy song is sung by the patrons of a pub, the music for which was recorded on location and played by those who appear onscreen. Elsewhere the film becomes more similar to a conventional musical as obviously studio recorded singing and instrumentation play, with at times only the vocals being mimed by the onscreen characters, while at other points both the vocals and the instrumentation are mimed, which blurs the lines between the “real” world of the film and its characters and its more obviously artificially constructed aspects. Also at one point the performance of music in the film possibly briefly breaks the fourth wall, which happens when an islander sings and performs an erotic song and naked wall thumping dance in order to tempt and seduce the puritanical Howie through his bedroom wall. During this she is accompanied by studio recorded non-diegetic instruments on the soundtrack which have no “real” world source in the film and she appears to look directly at and acknowledge the camera. The resultant continuous switching of modes adds a shifting sense of reality to the film’s world and the viewer’s perception of it.

There is also a further blurring of reality in the film due to it being shot in real world locations, meaning that there is an authenticity to them which connects with the film’s deliberately misleading introductory text thanking Lord Summerisle, and also

their appearance is not leant a potentially dated studio bound appearance. This sense of authenticity is added to by many of the islanders being drawn from members of the local public rather than being professional actors, and so subconsciously they seem “right” for their location. However, in contrast with the resulting sense of the film being located and grounded in the real world, although the film was set in contemporary times, many exterior signs of modern life such as street lights and television aerials seem to be largely absent, which adds an atemporal “out of time” aspect to the island.

The film also uses a recurring trope in cinema, that of islands and rural areas as places where it is possible for conventions and norms to be stepped away from, and their populations to be an unknowable or threatening “other” who have their own ways and beliefs that are at odds with wider society. As part of the exploration of this the investigating outsider Howie represents two forms of mainstream or conventional authority, being both a devout Christian and a police officer.

The clash between Howie’s beliefs and authority, and therefore those of the conventional and dominant society, and the islanders’ beliefs and Lord Summerisle’s authority throws up questions about assumptions of moral right and superiority around different forms of religion and authority. Accompanying this the film explores what happens when assumed positions of power and superiority are challenged in various ways, which in this instance involves a society wide lack of compliance and the individual who represents those positions being removed from their supporting infrastructure. When Howie, his investigation and authority are not met with cooperation by the islanders he, at least for much of the film, keeps straightforwardly ploughing on, assuming that somehow he will get to the truth of the matter. This may appear somewhat obtuse, or imply that he is not all that skilled as a detective, but may in fact be due to him being used to operating in a setting and society which respects his authority and the hierarchy and system he represents, and so he is essentially unable to correctly function, or understand how to, when that is no longer the case.

Howie is only on the island for two nights but the islanders’ lack of cooperation quickly has him and his rigorous adherence to the law coming apart at the seams. After exhuming the missing child’s supposed grave he finds only a hare in her coffin, which he had previously been told by the islanders she had transmuted into upon her death. The islander who has helped him in the exhumation just laughs mockingly at him discovering this, and when Howie confronts Lord Summerisle with his finding the response he receives is a knowing and dismissive humouring of him. Thus far in the film whenever in public Howie has been wearing an immaculately kept uniform, in a way that both represents and heightens his own personal sense of authority and also his controlled, buttoned up and even priggish and prissy personality.

(Edward Woodward who played Howie is said to have worn a police uniform two sizes too small in order to enhance the sense and appearance of the character as controlled and overly buttoned up.)

In the above confrontation with Lord Summerisle his tie is loosened and his police jacket undone, which although small things, and even allowing for him having been engaged in the physical labour of digging up a grave, are a notable indicator of just how much he is unravelling.

Rather than attempting to contact the mainland for backup he seems obsessed with solving the case on his own, perhaps because if he can it will prove the continued superiority of his belief systems and authority. He takes it upon himself to set aside the law he represents and effectively carries out acts of breaking and entering as part of his investigation. This is further exacerbated when he does eventually attempt to return to the mainland and finds his seaplane inoperable, most probably due to sabotage by the islanders, after which he becomes a form of vigilante. He knocks a man unconscious in order to steal his masked costume and surreptitiously join the islanders in their May Day parade and hopefully find the missing child, who he now believes will be sacrificed in order to restore the island’s failed crops. While his actions may have a practical legal and moral basis, i.e. the protection of a child to the best of his ability, his actions seem equally those of a man who has come untethered from his own strict moral and legal code. Ironically, and perhaps in part as a form of retribution which reflects his transgressing from his own codes and also possessing a vain pride in his beliefs and authority, this untethering or abandoning becomes the final contributor to his own damnation. As a result of joining the parade he is completing a ritual being enacted by the islanders, and discovers that he has effectively been herded and lead as an unknowing participant in a complex ritualistic game they have been playing with him.

As just suggested there is a hubris, or even arrogance, to Howie and his actions. Until almost the very last moment he does not seem to be able to countenance that his position of legal authority can be defeated. However the strength of his belief in this authority rapidly, and almost instantly, seems to crumble when the islanders surround him and he realises his fate as their sacrifice, and that his authority in the face of overwhelming societal wide non-compliance is now worth little.

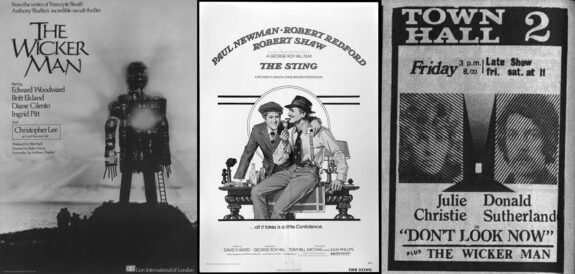

There is also a degree of hubris and possibly arrogance to the islanders’ actions. Their game playing, plotting and hoodwinking of Howie is so convoluted that it is difficult to believe they could ever think it would work, and that it did so may well be more due to chance than design. Them achieving their aims is dependant on the entire population knowing and playing their parts consistently and without constant direct supervision, and Howie also consistently responding in the desired way. In relation to this the film connects with the con artist movie genre, and has more than a little in common with the critically and commercially highly successful period film The Sting, also released in the same year as The Wicker Man, in which a large group of people work together to carry out a complex gambling related con which requires an almost absurd level of organisation, cooperation and secrecy.

(The Wicker Man and The Sting – an alternative early 1970s double bill?)

(The Wicker Man and The Sting – an alternative early 1970s double bill?)

There are also numerous other practical considerations that could have scuppered the islander’s plans, and which indicate a sense of over confidence in the islanders. For example if the weather had been particularly bad and subject to heavy downpours prior to and on the day of the parade that Howie joins as he unknowingly heads towards his doom, it is likely that the islander’s spirits would have been considerably dampened and their costumes and Lord Summerisle’s make up potentially ruined. This would have made the bizarrely upbeat and celebratory nature of their ritual sacrifice of Howie considerably less easy to achieve, while the wicker man pyre they use in this ritual would possibly not have easily burned.

The Wicker Man is ambiguous on a number of levels and it does not have easily or well defined good versus bad protagonists and sides. While nominally the “goodie” or hero, Howie is difficult to warm to or view as such, due in part to his priggish, close minded and judgemental personality, and also him having and representing a puritanical personal and societal viewpoint. Alongside which Lord Summerisle and the islanders may be acting for what they consider the collective good in sacrificing the sergeant but they are still carrying out an act of murder.

Also, despite presenting itself as being benevolently organised and ruled by Lord Summerisle and containing a contented population there is an ambiguity to the structure and society of Summerisle.

The islanders accepted and embraced Lord Summerisle’s grandfather as their ruler, and subsequently Summerisle’s father and then himself, after their lives of near starvation were drastically improved by Lord Summerisle’s grandfather who, as referred to at the start of the chapter, introduced new strains of crops which were able to flourish in the island’s unusually temperate climate. Accompanying this Lord Summerisle says that his grandfather thought that:

“the best way of… rousing the people from their apathy [was] by giving them back their joyous old gods and [by telling them that] as a result of this worship the barren island would burgeon and bring forth fruit in great abundance.”

Part of this process of worship and creating social cohesion appears to have included the introduction of the aforementioned playful religious and folkloric rituals, and an open-minded acceptance of revelry in the form of sexual freedom, communal singing and drinking. This proved a seductive and efficient mix, and caused the Christian ministers to flee, with the island’s isolation presumably allowing this way of life and beliefs to become deeply embedded.

But all this has a flipside; is Summerisle a sexually uninhibited society which has cast off puritanical strictures, or an amoral and licentiously creepy form of cult and its brainwashed victims? Or perhaps a mixture of both? Accompanying this, although not overtly, the film can also be viewed as a reflection of real world post 1960s hippie-like ideals and free love that are still “happy clappy” but which have corrupted and curdled into something darker and self-deluding.

In essence the Summerisle family’s methods of maintaining control can be seen as a variation on the classic “bread and circuses” concept, which has its origins in Roman times, i.e. the family have kept control over the island’s population through keeping them happily fed and entertained. There is considerable moral complexity and ambiguity to this, as the islanders’ lives have been materially improved and they generally seem quite happy under their benevolent patriarch’s rule, while equally their acceptance may be due to the successful embedding of an imposed belief system, rather than due to acts of free will.

Related to which for the viewer there is a potentially ambiguous and morally confusing sense of sirenish seduction to the life and world of Summerisle as presented in the film. The folkish songs on the soundtrack and which at times are performed by the islanders, in particular “Corn Riggs”, “Willow’s Song” and “Gently Johnny”, are hypnotic lullabies that linger in the memory and draw the viewer in, the islanders appear to have all their practical and spiritual needs taken care of and the island itself is a timeless rural idyll. Accompanying this the ideology and beliefs that underpin the islanders’ way of life are eloquently and logically presented by a charismatic and benevolent leader (albeit who is also slightly pompous and bufoonish), who seems to intellectually out manoeuvre and rationally refute Howie and conventional and/or Christian society’s arguments at every step. All this can create a heady mix which obscures the realities and problematic nature of Summerisle’s society, not least issues around compliance and control, and also the way it is prepared to solve problems relating to agricultural issues and social cohesion in an extreme and unhinged way (i.e. by entrapping and sacrificing an outsider).

In order for the Summerisle society to continue functioning how it does, all outside influences and contact must be kept to a minimum. Connected to which, in terms of how the islanders are kept entertained through their own homegrown forms of entertainment, such as communal singing and folk rituals, Summerisle seems removed from the rest of the world and time. Also, although there are examples of contemporary branded food, alcohol and other consumer items on the island, alongside some electrical appliances such as hairdryers in the salon, there is little evidence of contemporary electronic entertainment media. It is almost as if in some unspoken and undisclosed manner record players, radios and television have largely and quietly been kept off the island. Perhaps this was instituted by the Summerisle family for fear that they would threaten or usurp the more traditional communal forms of entertainment and ritual which bind the islanders together in their pagan beliefs. Or maybe the islanders themselves have had no need for them, preferring their own more homegrown folklore orientated entertainments. Whatever the reasons this aspect of the film can be seen as a reflection of how in the real world sections of society were drawn to traditional, rural and folkloric places and culture in the 1970s as a form of escape from the troubles of contemporary life, and as part of an attempt to find alternative or more authentic forms of experience and ways of life, which is also discussed elsewhere in the book.

To a degree watching the film is to be given a view of the last decades or corner of a particular way of life. The islanders have been able to live how they do due to their isolation, but it is unlikely that this could have been maintained indefinitely in the face of technological advancements, in particular the relentless and all conquering nature of digital technology and internet communications which would gain considerable pace within a few decades of the film’s events. However, although maintaining their isolation in future decades would have been unlikely, it would not have been impossible and such ambiguities about the film’s story and world, and the way they leave space for the imagination to wonder, may well be part of what has led to it having such an ongoing fascination:

“We don’t know if Summerisle’s sacrifice fails – the apples could come tumbling out of the trees that year, but if they don’t, the people will have to have another go next year… But if the apples do return, whether it was because of the sacrifice or by a natural process – it’s not unknown for crops to fail and grow the next year – who knows? It’s not, after all, the continuing story of Summerisle. You have to be left with a certain doubt.” (Anthony Shaffer quoted from “The Wicker Man”, Cinefantastique, as above.)

Existing alongside this sense of “doubt” about the future of Summerisle are the almost myth-like stories around the films production, which include how footage was disposed of and buried in motorway foundations and no “full” version of the film is still known to exist, which creates further imaginative space around the film:

“And this, perhaps, is the final clue to the uncanny hold it has over its admirers – the notion that, even in the longest extant cut, what we’re seeing is not The Wicker Man, not quite. Its ultimate version may never be seen – the lost movie Christopher Lee made decades ago, existing now only in scenes that haunt his memory.” (Quoted from “A Pagan Place”, as above.)

Which seems like an appropriate place to leave this “cultural behemoth”.

Elsewhere at A Year In The Country (well, a few of such things, I expect there are more):

- The Wicker Man Soundtrack and a Summer Isle Mini-Industry

- The Wicker Man – The Future Lost vessels and Artifacts of Modern Folklore

- 138 Layers and Gatherings of The Wicker Man

- Summerisle in (Sort Of) Pop #1 – Pulp’s Wickerman

- Summerisle in (Sort Of) Pop #2 – The Sneaker Pimps’ How Do / Kelli Ali’s Willow’s Song

- Your Face Here; Peering Down into the Landfill – A Now Historical Perspective on the Stories of The Wicker Man

- The Wicker Man / Don’t Look Now Double Bill and Media Disseminations from What Now Seem a Long Long Time Ago

- Constructing The Wicker Man

- The Wicker Man, Edge of Darkness and Village of the Damned – The “Tricky” Cult Remake

- Willow’s Songs

- Revisiting Willow’s Songs

- The Wicker Man Revisited / Refreshed – The Long Arm of the Lore

- The Wicker Man – Summer Isle Books, Bindings, Pounds, Shillings and Pence

- Sing Cuckoo: The Story and Influence of The Wicker Man Soundtrack and Other Partly-Archived Summerisle Discussions

- The Wicker Man – Notes on a Cultural Behemoth