First off to loosely define Brutalist architecture:

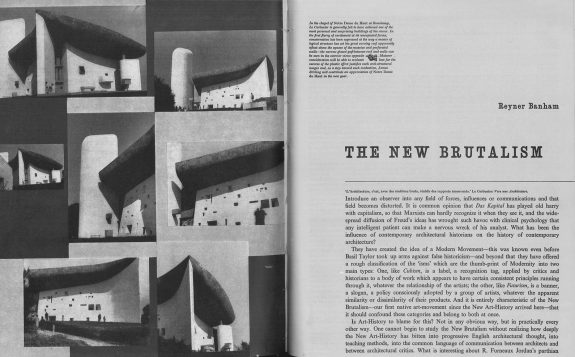

“Brutalism is an architectural style of the 1950s to approximately the mid-1970s which descended from the modernist architectural movement of the early 20th century. It is characterised by simple, often innovative block-like forms and utilised raw concrete as its primary material. Brutalist buildings often reveal the means of their construction through unfinished surfaces that bear the imprints of the moulds that shaped them. The name for the style is most commonly attributed to Swiss-French architect Le Corbusier , who specified béton brut (concrete that is raw or unfinished) in his Unité d’Habitation apartment buildings, the first of which was completed in Marseille in 1952. Architecture critic Reyner Banham spread the term more broadly through his writings on the work of British architects Alison and Peter Smithson, whose work focused on raw materiality and an industrial aesthetic.”

In his article “The New Brutalism” which architecture critic Reyner Banham wrote for The Architectural Review in 1955 he warned that “The New Brutalism eludes precise description” but listed three qualities which have come to be a starting reference for Brutalist objects and architecture:

- Memorability as an Image

- Clear exhibition of structure

- Valuation of materials for their inherent qualities “as found”.

(The above is loosely paraphrased and quoted from the Brutalist DC, Tate.org and Wikipedia websites.)

At first glance it might seem a little strange that Brutalist architecture seems to sit easily amongst “otherly pastoral” cultural interests; a point of conjunction is that both share a sense of “Fall” from an imagined or lost golden age.

With the appreciation for Brutalism this could be seen as a hauntological yearning for lost progressive futures, which relates to the architectural form’s connection to and some of its roots being in utopian socially progressive thought; in terms of post-war British social housing the intentions behind it were at times an attempt to create a solution which could provide modern high quality housing for the general populace.

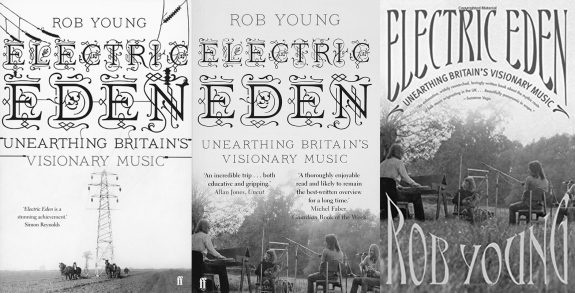

In terms of folk culture this utopian aspect connects to what author Rob Young described in his book Electric Eden as folk/visionary pastoral culture’s yearning for “folk memories of an unsullied rural state of mind which now appears like a golden age” and the way in which relics from a world before an industrial “Fall” are revered, with old buildings, texts, songs etc becoming “talismans to be treasured, as a connective chain to the past”.

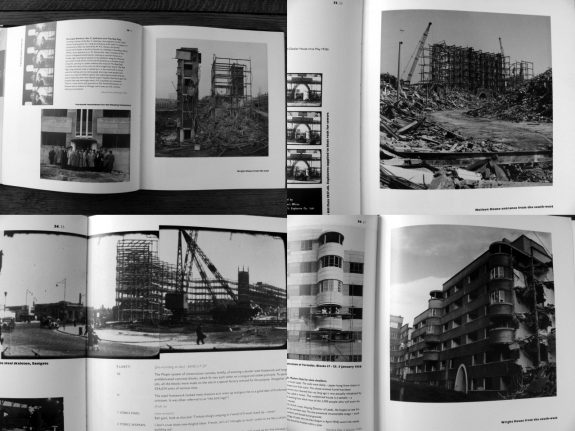

Brutalist orientated social-housing in Britain could in part be seen as a well-minded grand social experiment. Unfortunately as mentioned before at A Year In The Country when writing about Peter Mitchell’s book Memento Mori (which focused on the controversial and now demolished Quarry Hill Flats which were built in the 1930s with a progressive intent to house people in a modern manner as part of “a great social experiment” and which could be seen as an antecedent to later Brutalist estates) there often appeared to be “bugs in utopia” in terms of related housing projects. In particular, where despite the progressive intentions of those who championed and worked to create such projects, in practice a number of instances the resulting buildings it failed to provide fit homes. To a degree there seemed to be a divide or remove between “a romantic outsiders’ intellectual sense of the importance of building communities within and via large-scale, flat orientated modernist social housing projects” and the human needs and realities of those who would live there.

Some of that philosophical remove is reflected at points in an ever-growing library of books and publications, proliferation of websites, social media accounts etc which focus on an appreciation of Brutalist architecture more in an aesthetic sense and/or directly or indirectly in terms of how it represents lost progressive futures and alternative pathways society may have taken rather than its real world failures.

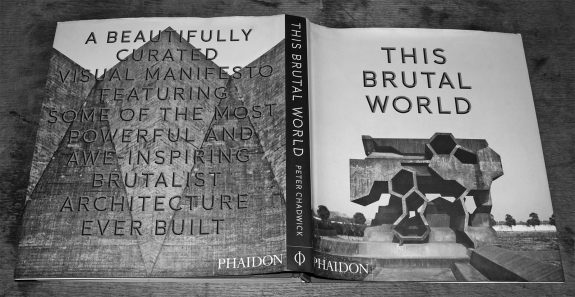

The observations in this piece on that sense of remove are not necessarily a criticism. Alongside a purely aesthetic appreciation there is often a sense within Peter Chadwick’s book This Brutal World (2016), which I discuss below, Jan Kempemaers’ images of Cold War Spomenik memorials which are collected in his 2010 book of the same name and Christopher Herwig’s 2015 book Soviet Bus Stops, of recording and honouring the remaining and caught in time but slowly fading away monuments and relics of a former age’s lost future. Many of the structures featured in such books are visually striking physical examples of relatively recent history’s striving and aspirations and taken as a whole there is space within such work for both aesthetic and more socially rooted appreciations and studies.

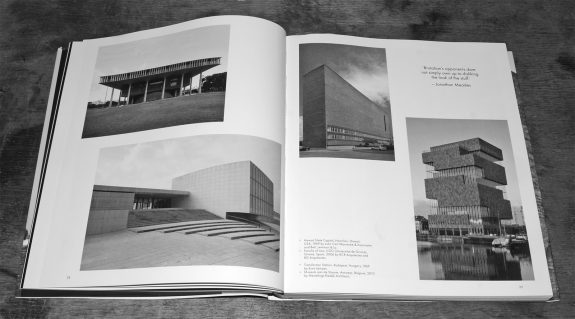

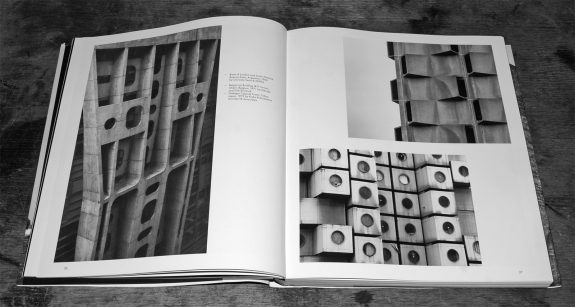

This Brutal World collects the author’s photographs on this subject which, along with his accompanying introduction, reflects his passion for and longstanding commitment to the subject. It is a handsomely produced and curated book in which Chadwick’s images portray the striking nature of many of these structures in a visually graceful and well observed manner.

It is resolutely not a study of the social disfunction and neglected aspects of some Brutalist designed social housing but rather a celebration of its aesthetic explorations. Brutalist architectural housing and residential structures are an aspect of This Brutal World, it does not focus on such projects when they have “failed” and are in a state of neglect, abandonment etc. Residential structures are also only one area amongst structures built for a multitude of purposes that are featured in the book, which take in amongst many others places of worship, water and satellite towers, monuments, a music study centre, municipal buildings etc.

Text in the book talks of the “awe-inspiring” and “once heroic, visionary” nature of such architecture and the buildings and structures are photographed and presented in a way which captures what some may consider to be their beauty; even when the skies are overcast the structures appear well lit and few of the buildings are shown marked by rain or decay. Also the photographs are all monochrome, which in this instance tends to remove the more oppressively grey aspects of concrete buildings.

As a collection This Brutal World is more orientated to being an appreciation of the aesthetic and philosophical design aspects of Brutalist architecture rather than its in part socially progressive history; related utopian aspects are acknowledged in the introductory text but the author’s writing and quotes by others which are featured in the book, alongside the aforementioned visual grace of the photographs, are more an expression of his appreciation for Brutalist buildings, monuments etc as abstract creative structures rather than as architecture which had both aesthetic and utilitarian worth. Hence he mourns the demolition of buildings which were unpopular, unsuited to their environment and poorly maintained.

Viewed today many of the structures featured in This Brutal World could be seen as a form of retro-futurism (which is a sometimes defining aspect of hauntological aesthetics and interest); they are a literal physical representation of the shape of the future’s past.

To be continued in Part 2 (which depending on when you are reading this, may not have been published yet)…

Elsewhere:

- This Brutal World

- This Brutal World at Phaidon publishers

- Peter Chadwick’s This Brutal House site

- Jan Kempemaers Spomenik

- Soviet Bus Stops

- Christopher Herwig’s Soviet Bus Stops at FUEL publishers

- The Electric Eden website

- The Electric Eden book

- Peter Mitchell’s Memento Mori at RRB PhotoBooks

Elsewhere at A Year In The Country:

- Peter Mitchell’s Memento Mori and Bugs in Utopia: Wanderings, Explorations and Signposts 35/52

- Day #229/365: A Bear’s Ghosts…

- Week #9/52: Christopher Herwig’s Soviet Bus Stops, echoes of reaching for the cosmos, folkloric breakfast adornment and other artfully pragmatic curio collectings, encasings and bindings…

- The Quietened Bunker, Waiting for the End of the World, Subterranea Britannica, Bunker Archaeology and The Delaware Road – Ghosts, Havens and Curious Repurposings Beneath our Feet: Chapter 17 Book Images

- A Bear’s Ghosts – Soviet Dreams and Lost Futures: Chapter 12 Book Images

- Electric Eden – Unearthing Britain’s Visionary Music – Folk Vs Pop, Less Harvested Cultural Landscapes and Acts of Enclosure, Old and New: Chapter 1 Book Images

- Day #4/365: Electric Eden; a researching, unearthing and drawing of lines between the stories of Britain’s visionary music