Over a number of years musician Sharron Kraus’ work has included a personal and distinctive exploration of pastoral and folk culture, and the quote below is an indication of some of its atmosphere’s and themes:

“[In the text which accompanied her 2013 album Pilgrim Chants & Pastoral Trails] there is a sense of her discovering and rediscovering the land as she had begun to live in or visit the Welsh countryside, exploring her surroundings and unlocking some kind of underlying magic or enchantment to the landscape… [the music on the album contains] a dreamlike quality that is rooted in the land but is also a journey through its hidden undercurrents and tales… Her text for the album also infers a sense that… [she was] making work which could try to interpret and/or represent the secrets in the valleys, streams and pathways through which she wandered.” (Quoted from A Year In The Country: Wandering Through Spectral Fields, 2018.)

A more recent exploration of the “magic or enchantment” and secrets of the landscape and interconnected culture which Sharron Kraus has undertaken is her Preternatural Investigations series of podcast released in 2020, that explored themes including “Magic and the Preternatural”, “The Magic of Place”, “Old Traditions and New”, “How Weird is Folk?” and “The Quality of Wildness”.

The podcasts have a calming and almost hypnotic character and although at times they wander into darker tinged territories, there is a positivity to them, and they explore some quite complex, layered theories and subject matter in an accessible manner, which is accompanied by an atmosphere and evocative use of music.

At the podcasts’ website Sharron Kraus describes them as being:

“about things that are strange but not too strange; the marvellous things that lie ‘between the mundane and the miraculous’.” (Footnote 1)

Related to which, one of the central themes of the podcasts appears to be a sense of trying to find a more balanced, less oppositional or dichotomous view of the world, its mysteries, experience, life in general etc; a way of viewing and experiencing things that is able to interconnectedly explore science, religion, nature and culture alongside the magical, mystical, preternatural, supernatural and so on.

This connects with hauntological, otherly pastoral or “wyrd” rural/folk culture in that often in such culture there seems to be a seeking and exploring of something on the edge of knowing, a layered sense of mystery and things which cannot be straightforwardly explained; a seeking out of secular magic and mystery accessed through the “portals” of culture.

This sense of culture containing some layered sense of the not fully known also interconnects with some of the topics discussed in Simon Reynolds’ article “Haunted Audio: Society of the Spectral” that was published in Wire magazine’s November 2006 issue, which was an in-depth exploration of hauntological related work around the time it had begun to coalesce as a loosely interrelated cultural grouping:

“[Hauntological] ‘ghostified’ music doesn’t quite constitute a genre, a scene, or even a network. But it is a [nebulous entity which is] more of a flavour or atmosphere than a style with boundaries… [one that perhaps] ought to elude our grasp, like mist or a mirage.”

Preternatural beliefs and interests often interconnect in various ways with new forms of technology, which Simon Reynolds also refers to in the above article:

“it could be argued that music is inherently phantasmal. Partly this is a matter of the immateriality of sound, its insubstantial and evanescent quality; the way certain melodies haunt our days whether we wish it or not; the madeleine-like capacity of certain harmonies or sound-textures to unlock our memories. Another facet to this relates to the spookiness of recording. Edison originally conceived the phonograph as a way of preserving the voices of the dearly beloved after their demise. Records have habituated us to living with ghosts. We keep company with absent presences, the immortal but dead voices of the phonographic pantheon… [while sampling can create] an uncanny friction caused by ‘different auras, different vibes, different studio atmospheres, different eras’ being placed in ghostly adjacence. If phonography has never fully shed its [original] Edisonian function… then sampling is even more unnatural: a mixture of séance and time travel.”

As also suggested by Simon Reynolds in the above article, through enabling us for the first time ever to be able to hear, manipulate and recontextualise recordings of the deceased it could be considered that newer technology still retains a sense of the mysterious, although such “spooky” aspects seem to be quickly overlooked. Similar themes and how audio and video recording devices and other media can have a time portal, preternatural or paranormal-like ability to disrupt the natural progression of time and the fading of memories were discussed by Jess Hicks in a review of science fiction author William Gibson’s collection of his non-fiction writing Distrust That Particular Flavor which was published in 2012:

“‘Time moves in one direction, memory another’, [author William Gibson writes in Distrust That Particular Flavor], ‘We are that strange species that constructs artifacts intended to counter the natural flow of forgetting.’ And because time and forgetting are natural forces, those artifacts always have the hint of the uncanny about them. Gibson notes the relative novelty of recorded music: it’s only recently that Elvis could keep crooning from beyond the grave. Yet rarely do we stop to consider this change…”

Such technologies and their abovementioned abilities are accepted as normal and commonplace, whereas the (admittedly less reliably accessible) use of a medium to do the same is not. Interconnected with which and the “phantasmal” nature of music and recording technology, in an article called “Smoke and Mirrors: Spiritualism in World War One” at the BBC’s website (Footnote 2) it is claimed that burgeoning technology around the time of the First World War played a major role in the increase in popularity of spiritualism. In the article it is said that the advent of radio and telegraphy was able to link people together during the war, and also gave people a way to understand spiritualism, with the term “tuning in” being used to describe a medium making contact with the spirit world, alongside which people would talk about the channels and wavelengths of the “other side”.

This interconnection and appropriating of terms connects with comments in the preternatural documentary orientated first series of the BBC television series Leap in the Dark (1973-1980), that water divining only seems mysterious as it cannot be explained, in a similar way that electricity would have seemed mysterious in previous centuries; one era’s witchcraft and sorcery becomes another’s scientific theory and prosaic part of reality. Such interconnecting and appropriating of terms related to spiritualism and technology as that just referred to may also be representative of a liminal or transitional point between practices and beliefs predicated on older more folklore, superstition and magic orientated ways and newer more scientific and technology orientated ones.

The connection between the paranormal, afterlife and technology seem to continue occurring through different decades, although often its expression is via fictional stories – such as when a television set acts as a portal for the ghosts of the deceased and an evil spirit in 1982 film Poltergeist, and more recently the 2006 film Pulse, where a computer virus unlocks a portal that connects the realms of the living with that of the dead – rather than as part of people’s own lives and experiences, as was the case in spiritualism’s appropriation of radio transmission terminology.

Hauntology orientated work’s exploration and conjuring of the spectres of half-remembered or misremembered memories, parallel worlds, “the past inside the present” and often eerie or unsettling atmospheres could be considered to be loosely connected to such themes, albeit in a less directly preter or supernatural manner:

“[Hauntology at times uses and foregrounds] recording medium noise and imperfections, such as the crackle and hiss of vinyl, tape wobble and so on that calls attention to the decaying nature of older analogue mediums and which can be used to create a sense of time out of joint and edge memories of previous eras… It [reimagines and misremembers past decade’s culture] to create forms of music and culture that seem familiar, comforting and also often unsettling and not a little eerie; work that is accompanied by a sense of being haunted by spectres of its, and our, cultural past…” (Quoted from A Year In The Country: Straying From The Pathways)

Hauntology and wyrd rural/folk culture’s exploration and searching for a form of “otherlyness” and “something on the edge of knowing, a layered sense of mystery and things which cannot be straightforwardly explained” could be considered to be a variation on another loosely interconnected area or mode of culture, that of magic realism orientated literature, film etc. In these areas of work, realistic or even mundane views of the modern world are presented, accompanied by magical elements that often are merely an accepted and day-to-day but unexplained part of their fictional worlds.

Hauntological, wyrd rural/folk work, and Sharron Kraus’ thematically interconnected Preternatural Investigations podcast, could also be considered at times to be a variation or exploration of the preternatural, the unknown etc that sidesteps some of the preconceptions and baggage which such things can carry with them. This is an aspect of related work which writer and academic Robert Macfarlane has discussed when he suggested that:

“It would be easy to dismiss [such work] as an excess of hokey woo-woo; a surge of something-in-the-woodshed rustic gothic. But engaging with the eerie emphatically doesn’t mean believing in ghosts. Few of the practitioners… would endorse earth mysteries or ectoplasm. What is under way, across a broad spectrum of culture, is an attempt to account for the turbulence of England in the era of late capitalism. The supernatural and paranormal have always been means of figuring powers that cannot otherwise find visible expression. Contemporary anxieties and dissents are… being reassembled and re-presented as spectres, shadows or monsters: our noun monster, indeed, shares an etymology with our verb to demonstrate, meaning to show or reveal (with a largely lost sense of omen or portent).” (Quoted from “The eeriness of the English countryside”, Robert Macfarlane, www.theguardian.com, 10th April 2015.)

A (fairly) recent example in cinema of attempting to update explorations of the preter and supernatural can be found in Oliver Assayas’ film Personal Shopper (2016), which explores and offers a nuanced and layered subtle contemporary take on the preter/supernatural and ghost stories. Its story provides an alternative to more conventional paranormal orientated work and tropes and, as is often the case in magic realist orientated work, there is an acceptance of the preternatural as just being merely another part of the day-to-day world and there is little discussion or debate of its veracity or of those who claim to be able to connect or communicate with it.

In Assayas’ film the central character is a woman called Kyra who is in her twenties, played by Kristen Stewart, and who works as a high fashion personal shopper for a wealthy celebrity. It is mostly set in the built-up centres of the capital cities London and Paris, although it opens in an area which may be the suburbs of Paris but that due to it having a leafy autumnal bucolic appearance which is backgrounded by hills and fields could equally be a smallish rural town. It is here that Kyra spends the night in the house where her brother lived and has her first brief encounter, in the film at least, with some form of preternatural or spirit presence.

Kyra has stayed the night in the mansion as, somewhat contrastingly with her work as a personal shopper, she also acts as a medium, including in this instance for a couple who knew and loved her late brother and wish to find out if her brother’s former home has spirits, whether benevolent or malevolent, before they buy it, and while there she also attempts to contact her deceased brother’s spirit.

There is a sense of Kyra putting her life on hold and she describes herself as just waiting, with her existence being defined by and centring around a wealthier “other”. There is also an interrelated accompanying sense that the resultant possible squandering of ability and potential, and the subsequent emotional fallout of the related frustration and dissatisfaction, has been redirected to become a source for the creation of externally manifested psychic spectres or wraiths and preter or supernatural phenomena.

During the film Kyra experiences paranormal phenomena that she initially assumes are spirits, or her brother attempting to contact her. However the film ends on a variation of séance-like table rapping carried out by her, and when she asks an apparently visiting spirit to tell her if it is her brother there is only silence but it knocks just once to signal yes when she asks “Or is it just me?”

In one sequence during Personal Shopper there is an intertwining of the supernatural and modern prosaic seeming but actually very advanced high-tech digital technology when Kyra receives a barrage of text messages on her smartphone sent by some unknown person, or thing, which is perhaps the spirit of her brother. Related to this and the film’s intertwining of day-to-day reality and the supernatural, Oliver Assayas spoke in an interview for the MUBI website of how Personal Shopper was influenced, in part, by his interest in 19th century spirit photography, with him going on to say that:

“I like the idea of the two parallel narratives: to have on one side the very documentary reconstruction of the [central character’s] London trip; and on the completely invisible level this conversation with ‘something’, someone that’s not there. I like the idea of communicating with something that’s invisible, that’s mysterious, that’s not completely elucidated… We never know who actually, where that person is… Which ultimately connects somehow with the spiritualism, in the sense that the birth of spiritualism, the origins, in the mid-19th century has to do with all the incredible inventions that were happening at the same time. And which gave a sense of making possible things that had always seemed part of the magical world. To see something that’s far; to hear someone who’s not there. It gave some kind of legitimacy to the whole idea of communicating with ghosts. The spiritualism is very close to the technical avant-garde movement of the time.” (Oliver Assayas quoted from “The Process of Dreaming: Oliver Assayas Discusses Personal Shopper”, Daniel Kasman, www.mubi.com, 6th October 2016.)

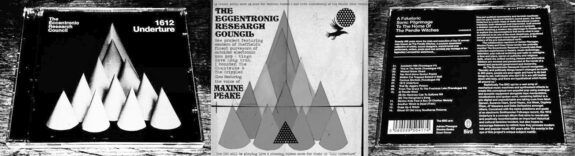

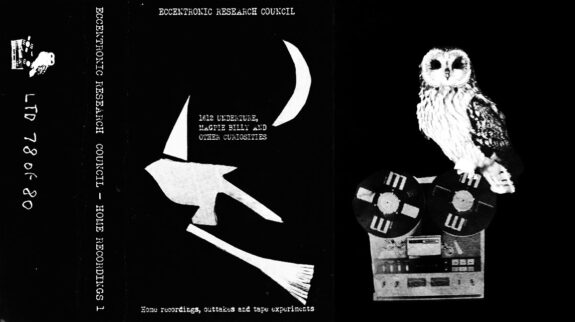

Which in turn, as a final point, makes me think of how The Eccentronic Research Council suggest on their Finders Keepers Records released album 1612 Underture (2012) – which was described in text which accompanied its release as “A fakeloric sonic pilgrimage to the home of the Pendle witches” – that mobile phone handsets and their uses are a form of “modern-day magic on a monthly tariff”.

Footnotes:

- The quoted phrase in the description is taken from lorraine Daston and Katharine Park’s book Wonders and the Order of Nature, 1150-1750 (1998).

- “Smoke and Mirrors: Spiritualism in World War One”, author unknown, Home Front, bbc.co.uk, date unknown.

Links elsewhere:

- Sharron Kraus’ main site

- Sharron Kraus’ Preternatural Investigations

- Sharron Kraus’ Pilgrim Chants & Pastoral Trails

- Simon Reynold’s blissblog site

- Simon Reynold’s Retromania site

- Wire issue 273 (featuring Simon Reynolds “Haunted Audio” article)

- The Personal Shopper trailer

- The Criterion Collection edition of Personal Shopper

- “The Process of Dreaming: Oliver Assayas Discusses Personal Shopper” article at mubi.com

- “Smoke and Mirrors: Spiritualism in World War One” article at the BBC’s site

- Robert Macfarlane’s “The eeriness of the English countryside” article

- The Eccentronic Research Council’s 1612 Underture album at Finders Keepers Records’ site

- The Eccentronic Research Council’s Bandcamp page

Elsewhere at A Year In The Country:

- Sharron Kraus, the less well trodden paths of Heretics Folk Club and unfurling sails…

- Lullabies for the land and a pastoral magicbox by Ms Sharron Krauss

- Pilgrim Chants & Pastoral Trails, From Gardens Where We Feel Secure and Wintersongs – Lullabies for the Land and Gently Darkened Undercurrents

- Sharron Kraus’ Right Wantonly A-Mumming

- Simon Reynold’s Exploration of Haunted Audio: Spectres vs Retro

- Alan Garner’s “To Kill a King” Episode of Leap in the Dark and Tales from a Deeply Layered Past

- A Definition of Hauntology – Its Recurring Themes and its Confluence and Intertwining with Otherly Folk

- Robert Macfarlane, Benjamin Myers, The Eerie Landscape and Unravelling of Dizzying Mazes

- Sapphire & Steel and Ghosts in the Machine – Nowhere, Forever and Lost Spaces within Cultural Circuitry

- Sapphire & Steel, various ghosts in the machine and a revisiting of broken circuits…

- Sapphire and Steel; a haunting by the haunting and a denial of tales of stopping the waves of history…

- The Eccentronic Research Council: modern day magic on a monthly tariff and the rhyming (and non-rhyming) couplets of non-populist pop

- Magpahi, Paper Dollhouse and the Eccentronic Research Council – Finders Keepers/Bird Records Nestings and Considerations of Modern Day Magic