Category: Unfiled

Arboreal Explorations 24

The White Reinder – A Folk Horror Precursor Under a Leaden Sky

The White Reindeer (1952) was the first film made by Finnish cinematographer Erik Blomberg. It is set amongst the bleakly beautiful snowbound landscape of Finnish Lapland and tells the story of a newly married young woman called Pirita who becomes lonely, frustrated and desperate for affection due to her husband often being away herding reindeer, which leads her to seek out a shaman who gives her a potion which will make her desirable to all men.

However, this leads to deadly consequences as the magic powers she gains are beyond her control and cause her to become a vampiric shapeshifter who can assume the form of a white reindeer, which she does in order to lure male herders out to isolated spots where she then kills and consumes them.

It’s a strange experience watching a horror film when you know that there are unlikely to be any graphic scenes of any kind due to such things generally being neither the norm nor allowed due to censorship and societal expectations at the time when it was made. Even with knowing that when watching The White Reindeer, I still found myself tensing and expecting all of a sudden beasts, gore, fangs, etc, to jump out of the screen.

Despite this lack of more graphic visual shock, etc, the film still has a distinctly unsettling atmosphere, perhaps in part because of the way it initially lulls the viewer into a false sense of security and seems almost like a family-friendly period documentary, with the early scenes showing Pirita and the other villagers in their traditional Finnish clothes carefreely frolicking in the snow and good-heartedly racing one another on reindeer-drawn sledges.

But The White Reindeer is soon revealed to be far removed from being a period romp rather, it shares a number of similarities with John Carpenter’s science fiction horror classic The Thing (1982), with both showing an isolated group of people in a bleak snowbound landscape who must try to identify and fight a deadly being that is able to hide amongst them by taking on human form. However, rather than being a straightforward genre film, Blomberg’s film has a dream and almost fairy tale-like quality and is nearer to being a form or precursor of arthouse horror.

As the film progresses, almost without the viewer realising, the atmosphere and tone become ever darker, particularly after a notably folk horror-like sequence where, in order to “activate” her potion, Pirita is required to sacrifice a young fawn to a stone god, the physical marker for which is a tall standing stone that is be topped with the skull and antlers of a reindeer and is sited amongst a sacrificial graveyard of antlers. She then goes on to claim victim after victim in the snow-filled landscape, which, rather than being crisp and brightly white, is more often shown in various shades of grey under a leaden sky.

Initially, it appears as though Pirita has little control or volition over her transformations and deadly actions, and it seems as though she may not even be all that aware of them when she is her “normal” self. Alongside which, she seems to have been damned from birth as a haunting opening song tells of a woman, presumably Pirita, who unbeknownst to her was born a witch with “evil in her belly” and indicating this, even before she has taken the potion, she is shown leering menacingly over the shaman, apparently uncontrollably revealing her inner “witch”.

These aspects, combined with her siren-like supernatural deadly irresistibility and taking the form of a reindeer when she is entrapping her male victims, could be seen as an exploration and expression of masculine and societal fear regarding unfettered, animalistic female sexuality and its power over men. This is given further expression when once Pirita has given in to and used her power, she then seemingly becomes beyond redemption. Despite her desperate attempts to reverse the magic curse when she comes to realise what has happened to her and sees the villagers arming themselves and preparing to hunt down the “evil” white reindeer, her fate seems sealed.

The ending is particularly poignant and bleak, as it is her husband, who does not yet know what has happened to his wife nor that he is actually hunting his spouse, who is shown singlehandedly tracking her down in a snowy valley while she is in the form of the white reindeer. He kills her with the “cold iron” of a spear and, for a brief moment, is shown as being joyously happy at, presumably, both his success and also returning safety and the status quo to the villager’s way of life.

However, his joy in this is very short-lived as on her death, Pirita has regained her human form, and she is shown impaled against the snow, and he realises what he has done and lost. The camera then pulls away to show just how isolated and alone they both are amongst the snowbound landscape. While the end song plays, the screen goes dark, but the film continues to roll almost interminably, causing the viewer to hope beyond hope that there will be another final act and that somehow things will turn out okay. But they don’t and, for Pirita and her husband, at the very least, never can.

Arboreal Explorations 23

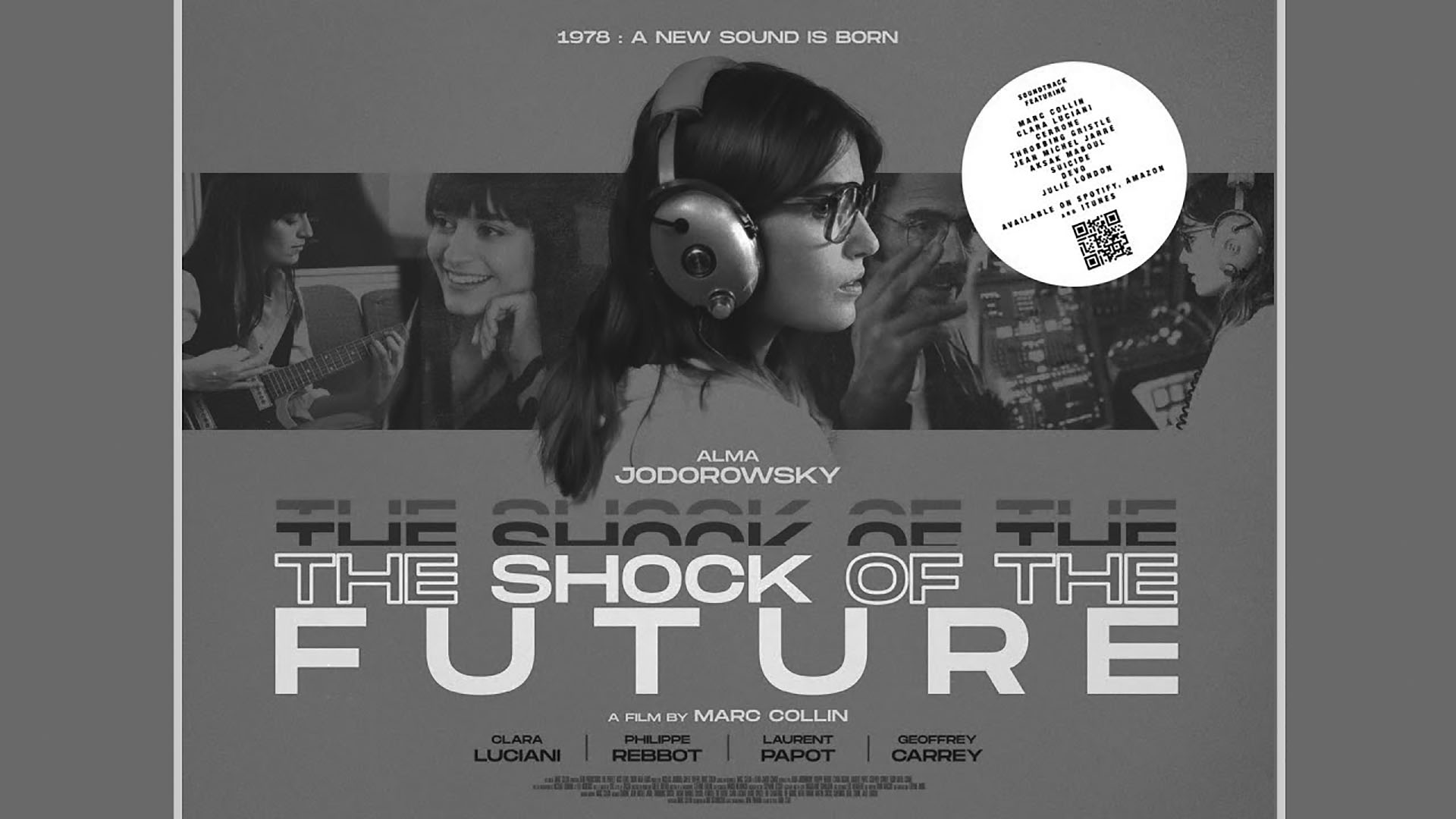

The Shock of the Future and Explorations of New Electronic Worlds

The Shock of the Future, aka Le Choc Du Futur, is a 2009 French language film set in 1978 which is centred around the birth of electro-pop and a female electronic musician called Ana, who creates related music. It was written, directed and part scored by Marc Collin, who is best known as the co-founder of the band Nouvelle Vague, which released covers of new wave, punk, etc songs in a bossa nova style (think Astrud Gilberto singing a breezy version of a Joy Division in the 1960s and you’re not a million miles off).

The film was intended in part as a tribute to the sometimes unsung or overshadowed female pioneers in electronic music, including, amongst others, Delia Derbyshire, Daphne Oram, Laurie Spiegel, Suzanne Ciani and Elaine Radique, who are namechecked in a dedication at the end of the film. Accompanying this, it could be seen as a love letter to analogue synthesisers and older physical media formats, which seem at times to fill almost every nook, cranny and corner of Ana’s flat and are shot and portrayed at points with an almost fetishistic affection and perhaps even reverence. Although perhaps due to some form of licensing issues, this appreciation of physical media formats is further added to by, at the time of writing and in the UK, The Shock of the Future has not been released digitally and can only be watched via a limited-edition DVD which is available exclusively at 606 Distribution’s website.

A press quote on the back cover of the DVD describes the film as having “a near-numinous belief in the transformative power of music”, i.e., a near-religious or spiritual belief in such things, but that belief seems to be reflected in the film more in or through the process of creating music along with an accompanying sense of discovering new sounds, ways of making music etc, related technological innovations etc rather than the actual music which is created. In turn, its title refers to the main character Ana seeing the electronic and synthesizer-led future of music and its creation and the shock and change this will cause, which although she seems to embrace it, is resisted by some of those in the music industry who she meets.

At one point she makes an impassioned near rant about this coming future and its new way of doing things during which she says there will and needs to be a rejection of the current way of taking music to audiences such as in “beer and piss stinking” rock music venues and instead it will be taken out to and performed in beautiful places amongst nature and feature music made by machines, dancing robots, beams of light, lasers etc.

In this speech, she seems to foretell the widespread uptake and popularity of electronic music in outdoor raves and also the work of some of its high-profile commercially successful French practitioners including the composer Jean-Michel Jarre whose live performances have featured him playing synthesisers by manipulating beams of light and the robot personas that the electronic music duo Daft Punk adopted.

Ana is shown having to deal with a succession of men involved in the music industry who variously lech over her and/or don’t understand or belittle her work and abilities, although equally there are a number of male characters who do respect and support her and her work.

She herself is not a character who is always sympathetically portrayed, although it is difficult to know if this was the intention in the film or whether she is intended to be shown as being merely highly focused, driven and passionate about her “cause” and work. She seems to expect everybody else to support her financially, doesn’t create the music for a commercial which she has already received part payment for and generally acts like a self-absorbed “creative” or artist who just wants to make music without involving herself in any of the less “fun” practicalities of putting her music out into the world nor supporting herself while she does so.

Filmed on location, the film is largely a chamber piece and is mostly set in the flat where Ana has been living and uses, with his permission, the real-world tenant of the flat’s collectable and expensive analogue synthesisers, sequencer etc. The curtains in the flat remain drawn throughout the film and it is as though it is a place which is both separate from and holds the real world at bay, with some of the only other fairly briefly seen locations being a windowless recording studio and the streets of Paris. The latter of these are shot with a narrow depth of field that blurs their backgrounds, possibly in part to obscure any signs of the modern world but it also has the effect of showing Ana, whose only focus and topic of conversation during these scenes are her music, and/ or her companion as still being in an almost dreamscape enclosed world where the only thing that matters is, again, her music.

This sense of Ana escaping from the real world via a pure form of “new” electronic music is heightened when a passionate older music collector visits her with a selection of the electronic and experimental music that he intends to bring to her party later, all of which are records which had real-world releases. He plays her a selection from these which she’s mostly impressed by, though she doesn’t like iconic synthesiser duo Suicide’s music and its then pioneering and radical darkly visioned reimagining of rock music via electronics and dismisses it as being too rock and too fifties. This implies a certain blinkered attitude in her which is so focused on the “new” ways of making and styles of music that she rejects all that has gone before.

Accompanying this, when the collector tries to get her to appreciate Suicide’s music by saying listen to the lyrics and that they’re about life she responds that if she wants to know about life, she’ll watch the news. The lyrics, which Ana greatly appreciates, to the electro-pop song she subsequently records with a female vocalist who has written them have a dreamlike almost abstractly ambiguous distance and meaning to them.

Further reflecting and layering the film’s creation and presentation of a world unto itself, as in part referred to above, the scenes in Ana’s flat were shot in the real-world flat of a vintage synth collector, which in the booklet that accompanies the 606 Distribution DVD release Marc Collin says that they didn’t need to move things around in the flat much at all nor redo the décor in a period style as the collector essentially still:

“lives in the 1970s… [and] he already had the [period] turntables, speakers, wallpaper… He just had to hide his CDs!”

The translation in the English subtitles for the film are quite often a little off and so “synthesisers” becomes “synthetizors”, “on mushrooms” becomes “under mushrooms” and so on. This adds a certain charm and additional layering to the film, including during a scene where a more famous and successful female musician is shown recording an electro-pop-esque song with a hybrid of traditional and electronic instruments and musicians and the slightly off translation of lyrics of the song appear, rather than being mistranslated, to be deliberately clunkily stylised which in turn brings to mind similar deliberate aspects in electroclash related music from the early 2000s, a genre and subculture which in part drew inspiration from early electro-pop.

The film ends with Ana suddenly “Having to get back to work” after refinding her inspiration and the final scene shows her sat at the bank of synthesisers in the flat playing one of the keyboards, seemingly content to once again be lost in her explorations of these new electronic worlds and soundscapes.

This in turn connects with comments by electronic instrument designer Bob Moog that when he created his pioneering iconic Moog synthesiser that:

“I think it would be egotistical of me to say that I thought of it… what happened was, I opened my mind up and the idea came through me and into my head… It’s something between discovering and witnessing.”

Links Elsewhere:

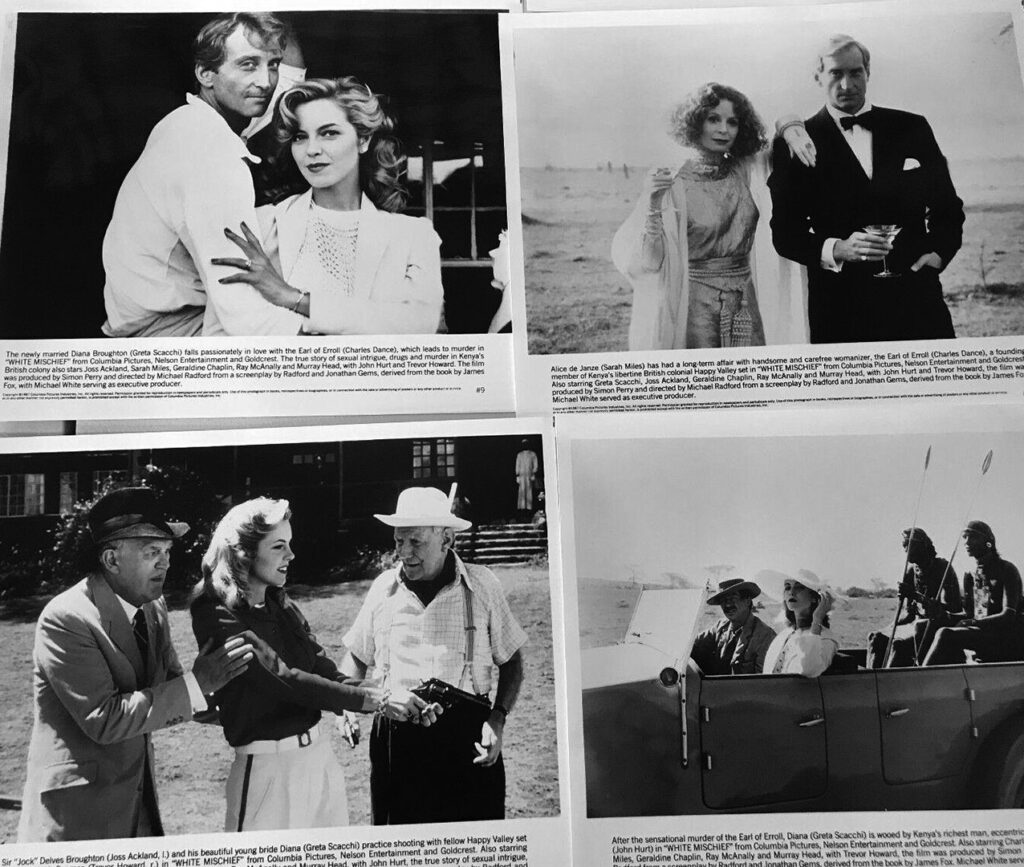

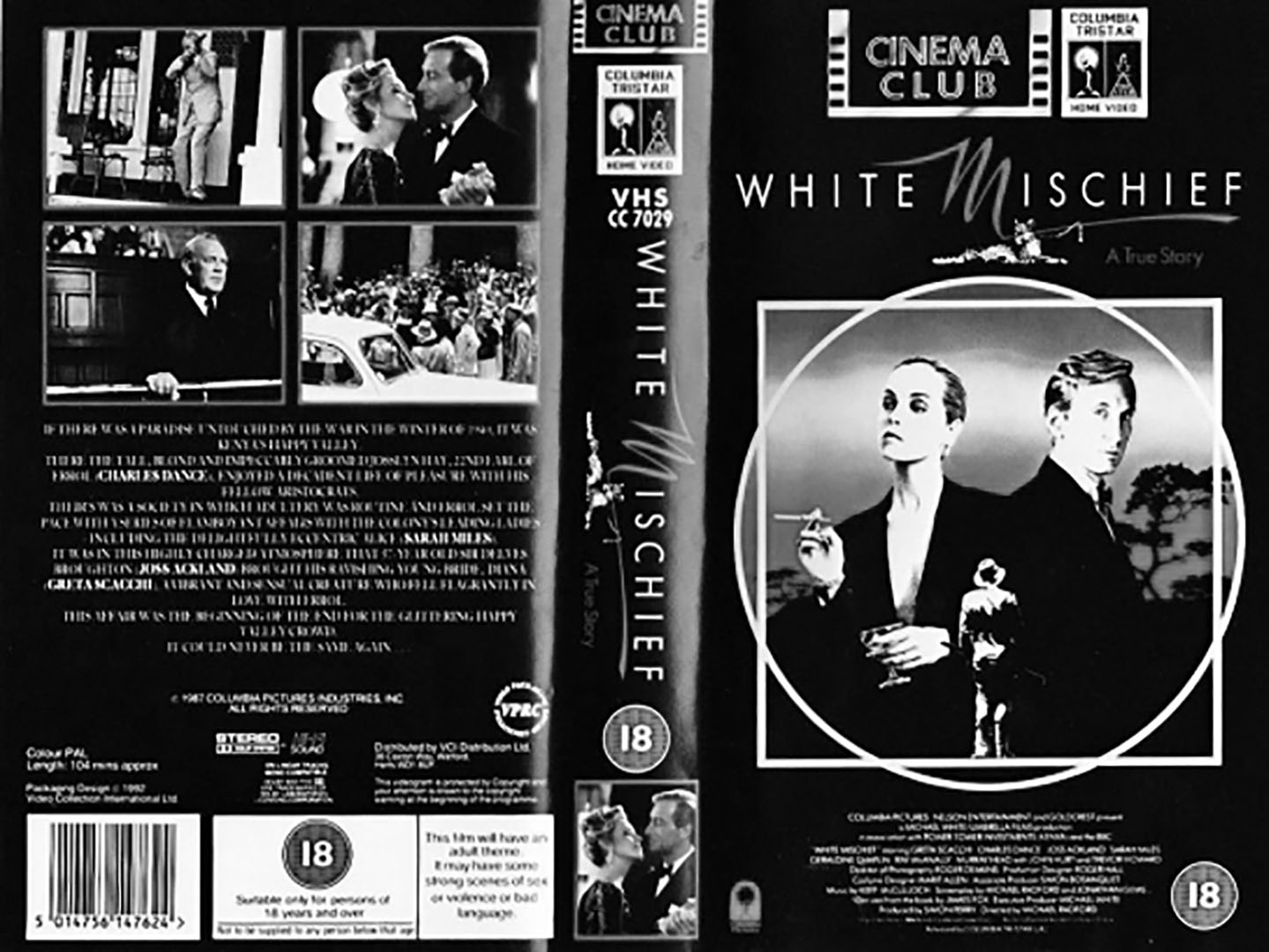

White Mischief and Dissolution Under the Sun

The 1987 film White Mischief is a fictionalised reimagining of true events that took place in Kenya during the early years of the Second World War and centres around a decadent and dissolute group of British ex-pats who are living the high life while back home people suffer the Blitz and rationing. A 57-year-old British aristocrat and his young beautiful wife enter this social world and whirl, where his wife meets and falls for a dashing, caddish and penniless aristocrat nearer to her own age, with the resulting fallout and jealousies leading to a murder which became a high-profile scandal.

It features an almost ridiculously starry British and international cast a number of who before, at the time and after have been very high-profile actors including Greta Scacchi, Sarah Miles, John Hurt Charles Dance, Hugh Grant, Trevor Howard, Murray Head, Gregor Fisher, Ray McNally, Susan Harker, Susan Fleetwood, Joss Ackland and Jacqueline Pearce who have appeared in all kinds of A Year In The Country favourites from the overlooked exploration of class boundaries The Hireling to Stephen Poliakoff’s intriguing secret state cycle conspiracy thriller Hidden City and the urban edgelands black comedy of No Surrender and, well… 1984, Ultraviolet, The Black Windmill, Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy, The Family Way, Blake’s 7, Scandal, Sapphire and Steel audio dramas etc etc etc.

Many of the ex-pats are wealthy, or live as though they still are, and their lives appear to be a constant round of drinking, gossiping, affairs and an almost childlike level of pampered luxury and self-indulgence. However, their “japes” and “jollies” don’t actually seem all that fun filled but rather a desperate empty way of trying to fill the days.

Their way of life and its dissolute nature brings to mind many of the young men and women’s lives in the LA set films Less Than Zero (1987) and The Informers (2008), both of which are adaptations of Bret Easton Ellis’s 1980s set novels, and in which despite, or perhaps because of material privilege, the characters have tumbled almost willingly into a dissolute existence that lacks any form of direction or moral compass.

White Mischief and the lives of its characters also seem to interconnect, echo and have parallels with those in the 1989 film Scandal, which focused on historic events that occurred as part of the Profumo Affair in the early 1960s, which was another high-profile scandal that involved British aristocrats, lusts, decadence and death.

Another aspect that all of these films share is that their often-tragic events are set against and contrast with a variously stylish, seductive and/or ravishingly beautiful backdrop of locations, outfits etc. White Mischief however is distinctive in that it takes such tales of dissolution away from their more common urban settings and transplants them to the African landscape, which is often described in the film as being a paradise but is actually nearer to a self-built form of purgatory where its inhabitants are (almost) forever caught in a dissolute stasis.

Arboreal Explorations 21

Rainy Day Women – An Unknown World Set Amongst a Ghost Story Without Ghosts

“That summer the countryside had suddenly become an unknown world. A ghost story without the ghosts but they were expected any minute.”

Rainy Day Women (1984), written by David Pirie, was one of the later episodes of the BBC’s Play for Today television anthology drama strand and blimey, it’s stunning, thought provoking, unsettling, shocking and at points politically radical stuff. Viewed today it’s almost difficult to comprehend that challenging work like this was once part of the everyday mainstream television landscape.

Set during the Blitz in the Second World War, its main location is an isolated and classically British bucolic (in appearance at least) village where an army officer who is suffering from shellshock/PTSD is sent to investigate rumours of a German spy.

While having its own character the drama recalls the likes of Witchfinder General (1968), Straw Dogs (1971) and The Wicker Man (1973) in the way it deals with the fear and persecution of women, the distrust of outsiders who have come to a small rural community, an outsider in a position of authority who is removed from the source of his power and subequently finds it neutered and the escalation of tensions into violent mob rule.

The few men who remain in the village have become drunk with the power that their position as Home Guards and the guns that go with it provide, and rather than seeming like patriots who wish to defend their country against invasion and the enemy within, they have become bullying jobsworths… and then much worse. Also their fears, worries and hatred of potential German spies does not seem so much an expression of patriotism but rather to be a form of moral panic and folk devils. This is particularly so as its expression finds focus and release in their persecution of a local independently minded, politically progressive and cultured woman who threatens their traditional male authority and associated expected social norms; that her husband had been interned due to being German seems more like a convenient excuse which enables the Home Guard’s persecution of her rather than the actual cause of their suspicions.

The incomer Land Girls who have come to work on the local farms due to the men going off to war have been billetted with this woman in her isolated home and there are rumours of sexual “deviancy” and a seemingly ever present undercurrent of fear amongst the men with regards to female emancipation and an accompanying worry that the woman will “turn” or corrupt the Land Girls and this will lead to an ending of their acquiescence to the men and disrupt the social hierarchy.

In the eyes of the local men, these are all qualities that mark the woman out as somebody to be mistrusted and she is known as a “witch” and thought to most probably be a spy, and when their suspicions, paranoia and perceived threats to their positions of masculine authority grow this leads to a deadly denouement. This is subsequently covered up and the story ends with a sense that those responsible for the nation’s internal propaganda during the war were willing to do whatever it took to prevent threats to morale.

The drama can be loosely placed alongside work which has been labelled as folk horror, in particular due to the way that it depicts rural areas as isolated places where the norms and conventions that govern and restrict society, individuals and behaviour are able to fall away. Accompanying this there is the push and pull contrast that is often found in folk horror between the rural location’s sun drenched bucolic beauty and the immediate and ever growing sense of threat and moral disintegration. Intertwining with this is the way that the quality of the unofficially distributed online streamable version – which as I discuss below is currently the only more easily available version which can be viewed – is considerably degraded, and this lends a darkened, grimey air and atmosphere to the village and goings on there.

At the time of writing Rainy Day Women is only available for private viewing as part of the BFI National Archive at one of five Mediatheque centres in the UK,* more widely via unofficially distributed DVDs and also unofficially through having been posted online at public video streaming platforms such as YouTube. Perhaps that will have changed by the time this is published, as the BFI is releasing restored versions of some of the Play for Today dramas on Blu-ray and some have been released to be bought officially and/or rented via online streaming. In the meantime the way Rainy Day Women has been made available to stream online and via DVD forms part of an unsanctioned folk distribution of older television programmes:

“Although these are not officially sanctioned releases, curiously considering them often being posted on high profile online public platforms the copyright holders seem to not know of or overlook them, or at least they do not appear to rigorously seek them being removed. Perhaps they do not have the resources to do this, or do not focus on the unauthorised distribution of these sometimes semi-forgotten programmes but rather direct their attention and resources towards higher profile and more in demand content. Whatever the reason, this overlooking could be considered to make their distribution not so much a form of forbidden samizdat-like publication but rather a form of archival folk preserving and distribution of culture that, while unsanctioned, acts as a substitute for official releases.” (Quoted from A Year In The Country: Cathode Ray and Celluloid Hinterlands.)

It seems a shame that so much of British mainstream archival television is only being made available in a piecemeal manner and/or its audiences restricted due to the manner of distribution and/or the related costs to potential viewers. In the case of Play for Today to watch the officially available episodes can require the purchase of Blu-ray boxsets which are not all that cheap as they can cost £40 or more each and/or there is a mishmash of some episodes being available to purchase for online streaming in the UK at Amazon while in October 2020 they were made available to stream in the US via the subscription service BritBox but are not available to view at their original home via the BBC’s iPlayer streaming service, which the majority of British homes have access to through paying for a TV license. This becomes even more convoluted as none of them are available at the BFI Player streaming service, despite them releasing the Blu-ray boxsets, while the boxsets largely have different episodes to those available to stream at Amazon, which again differ in part from those available at BritBox in the US (Are you keeping up? There will be a test later…)

This contrasts with the manner in which when the Plays for Today were first broadcast between 1970 and 1984 on mainstream television (which is all there really was at the time due to there only being a few British television channels) it was to a large and potentially diverse audience.

The ease of distribution that online streaming could potentially allow with regards to British archival television seems to still be curiously somewhat under utilised. The just mentioned subscription model streaming service BritBox, the catalogue for which largely consists of pre-existing and older British television, could potentially have provided a relatively affordably priced home for such things but seems to largely have not focused on such things but more, athough not exclusively, tends to concentrate on higher profile well known “hits” etc. While the also just mentioned BBC iPlayer also tends to concentrate on the more populist “hits” and/or more recently broadcast programmes and to largely overlook the BBC’s older archival material such as Play for Today.

All of which leads me to a post from 20th October 2020 called “Folk horror and Play for Today, the ‘National Theatre of the airwaves'” by William Fowler at the BFI’s site, which is where I discovered about Rainy Day Women, and in which he wrote:

“Analogue broadcast television is truly still the undiscovered country, countless artefacts lying in wait to be overturned by the plough… There are countless oddities and genre hybrids, folk horror and otherwise, to discover across the huge, unlikely vistas of British TV land, including but also going far beyond Play for Today. Large and unwieldy, the dales and dark woodland of this landmass are at least partially fenced in with the ceasing of the analogue signal in 2012. Or earlier still with the 1990 Broadcasting Act, which opened up the bandwidth, coaxing what would become Sky television into existence and increasing the levels of now overt competition between the channels… From that point on, it was less likely that strange things, even politically pertinent and radical things, might occupy a primetime mainstream platform… [The best of Play for Today] still say something about the lie of the land. They are all plays for today: slippery, open to different contexts, and ready for resurrection.”

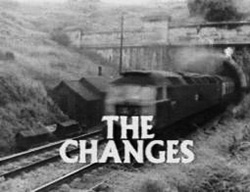

As suggested in the above quote, Rainy Day Women was produced towards the end of a period when there was space in British mainstream television for “strange… and radical things”, which had previously allowed for the production and broadcasting of the likes of challenging work that included The Owl Service (1968), Penda’s Fen (1974), The Changes (1975) and Stargazy on Zummerdown (1978):

“[such work] could be seen to indicate how during the… [1970s] the experimentation and liberalism within society and culture that occurred during the late 1960s and into the 1970s had come to also be present to a degree in institutions such as the BBC…” (Quoted from A Year In The Country: Cathode Ray and Celluloid Hinterlands, as above.)

Andy Beckett and Roger Luckhurst suggested in The Disruption (2017), a booklet that featured a conversation between them on the just mentioned television series The Changes, that this had the result of “permitting experiments and allowing the pushing of boundaries here and there…”

The peak for this “boundary pushing” may well have been during the 1970s but to a degree examples of it, including Rainy Day Women, can also be found in the 1980s, albeit in an increasingly embattled manner:

“[The 1980s could perhaps] be seen as having been part of a golden age in British television drama, which was given space to take risks and provide its audiences with [television drama] that was challenging, dealt with sometimes contentious issues but which also entertained… notable series to do so from this period might include the likes of Dennis Potter’s The Singing Detective (1986), Alan Bleasdale’s The Monocled Mutineer (1986) and Troy Kennedy Martin’s Edge of Darkness(1985)… [and A Very Peculiar Practice (1986-1988]. In some ways, such work can now be seen as flashes of rearguard resistance to a sea-change in society and broadcasting culture brought about by the increasing dominance of free market economics and an ascendant right-leaning political philosophy…” (Quoted from A Year In The Country: Straying From The Pathways, 2018.)

This “sea-change” lead academic and author Mark Fisher to write that:

“The conditions for this kind of visionary public broadcasting would disappear during the 1980s, as the British media became taken over by what… television auteur Dennis Potter would call the ‘occupying powers’ of neoliberalism’.” (Quoted from Ghosts of My Life, Mark Fisher, 2013.)

With this in mind, watching a degraded quality copy of Rainy Day Women in the current television landscape which is obsessed with ever higher resolution and sharper reproduction can seem a little like being given a portal viewing of the spectres or wraiths not just of past television drama but also of a now very distant seeming societal mindset.

*I think this is the only way of watching it as part of the BFI’s National Archive, as trying to track down the options for viewing the items they hold can be a touch “convoluted” shall we say (!)

Arboreal Explorations 20

Takashi Doscher’s Still – Explorations of Southern Gothic / Wyrd Americana and Eternal Cycles

Within culture which could be loosely labelled as Southern Gothic or Gothic Americana there is often a mythical take on the American South which has parallels with work in the UK that has come to be labelled as wyrd, otherly pastoral or weird Albion-esque. Both often have deep roots in the land and folklore, which is accompanied by a sense of the landcape being layered with hidden or unknown stories, which can be personal, spiritual, historic, geographic, fantastical, paranormal or a mixture of these and more in character.

Both wyrd and Southern Gothic etc work often features rural locations, which at times are shown as being unregulated, untamed and sometimes overlooked places, where the old ways persist. These places become psychic edgelands on the fringes of civilisation, in which the modern world has not quite yet taken hold, and where the norms, laws and regulations of conventional society do not fully apply, have been cast aside or are not abided by. Also they often portray rural areas, and sometimes their populations, as the “other”, as being separate from and unknowable to the urban and city based, and can also at times contain a sense of threat.

Some work which has been labelled as Southern Gothic can be viewed as both a critique of modernity, and also as providing space to explore social issues and reveal the cultural character of the American South. Although generally not strictly fantastical, there is often a magic realist element to this work and “a tension between realistic and supernatural elements” (Marshall Bridget, Defining Southern Gothic. Critical Insights: Southern Gothic Literature, 2013), alongside featuring characters who may be involved in the African-American folk spirituality of hoodoo (aka low country voodoo).

Within Southern Gothic / Gothic Americana work there is often a strong sense of spirituality, which connects with a wider sense of deeply embedded religion within the South. This takes in the aforementioned hoodoo and also Christian religious beliefs, which can be considered divergent from mainstream religion in a number of ways, including the strength of conviction of its believers and the manner in which they express their beliefs. It is frequently characterised by a devout belief in literal deliverance and damnation – of heaven, hell and the rapture – and also through the rituals of a number of its adherents, which can include snake handling, speaking in tongues and full immersion baptisms in rivers.

(Above: author and educator Harry Crews.)

(Above: author and educator Harry Crews.)

Part of the lineage of Southern Gothic work is the Southern Gothic subgenre of American literature, which has had 20th century work by Harry Crews, William Faulkner and Cormac McCarthy associated with it. This often has a distinctive aesthetic and atmosphere where flawed, disturbing and eccentric characters live in warped rural communities of the American South. Such literature frequently has decayed or derelict settings, grotesque situations and sinister events which relate to or stem from the poverty, alienation, crime and violence featured in them, which can result in despair and madness.

These are themes which can also be found in some of Daniel Woodrell’s novels, such as Tomato Red (1998), which depicts a small town edge-of-rural Southern hardscrabble way of life, where many of the characters have a fatalistic acceptance that things are just how they are or will only end badly.

Southern Gothic related themes have also been explored in other more recent work, such as Walter Moseley’s series of novels about the unofficial / private detective Easy Rawlins (1990-), in particular the Easy Rawlins origin novel Gone Fishin’ (2002). In contrast to the majority of Easy Rawlins novels, which are often set in urban Los Angeles, Gone Fishin’ takes places in the American rural South, and features a witch-like character named Mama Jo, who practices a form of voodoo, and administers an effective form of medical aid based around folkloric remedies rather than traditional Western medicine.

Alongside such literary work, the genre of Southern Gothic music, which is also known as Gothic Americana or Dark Country, explores similar themes and often has interconnected dark lyrical subject matter. Musically it draws from traditional country, folk, blues and gospel, alongside contemporary rock but in terms of its themes and atmospheres it appears to also take its influences from Southern Gothic literature. A prime example of this would be 16 Horsepower, who were active between 1992 and 2005, having been founded by David Eugene Edwards and Pascal Humbert, who were joined for the bulk of the band’s existence by Jean-Yves Tola.

16 Horsepower’s work has a notable haunting quality, with their releases invoking religious imagery and dealing with conflict, redemption, punishment and guilt. Although their work draws in part from gospel and religion, it is not so much a form of straightforward religious revivalism but rather contains a sense of being haunted by sins, of telling the stories of cast out and lost souls left to wander the land and forests as they seek or are unable to find redemption.

(The background of 16 Horsepower is deeply intertwined with Southern religion, as co-founder David Eugene Edwards spent much of his youth accompanying his grandparent as he travelled from town to town in order to preach.)

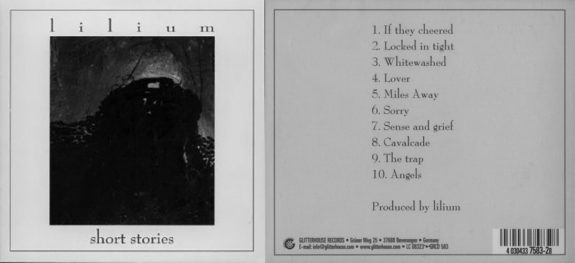

Working as Lillium, Humbert and Tola have also released three albums during and post 16 Horsepower, and their album Short Stories (2003) is well work seeking out. As with 16 Horsepower, it continues along a Gothic Americana path, and also conjures atmospheres of lost souls seeking redemption but, as with much of 16 Horsepower’s work, this is often depicted in an abstract sense, in contrast to some of Edward’s more directly religious orientated post 16 Horsepower solo work, and it creates an evocative, timeless sense of the landscapes and dusty plains of America.

The sense of an untamed, unknown and at times mystical South has been frequently used in film and television dramas and documentaries, often of a mainstream, critical and/or commercially successful nature. These include the steamy moral swampland of the vampire orientated True Blood (2008-2014); the folkloric/occult-like characteristics of crime in the first season of True Detective (2014); the unfettered sexuality, self hatred, guilt, back land swamp living and recidivist characters of Paperboy (2012); the urbanite tourists or military personnel incurring the wrath of Southern folk and being hunted down in the forests, swamps and rivers of Deliverance (1972) and Southern Comfort (1981); the independently produced and released but fairly high-profile theological action-horror Red State (2011), where in a small Southern Town an extremist religious community baits, entraps and disposes of what it considers decadent outsiders; the culture clash between urban sophisticates and Southern ways in Junebug (2015); and via a documentary road trip through the Southern landscape and its creative, personal and religious edgelands in Searching for the Wrong-Eyed Jesus (2003).

The rural American South is also the setting for the preternatural unexplained occurrences of Takashi Doscher’s independently produced film Still (2018), which is set in North Georgia’s Appalachian Mountains. As with some of the aforementioned culture, and other work which has been labelled Southern Gothic, Doscher’s film utilises and/or explores a sense of the American South as a potentially threatening, mystical or unknown “other”.

It tells of a young-ish married couple who live on an isolated rural farm, and initially it seems as though it will be a variation on Deliverance and Southern Comfort; two hitchhikers, who have a contemporary hipster-like youthful style that marks them as “not being from around these parts”, come across a young woman in the woods. When they ask for directions her behaviour seems a little off, hesitant and stilted but after a moment or two she appears to warm to them and offers them food. Played by Lydia Wilson, who also played the lead in the rural Britain set supernatural drama Requiem (2018), she has a visually very striking and distinctive appearance and this, accompanied by her manner, makes the viewer question if there is something of the preternatural siren about her.

As she walks with them towards her farmhouse, her partner tears across the field in his pickup truck, and seems extremely irritated and angered by their presence and also how they found the location of their farm. The hitchhikers are genuinely bewildered by his actions (“Is that a gun?” says one of them disbelievingly), in a manner which seems to be setting up film as a stereotypical depiction of city folk not understanding the ways of rural dwellers, and deadly conflict between the two groups. Despite his partner’s pleas not to, the young farmer drives the hitchhikers off at gunpoint, and presumedly their deaths.

However, the film is not a straightforward rerun of Deliverance / Southern Comfort tropes of deadly outsider rural Southern types, and this is intimated by the introductory sequence of old and modern half-toned newspaper covers, which show the couple looking the same age in the Prohibition era (i.e. 1920-1933, when the production and consumption of alcohol was prohibited in the USA). Although it has a preternatural premise, Still does not rely on genre shocks, action or special effects, but rather it is a meditative film which slowly draws the viewer into a beautifully portrayed, secluded and out of kilter rural world and couple’s life. Ultimately, as with Peter Strickland’s film The Duke of Burgundy (2014), in which as in Still a couple live a largely insular and out of kilter life, it doesn’t eschew but is also not purely or overly focused on the more genre or provocative aspects of its story, and becomes in large part an exploration of conflict, balance and acceptance in relationships.

The couple appear to be hiding some form of secret and, in particular the husband, do not want people on their land, nor for them to know how to get there. They live simply in an off the grid manner in a wooden farmhouse, which does not have electricity, running water, nor, apart from their pick up truck, any signs of modern conveniences, appliances, televisions, telephones, computers etc. How they dress also seems to hark back to earlier time, and as does the manner in which they live, it has a rustic simplicity to it, almost as though they are living in a self-contained time warp.

Another young hitchhiker, who was revealed in the newspaper covers of the introduction as having a rare form of terminal illness, is shown escaping from her hospital treatment, and then being lost in the woods. Due to her illness she collapses in the field next to the farm, and is subsequently shown waking in bed in the farmhouse. The husband again seems angered and wants her gone, but eventually he changes his mind, agreeing that she can stay – first until dawn, and then until the end of the week, with him expecting her to earn her keep by chopping wood. She does this until her hands are worn and bloodied, when he tells her she can stop, and during her other chores we are shown the seriousness of her condition as she weakens and coughs up blood, which she hides from the couple. However, the wounds on her hands are subsequently revealed to have healed miraculously quickly.

It becomes apparent that the husband and wife have gained some form of immortality, and have been living in this area without ageing since the Prohibition era. They have become immortal due to the unexplained properties of water they found in a local cave, which is depicted in a flashback sequence where they are shown in the Prohibition era to have hidden there after fleeing from the wife’s oppressive, controlling, and fundamental religious fanatic stepfather (who, in a manner that seems to conflict with his beliefs, is involved in the bootleg alcohol trade). Having evaded capture they settle on a nearby abandoned and secluded farm. However their life has become restricted in a number of ways; in order to remain immortal they must regularly drink the cave’s water, meaning that they cannot leave the farm, and also so as not to raise suspicion about their non-ageing, they must live a low profile and isolated life separate from wider society.

Prior to them discovering the immortality inferring and miraculous healing abilities of the local water, and after an initial period of being very fractious with one another, the couple are shown as having an affection and love for one another, and to be living harmoniously on their secluded farm. By contemporary times, and after having not aged for the best part of a century, this seems to have degenerated. The wife has essentially swapped one form of oppression and captivity under the thumb of her stepfather, for another; that of clinging on to immortality no matter what the cost, a need to hide their secret from the outside world and subsequently being tied to one another and this secluded farm, due to both this need for secrecy, and to be near the cave’s water, alongside her husband’s resulting controlling paranoia, and the dysfunction and conflict in their relationship this has all caused.

That this conflict plays out against a backdrop of stunning, and in some ways idyllic seeming, rural meadow, forest and mountain areas, serves to contrast and highlight the dysfunction present in the couple’s lives, while also adding a visually striking character to the film.

Although it is more conventionally scripted and visually presented, Still’s depiction of possibly preternatural unsettled events, atmospheres and dysfunction in a visually lush natural and forested setting, and the film’s lack of traditional genre visual shock or special effects, is not all that far removed from the setting and atmosphere of Josephine Decker’s film Butter on the Latch (2014). Decker’s film is set at a Balkan folk song and dance camp in the woods of California, and in A Year In The Country: Wandering Through Spectral Fields (2018) I wrote that it “is imbued deeply with a sense of dread and dysfunction [and could be called] a slasher in the woods without the slashing”.

I also wrote in Wandering Through Spectral Fields that Butter on the Latch could be considered “a form of folk horror where ‘folk’ could be taken as implying ‘being from the wild woods’; [in Butter on the Latch] these are woods that seem both tamed and untamed, connected to civilisation and yet those within it have also crumbled away from it” – comments which equally could be made of Still, and the couple’s divergence and transgression from the wider conventional world, life and norms.

The presence of the hitchhiker in their home upsets the fragile dysfunctional balance of their lives, and during the film the husband and wife are shown to be increasingly at odds, and during one heated argument the wife forcefully states that how they are living is not natural, and she wants out.

(The “unnatural” nature of their lives is poignantly shown when the wife shows the hitchhiker a set of unmarked graves, which she says are her stillborn children. Although it is not explicitly stated, there is a strong implication that this has happened due to some side effect of the cave’s water and their immortality.)

The husband resists strongly and violently against any suggestion that they leave and become mortal again, and seems to be possessed by an all-consuming paranoid insecurity about losing his immortality, or of any outsiders knowing of their secret and potentially taking away their eternal life, and will carry out any acts he considers necessary in order to protect it.

After she has stayed with them for a while the wife “cures” the hitchhiker of her fatal illness by giving her some of the water from the cave, and she reveals the secret of it and their lives to her. However, in order for the cure to be ongoing, the hitchhiker will need to stay in the area and keep drinking the water.

Eventually a form of cycle of life occurs in the film; after intensely resisting it, when his wife nearly dies after she temporarily leaves the farmhouse and access to the cave’s water, the husband finally realises that their way of life is no longer tenable, and that they cannot continue to attempt to live forever. He cedes to his wife’s wish for their immortality to end, and leaves the farm with just one bottle of the cave’s water, and his wife soon follows. The hitchhiker becomes the new immortal resident, and she is also immediately shown as being prepared to carry out fatal acts of violence in order to protect her immortality, when she guns down two outsiders who damage the farm’s unlicensed alcohol still. This still is a vitally important component of an immortal life on the farm, as it is a way that anybody living there can earn money in an under the radar manner, and thus live there without needing to overly connect or be noticeable to the outside world.

In a final emotionally resonant scene the husband is pictured sitting on the edge of a mountain, with his last bottle of the immortality giving water depleted. When his wife finds and joins him she holds his hand; they appear to have found their affection, love and understanding of one another again, and to have decided to let themselves age and die, and subsequently all the ageing that they would naturally have been subject to quickly descends on them.

The final shot is from behind them, as they sit together affectionately overlooking the natural beauty of the landscape, with the only indication of their soon coming mortality and ageing being the rapid silvering of their hair.

This scene is reminiscent of the final section of John Boorman’s film Zardoz (1974), where a couple, who have helped destroy and escaped from the stasis and imprisonment of a world based around a privileged classes’ immortality, are shown sitting side-by-side in a cave. Via time lapse photography they rapidly age, their children appear, grow to mortality and leave, after which the couple solemnly hold hands and collapse into old age and then death.

In Zardoz immortality has created a dramatically unequal society where those not in the elite (the “Brutals”) live in a wasteland, and are violently controlled by a warrior class in order to provide for the immortal elite (the “Eternals”), who live in “The Vortex”, which is protected by an invisible barrier. There the Eternals live in privileged liberal but conformist luxury, and due to their immortality they have become sterile, experience extremes of aimlessness, ennui and, in some cases, are inflicted with a catatonic form of living death.

Although more subtly expressed in Still, both it and Zardoz can be viewed in part as a consideration of the mentally corrosive effects of immortality, with both the Eternals in Zardoz, and the couple in Still, being shown to be living in a gilded, and ultimately dysfunctional and doomed, cage of immortality.

The double-edged sword nature, and practical problems, of humans attaining immortality is a theme which has been explored numerous times and in notably varied ways in cinema, comics and literature.

One of the recurring themes in much of such work is that when people do not age, as all around them do, this inevitably leads to them arousing suspicion. This is the case in 2015 romantic fantasy film Age of Adaline, in which a permanently 29-year-old woman, who has accidentally gained immortality through an unexplained magic realist-like event, has to spend her entire life on the run to avoid suspicion and the attention of the authorities, scientists and so on. This has resulted in every few years or so her needing to change her identity, style and leave her current home area, and knowing that she can never fall in love, as she cannot live a normal life with a partner.

The practical difficulties which immortality brings about in modern society are explored in Ross Welford’s 2018 young adult novel The 1,000 Year Old Boy, in which an immortal and unageing young boy finds modern-day life increasingly difficult. For many centuries he and his also immortal mother evaded attention and suspicion of their non-ageing, by living quietly and separately from others, and as in Still often living in a secluded rural way more in keeping with previous times, or by adopting a portable transient lifestyle. Today they can’t even rent somewhere to live easily, as people “want to know everything about you”, i.e. they require references, bank details and so on, which due to their off the grid and/or under the radar lifestyle, that they have adopted to avoid suspicion, they do not have. Also the increasing use of digital records, and a related ability to cross reference information, has meant that it has become increasingly more difficult to hide their secret immortality, as those who do become suspicious are able to investigate and discover details of their living and being the same age in previous years and centuries.

In 1972 horror film The Asphyx, and 1992 black comedy Death Becomes Her, immortality is shown to have physical problems or side effects. In both, those who have attained immortality are shown to carry on living no matter what physical injuries they suffer. This leads to a central character in The Asphyx eventually living life as a disfigured wanderer through city streets, while in Death Becomes Her a narcissistic holding onto eternal youth and physical beauty leads to two of the immortal characters becoming physical parodies of their former selves, whose rotting but eternally alive bodies are patched up with putty and paint in a manner nearer to house restoration or temporary car repair.

Science fiction film In Time (2011) also takes a technological, but near magic realist in its unexplained nature, approach to immortality; it depicts a dystopian near future where people stop ageing at 25, when a 1-year lifespan countdown on their forearm begins. Lifespan has become a form of commodity, and has replaced money as society’s currency, with the wealthy owning more lifespan and effectively being immortal, while the mass of the population literally live day-to-day, or even minute-to-minute, as they attempt to earn more lifespan at low paid menial jobs. The film becomes a critique of class divisions and inequality, dressed up in high concept science fiction trappings, and is left open-ended as a Robin Hood-esque character and his partner, who has rebelled against her status as one of society’s lifespan rich elite, attempt to crash the system by stealing ever larger sums of lifespan, which they intend to redistribute throughout society.

Vampire genre films have been somewhat fertile ground in which to explore the potential dangers of immortality. In German vampire film We Are the Night / Wir Sind Die Nacht (2010), a group of immortal and unageing female vampires live an affluent and decadent nightlife orientated lifestyle. However, for one of them the unending nature, aimless repetition and hedonism of their immortality has resulted in severe apathy and dissatisfaction, something which is heightened by her estrangement from her mortally ageing daughter. While the group of vampires in We Are the Night have managed to provide themselves with a luxurious lifestyle, in 1987 neo-western vampire film Near Dark a family like group of vampires, made up of males and females with differing arrested physical ages, live on the margins of society, in a way that is nearer to a previous century’s American frontier and outlaw ways of life, and the film’s depiction of their fringe existence has some similarities with the earlier mentioned characteristics of poverty, alienation, crime, violence and madness which feature in some Southern Gothic literature.

In contrast to both We Are the Night and Near Dark, in playful comedy horror vampire film Vamps (2012), two immortal female vampires, who have remained eternally young women, live fairly normal lives, and are constructive members of society with regular jobs. However, as in all the above, their immortality ultimately proves problematic, and they decide that, while they have had a lot of fun being immortal vampires, “being young is getting kind old”. One of them has fallen in love and become pregnant, but the baby will not survive unless she becomes human again. They choose to become mortal by killing the psychotic “stem” vampire who turned them into vampires, which will end their immortality and vampirism. However, as in Still, once their immortality ends their physical bodies are subject to all the ageing that would have happened without their immortality, and it is revealed that one of the women has acted selflessly, as she has been alive for many years, and she ages and disintegrates into ash – and as in the ageing sequence in Still, there is a pronounced sense of both melancholy, and also of finding peace in the relinquent acceptance of a return to the natural order.

Links:

- Takashi Doscher’s Still

- Still’s trailer

- 16 Horsepower

- Lillium

- Butter on the Latch’s trailer

- Josephine Decker’s website

- Lazarus Churchyard

- Warren Ellis’ site

- The Twilight Time release of Zardoz

- The trailer for the Arrow Video release of Zardoz

- Ross Welford’s The 1,000 Year Old Boy

Elsewhere at A Year In The Country:

- Zardoz, Phase IV and Beyond the Black Rainbow – Seeking the Future in Secret Rooms from the Past and Psychedelic Cinematic Corners

- Wandering from the arborea of Albion and fever dreams of the land…

- General Orders No. 9 and By Our Selves – Cinematic Pastoral Experimentalism

- Requiem – Further Glimpses of Albion in the Overgrowth and Related Considerations

- The A Year In The Country: Wandering Through Spectral Fields book

- Bare Bones and Fellow Travellers in Rif Mountain’s Phase III

- Katalin Varga, Berberian Sound Studio and The Duke of Burgundy – Arthouse Evolution and Crossing the Thresholds of the Hinterland Worlds of Peter Strickland

- Andrew Niccol’s Gattaca, In Time and Anon – Striving for the Stars in a Brutalist Retro Future and Other Near Future Tales

- Kill List, Puffball, In the Dark Half and Butter on the Latch – Folk Horror Descendants by Way of the Kitchen Sink

Arboreal Explorations 19

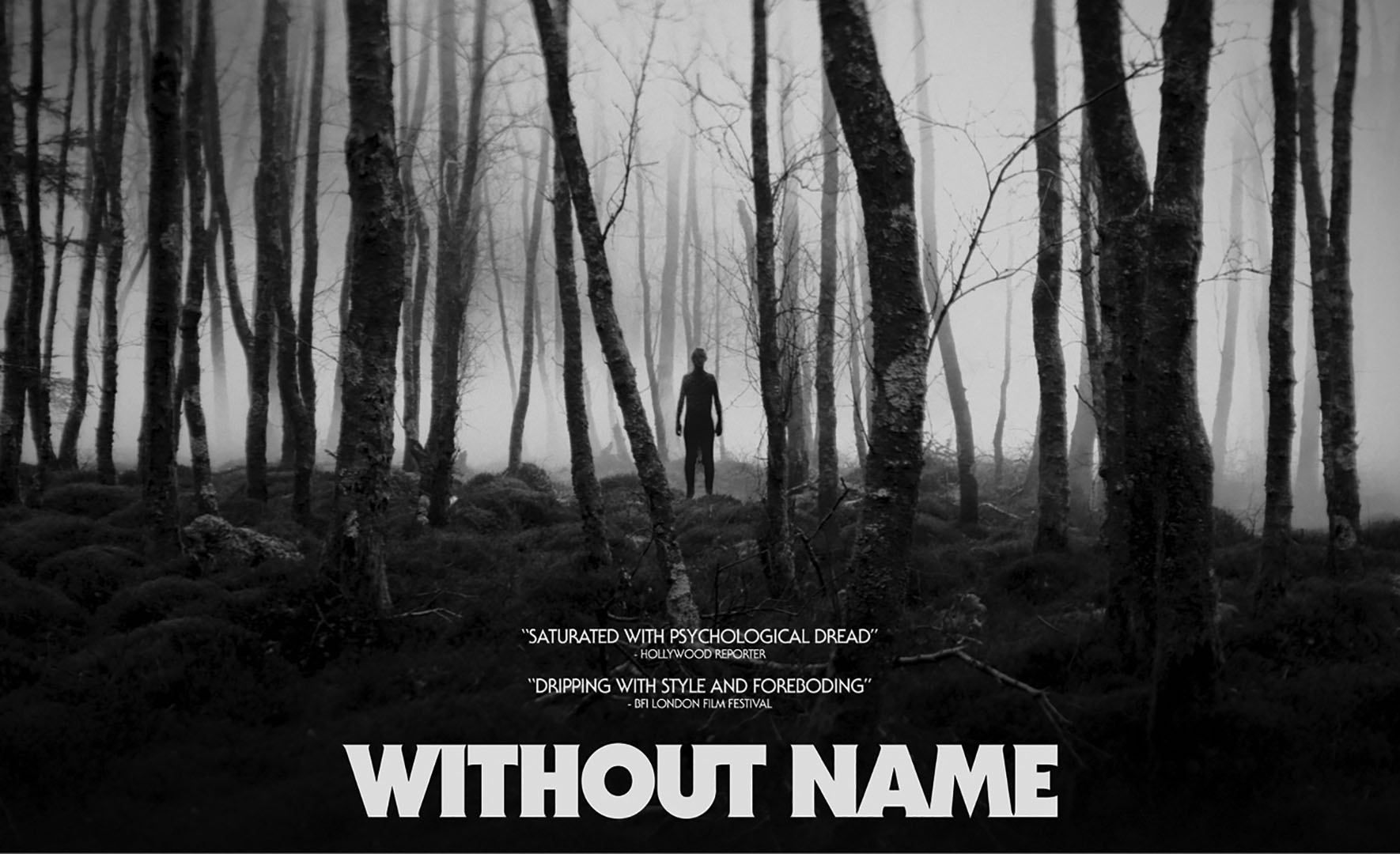

Without Name – Images from a Breached Threshold

I recently posted about Lorcan Finnegan’s 2016 film Without Name, which is a distinctive, unsettling woodland set often sunless and (literally) psychedelic folk horror-esque film.

When I was posting about it I noticed that there didn’t seem to be all that many different stills from the film online and I thought I’d remedy that in this post.

Also, when I was revisiting the film I thought that in part, which isn’t something I mentioned in the previous post, that it shares some similarities with Josephine Decker’s also unsettling woodland set folk horror-esque film Butter on the Latch, which I’ve previously described as being “a slasher in the woods without the slashing”, particularly in the way that they both use relatively still entrancing and quietly unsettling woodland and pastoral images…

The significance of man (vs nature) put into perspective…

Nature finds a way (if you look closely)…

Home not so sweet home…

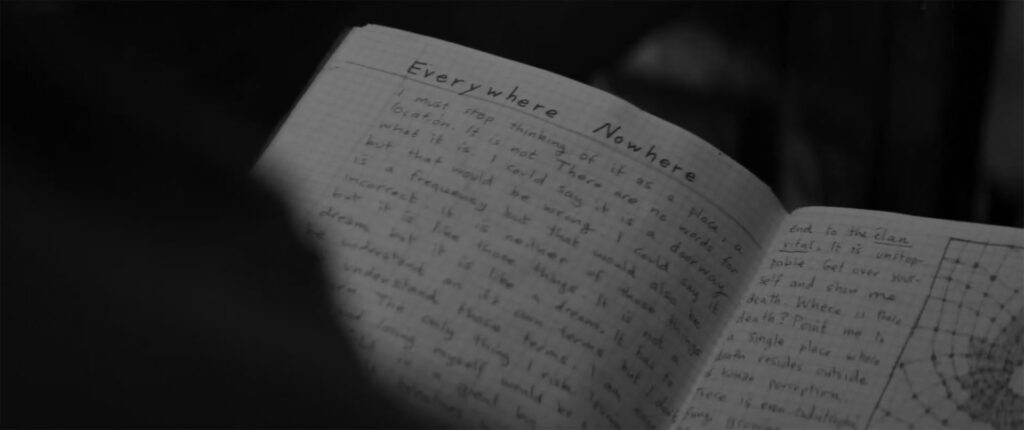

Notes on everywhere and nowhere from The Knowledge of Trees…

Watching and waiting…

Subtle intimations that something isn’t quite right…

Aura experiments…

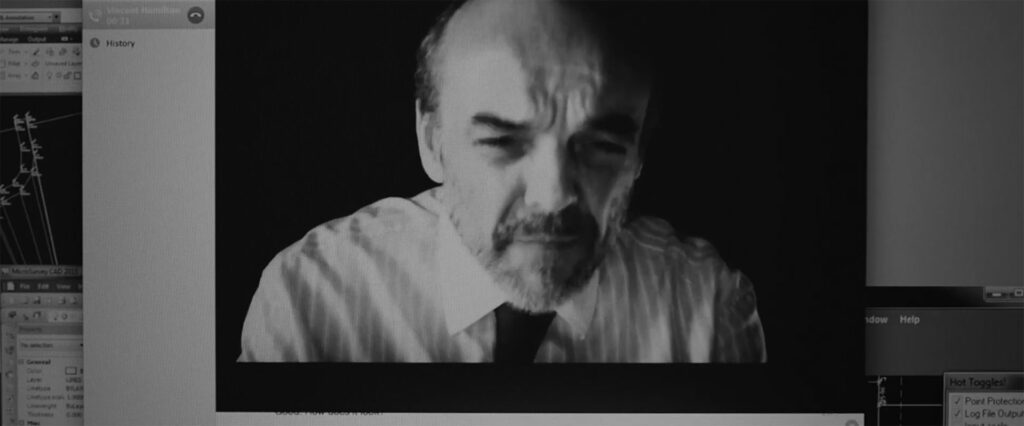

A remote planner of pillaging…

Waiting…

The boundaries are breached…

Searching for a man who will never be found…

Links at A Year In The Country:

Without Name – Stepping Over the Threshold of a Liminal Landscape

The Dark Pastoral Of Josephine Decker’s Butter on the Latch

Arboreal Explorations 18

Without Name – Stepping Over the Threshold of a Liminal Landscape

The 2016 film Without Name, directed by Lorcan Finnegan and written by Garret Shanley, centres around a middle-aged freelance land surveyor called Eric, who sets out on an assignment to survey an ancient isolated Irish forest for a developer that wants to level the area and build on it. The forest is said to have never been recorded on maps and only has a folkloric name, which means “without name” and appears to have some form of possibly paranormal or preternatural powers that it uses to defend itself and subsume the surveyor.

In some ways, the film utilises and follows some of the classic tropes of folk horror, in particular, those relating to an outsider being led a merry dance and to his (sort of) doom by and via a rural community, but in this case, the rural community is the land and nature itself.

While working on his survey, Eric stays at a cottage in the forest and discovers that the previous inhabitant, William Devoy, carried out extensive, apparently autodidactic, self-led esoteric research into the possibility that trees communicate with one another, the results of which he recorded in a notebook he labelled Knowledge of Trees which Eric finds in the cottage. This research included taking Kirlian photographs, some of which are still in the cottage, that he used to create otherworldly and uncanny images of plants’ auras, which in the film are said to change and indicate distress when they are damaged, and the use of natural psychoactive mushrooms etc which grow in the forest to connect with and understand what he thought of as the forest’s hidden language. The locals tell Eric that something about living in the forest eventually caused Devoy’s sanity to fracture, and after he was found catatonic and suffering from hypothermia in it, he was confined to a care home where he is shown to still be, now aged and still unresponsive.

Devoy’s research seems to suggest that the forest’s paranormal or preternatural powers may actually be the actions of a sentient forest and tree civilisation or consciousness of some form that exists beyond the understanding of conventional science. However, this is not straightforwardly nor directly explained and the film as a whole, without being overly wilfully abstruse, does not attempt to provide neatly resolved answers and explanations about all that takes place but rather to a degree remains intriguingly cryptic. Accompanying which rather than utilising graphic gore, extensive CGI, etc the film instead uses sound design, changes in lighting and subtly distorting visuals within the forest etc to create an unsettling atmosphere.

Alongside this, it lends itself to repeated viewings as it includes sometimes only briefly seen or heard “clues” which, on first viewing, may not be noticed or their possible meaning ascribed. These include Devoy having left a book in the cottage called Occult Defence, which suggests that he may have been attempting to protect himself against the powers of the forest and also when Eric drives through his city home on his way to the forest, there is a brief snatch of discussion on his car radio about liminal, i.e., threshold, places, which the forest is eventually shown to be and that in turn his position in it becomes.

Its story shares some similarities with M. Night Shyamalan’s 2018 film The Happening, in which the Earth and nature appear to be defending themselves and rejecting humankind by releasing an airborne toxin which causes humans to commit suicide. As with that film in Without Name, it is not so much humans per se that nature is rising up against but rather human civilisation and its destruction of nature alongside our widespread detachment from and disregard for the natural world. In Without Name, this detachment, disregard and destruction are given striking expression in a stark opening scene, which shows Eric surveying a quarry that, as the camera pulls away, is revealed as having been reduced to a moonscape-like industrial site which is denuded of nature. He is shown to be a tiny isolated figure who is dwarfed by the landscape, and this seems to suggest our potential insignificance or lack of power next to the scale and might of nature, the planet and existence as a whole, themes which the film goes on to explore, reflect on and develop.

This scene is followed by Eric then being shown living with his wife and son in a modern, notably starkly Brutalist architecture like block of urban flats where they seem to live an at least comfortably affluent life. Equally, there is evidence of considerable dysfunction and non-communication between them, which is given extra weight when it is later revealed that Eric is having an extramarital affair with the student who helps him to survey the forest, all of which in an oblique way seems to heighten a sense of Eric’s dysfunction and detachment from nature and how his actions may adversely affect it.

Throughout the film, the developer’s representative, who is only seen via video chats with Eric and therefore both him and his company keep themselves at a safe remove from any problematic local community responses etc, which may result from their actions, is shown as being dispassionately amorally unconcerned about the negative environmental affects that the development will cause. In turn, Eric repeatedly sidesteps his part in facilitating these by saying that he is just recording data and that neither he nor his student helper are responsible for what others do with it. The developer’s representative tells Eric that he chose him for the job as he is known for being discreet, and Eric, despite voicing some reservations, at his employer’s request, attempts to carry out the survey of the forest in a low-key under the radar manner in order to prevent any potential problems with regards to protests etc about the forest’s development’s environmental impact and he is deliberately vague or gives a cover story that he is working on an academic study of the forest to locals. All of this suggests that it is not the first time he has worked on contentious surveys and that he is not overly averse to using subterfuge in order to do so nor all that resistant to overcoming any qualms he may have about his work.

In an early scene, there is an indication that nature is not a meek agent that will continue to lie down and allow its destruction when, before setting off to the forest, Eric is stopped in his tracks by the sight of a single small plant which is determinedly and defiantly growing from a crack in the concrete floor of his block of flat’s indoor car park. This intimation of nature’s resistance continues, albeit in an unsettling paranormal or preternatural manner, when as soon as Eric begins his surveying of the forest, the lighting in it seems to ominously respond and change whenever he “invades” it by pushing the poles of his surveying equipment into the earth.

He also repeatedly glimpses a dark, featureless silhouetted figure in the forest, which remains constantly just out of reach. This figure may in fact be some form of paranormal guardian or assistant of the forest who helps it protect itself and warn off those that threaten it, although when there is an unexplained scattering and overturning of Eric’s equipment, he initially thinks that this and the shadowy figure may just be one of the locals “mucking about” or perhaps are the actions of somebody who does not want the land developed.

As the days pass, Eric begins to lose his grip on reality, which may in part be due to his use of natural psychedelics, which he and his helper are first introduced to by a free-spirited traveller that they meet who lives alone in a caravan in the forest, and that later Eric picks from the forest and prepares according to instructions in Devoy’s notebook. Eventually, it seems that, without being directly explained, rather than losing his sanity, this taking of psychedelics, and indeed that they grow in the forest, is part of a process which is part of a defence mechanism used by the forest through which Eric’s consciousness and place in reality and existence are accessed and altered. It becomes apparent that, in some way, he is being prepared or directed by the forest or some other related paranormal or preternatural power to become a replacement for its current guardian, the featureless figure which he has seen in the forest, who seems to be a preternatural bilocational parallel plane of existence projection or “otherly” body of Devoy who is shown as being still catatonic in a care home.

Eric’s existence also seems to be becoming bilocational when he is shown in the cottage watching himself in the forest. When his “otherly” body meets the shadowy guardian figure amongst the trees, the latter of these transforms into Devoy, who attacks Eric and defeats this version of his body, which appears to precipitate and enable Eric becoming a new replacement guardian and which, in turn seems to awaken Devoy’s “real world” body from its unresponsive state.

The final scene shows Eric alone in the forest, looking scared, confused and bewildered. As his transformation into the forest’s new guardian becomes complete, the final image is of him taking the same form that Devoy’s “otherly” body had before him as he becomes a featureless silhouetted creature amongst the trees of the forest. Has this happened or been instigated due to the forest having a form of sentience, and this is its punishment and warning to all who threaten it, or does it understand that Devoy’s real-world body is becoming old and will, therefore, eventually no longer be able to sustain and guide his “otherly” body in its role in the forest? Or is it due to Devoy himself wishing to escape from a role which his research led him to but in which he has found himself a trapped and unwilling conscriptee? This is left unexplained, as is whether the developer’s plans have been stopped in some way by what has happened to its contracted surveyor but there is a sense that the forest is an implacable, resolute and unending foe which now has, if not a willing accomplice, then at least a powerfully reinvigorated weapon in its armament.

Arboreal Explorations 17

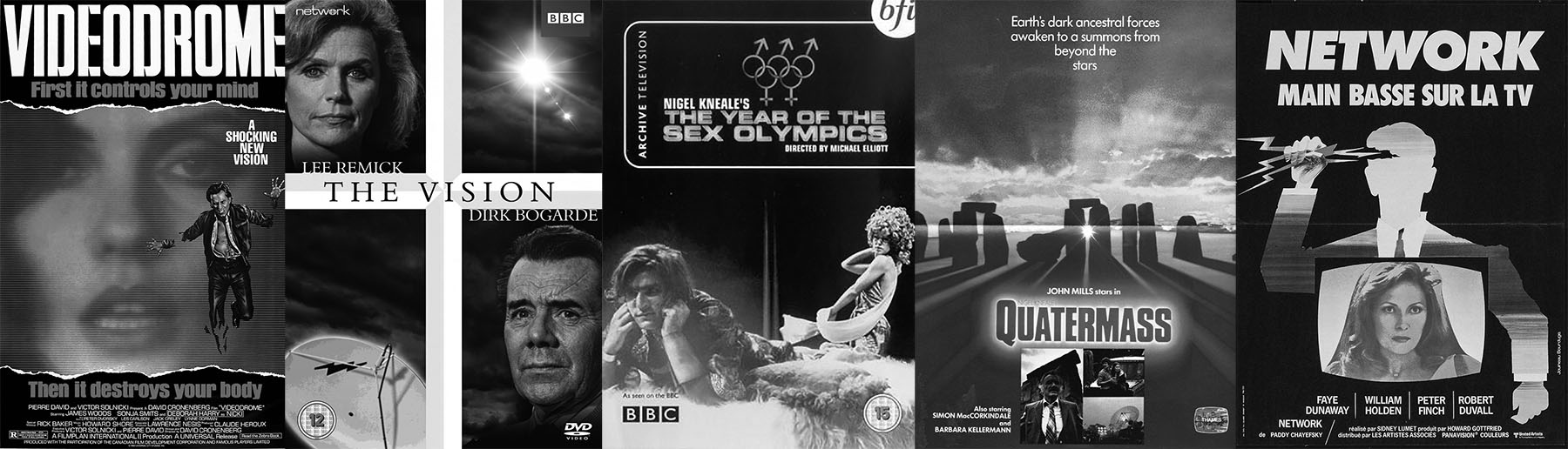

The Vision, Videodrome, Nigel Kneale and Network – Prescient Cautionary Tales of Corrupted Television and Media

As I’ve written previously at A Year In The Country, the subtly dystopic 1980 science fiction film Death Watch, based on the novel The Continuous Katherine Mortenhoe, could be considered part of a lineage, or possibly almost a mini-genre, of cinema, and even television, which looks critically, askance and judgingly at television, warning of its potential as a corrupt and/or corrupting medium. This post considers some of the other films and television dramas in that “almost mini-genre”.

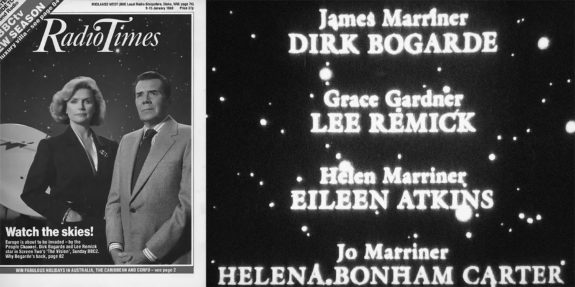

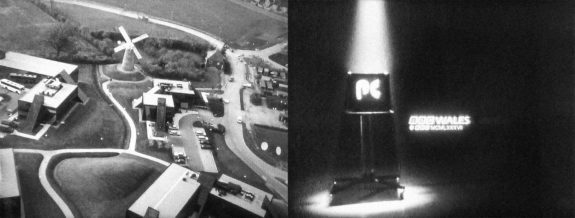

In David Cronenberg’s 1983 film Videodrome, set in North America, television literally corrupts and mutates viewers exposed to explicit, transgressive pirate broadcasts, turning them into mutated deadly killers, with the intention of “toughening up” an America gone soft, in order to fight an ill-defined and oblique, possibly liberal-minded, threat. This toughening up is also part of the insidious plans of an American right-wing religious television company in British BBC television drama The Vision (1987). In this the company begins broadcasting high-quality, no expense spared, audience friendly content in Europe and Britain, and it promises to be highly responsive to audience feedback, with it heavily promoting its interactive nature via an ongoing public phone-in service. However, it has an underlying agenda of influencing voting patterns through opinion piece programmes placed amongst the populist content, and behind the scenes manipulation, and even blackmail, of public figures in positions of power. It does this in order to prepare the populations of their target countries for what the company’s backers (a loose ideological and religious grouping known as “The Vision”) consider will be an end-of-days, armageddon-like conflict with the communist Soviet countries.

As with Death Watch, The Vision presents a near future day-to-day real world, with a subtle sheen to it, which in this case seems to set it apart from the more prosaic or day-to-day depictions of reality that can be found in some other television drama from a similar period. This may well be partly due to its apparently high-end production values, and also the inclusion of two former major cinema stars; British actor and one-time matinée idol Dirk Bogarde and Academy Award nominated American actress Lee Remick. Bogarde plays an aged former television presenter, who was previously a household name known for his warmly accessible demeanour, for whom work has dried up. Initially he overcomes his aversion to the company’s plans and accepts a job as its figurehead presenter, taking the path of least resistance and biggest cheque, in order to essentially be a trojan horse for their propaganda. Remick plays the director of the company, whose depiction of her character contains both a steely evangelical focus and more than a hint of cinematic star charisma and glamour.

Eventually Bogarde’s character rebels and he refuses to work for the company which, through their manipulation of the press, subsequently destroys his reputation and the lives of some he is closest to. His plans to reveal the company’s true purpose on its first night of broadcasting are skillfully handled and neutered by the company, and there is a sense that it is already too powerful, well-funded and efficiently organised to not succeed. While the series’ imagined Cold War based threat is now a period piece, the drama remains powerfully effective in its depiction of the potentially unaccountable and undemocratic nature of large media companies, and how the high cost of related infrastructure and effective large-scale promotion of media content, restricts access to just a few.

(Remick’s character compares this with how historically Europe’s information network was once controlled by just one organisation, the Catholic church, but that the low-cost and accessibility of printing broke this up, but that now the monopoly system was returning via the likes of her company.)

The drama ends on two somewhat unsettling, or even chilling, notes: the company’s television complex is seen from the air, with its stark angular modernity notably contrasting with a traditional windmill and greenery, implying that the company is already deeply embedded amongst the very heart of Britain; and in a metatextual manner as the credits roll, the camera zooms out to reveal that they are actually playing on a starkly lit television studio monitor, which leaves the viewer with an unsure sense of reality and also of the successful infiltration of “the vision” into television’s infrastructure.

While the drama focuses on large-scale infrastructure broadcast television, which was one of the dominant media forms and technologies of the time, it also appears to be somewhat analogous and prescient in relation to contemporary debates around social media which, as with the television channel in The Vision, offers a high degree of public interactivity, but is also owned and controlled by a small number of monopolies.

Elsewhere:

- The Vision – Network DVD

- Quatermass (1979) – Network’s Teaser Trailer

- Network trailer

- The Parallax View – Montage scene

- Opening Wednesday at a Theater or Drive-In Near You: The Shadow Cinema of the American ’70s

- Death Watch – Cinema re-release trailer

- Death Watch – Park Circus DVD and Blu-ray

- Death Watch – Shout! Factory DVD and Blu-ray

Elsewhere at A Year In The Country:

- Katherine Mortenhoe’s Journey Through a Subtly Dystopic Landcape

- The Dawning of a New Cinematic Age of Surveillance – Artifacts and Curios from The Conversation, The Parallax View, 3 Days of the Condor and The Anderson Tapes

- The Dawning of a New Cinematic Age of Surveillance – Three Days of the Condor

- The Stone Tape, Quatermass, The Road and The Twilight Language of Nigel Kneale – Unearthing Tales from Buried Ancient Pasts

- A Baker’s Dozen Of Professor Bernard Quatermass

- Quatermass finds and ephemera from back when

- Huff-ity puff-ity ringstone round; Quatermass and the finalities of lovely lightning

- Laurie Anderson’s O’Superman As Performed In A Real World Fever Dream

Arboreal Explorations 16

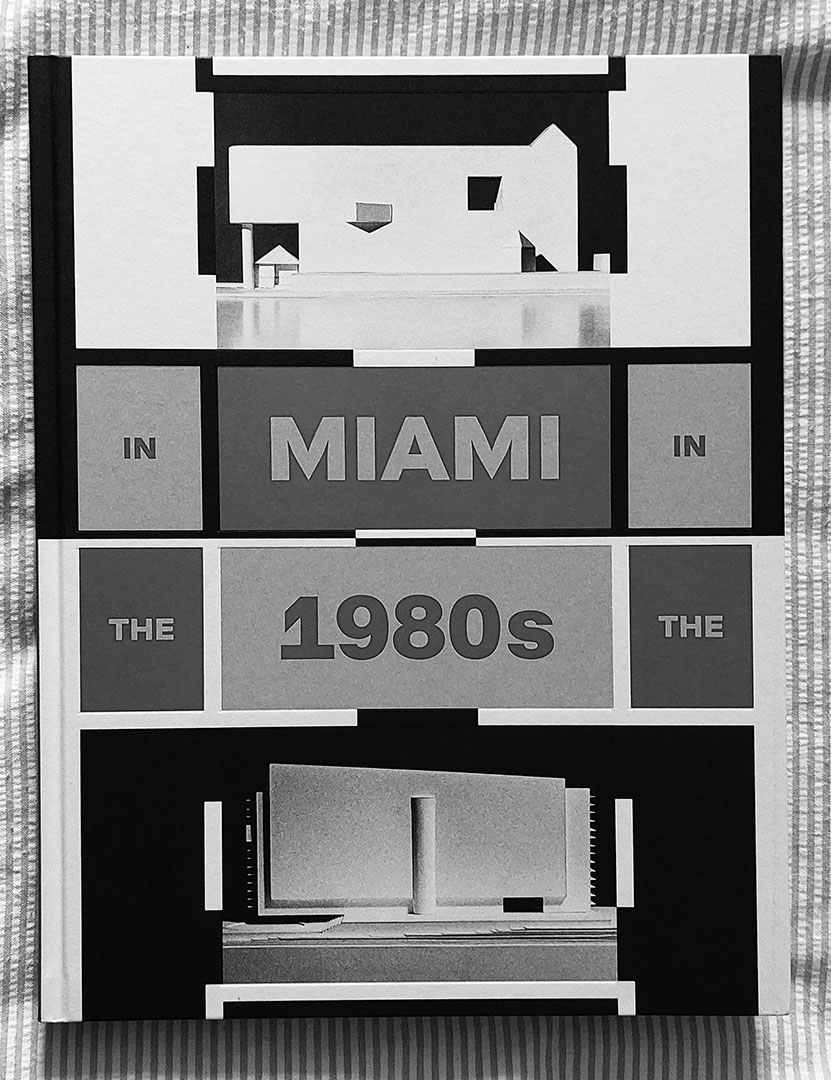

Returning to a Hyperreal Reality – Miami In The 80s and The Vanishing Architecture of a Paradise Lost

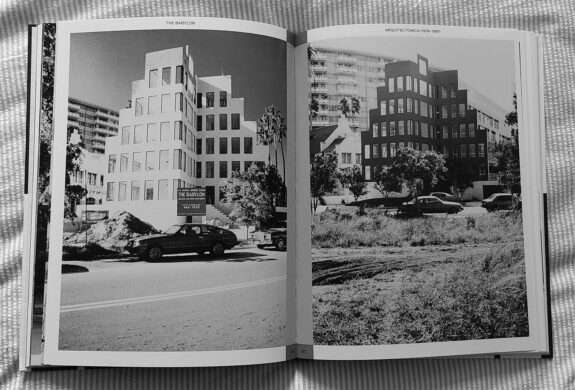

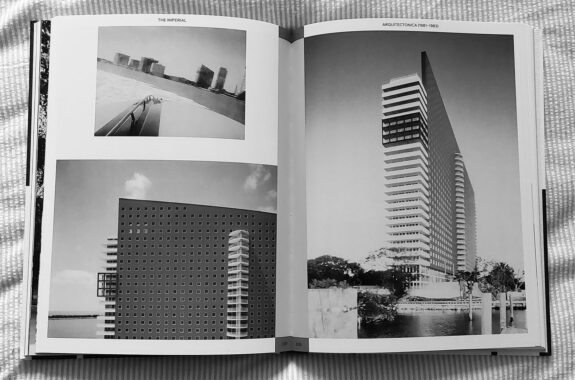

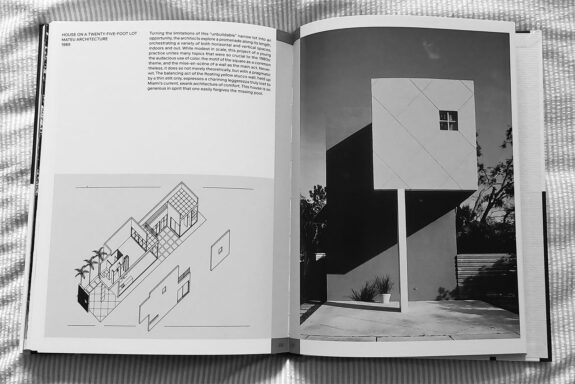

Often books which focus on modernist architecture feature buildings etc that, while sometimes grand in scale and intention, can also be somewhat utilitarian and even dour in terms of their design, which in turn is often due in part to their raw uncoloured concrete designs/facades.

Miami In The 80s: The Vanishing Architecture of a Paradise Lost, edited by Charlotte von Moos, takes something of a different tack through focusing on the modernist, colourful and at times playful and even more than a little surreal architecture of, as the book’s title suggests, the disappearing, demolished etc architecture of Miami in the 1980s.

Some of the buildings in the book seem to create a certain porousness between reality and fiction, where the glamorously gritty, at times almost hyperreal seeming colourful vision of life in Miami back when as depicted in the iconic 1980s buddy police drama series Miami Vice had bled through television sets and taken root in the real world…

Links at A Year In The Country:

Links elsewhere: