Gone to Earth was adapted from Mary Webb’s book originally published in 1917 and directed and written by Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, who also collaborated on a number of other films, has long been something of a favourite around these parts. As I’ve written before, its depiction of the story seems to be straining at the very seams of acceptable cinema mores of the time, and features some wonderful, almost surreally vivid Technicolor views of the British countryside.

Set in the late 19th century amongst the landscape around a small rural town on the border between England and Wales, the plot involves a free-spirited young woman named Hazel Woodus who lives a rural life close to nature that is closely connected with older magical and supernatural beliefs. She marries a kind-hearted parson but, in part due to her husband’s unspoken attempt to create a respectful union between them, which precludes all but the most chaste of physical intimacies until she is “ready to be his wife”, she comes to feel rejected by him. She is driven into the arms of a predatory and manipulative squire, who is somewhat mocking of the parson’s religious beliefs and also something of an almost archetypal cad and bounder, and runs away with him to his home. This leads to conflict and ultimately tragic and deadly confrontations between the protagonists and also the society they live amongst, with regards to belief systems, morals, passions and the nature of their love and fidelity for one another.

It takes its title from a fox hunting cry used to indicate when a fox has “gone to earth” in a burrow, and most of the film was shot on location around the town and parish of Much Wenlock in the English county of Shropshire, and made use of many local people as extras, choir members etc.

The film had a troubled release as, although he was apparently involved throughout the filming, the executive producer David O. Selznick disliked the finished version. Although the exact reasons for this are difficult to fully discover, it has been reported that he accused the filmmakers of sticking too closely to the novel and not making the film as originally planned. Accompanying this, it has been said that his dislike of the film was also because he considered it over concentrated on the beauty of the English countryside and did not showcase his wife Jennifer Jones, who played Hazel, to the degree and in the manner he wanted it to.

Also both Selznick and Powell and Pressburger tended to create their films in an auteur-like manner and were not used to outside interference in terms of their vision for their work, and therefore there may have been a resulting clash of wills. Alongside which, viewed now Powell and Pressburger’s various film collaborations can be seen as a precursor to more left of centre arthouse cinema, albeit generally produced and couched in a manner which placed it amongst mainstream cinema. In contrast to this Selznick came from a much more overtly mainstream cinematic background, and was best known for the high profile, award winning and hugely commercially successful epic historical romance film Gone with the Wind (1939), and so their may have been a clash of aesthetics between him and Powell and Pressburger.

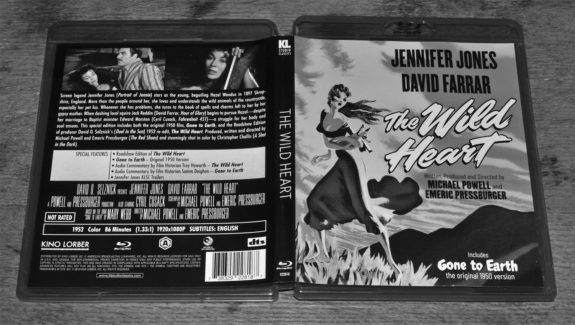

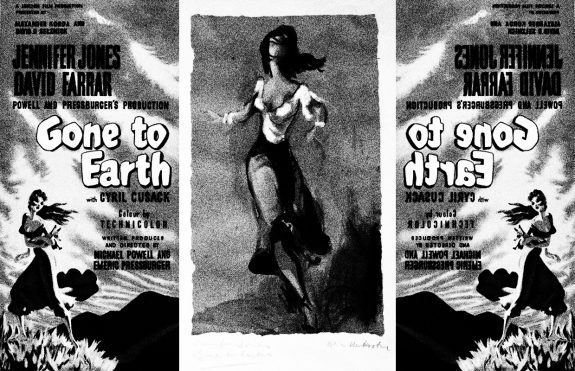

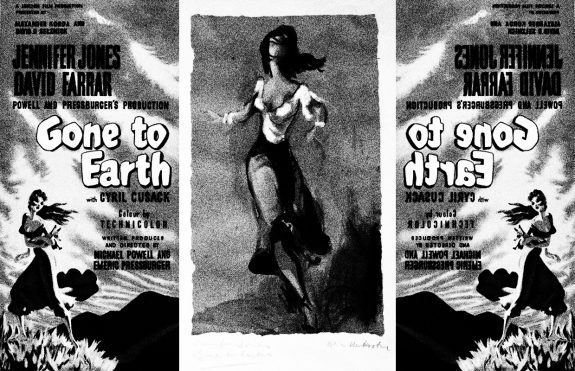

Selznick took The Archers, Powell and Pressburger’s production company, to court, in order to be allowed to change Gone to Earth and have the film’s European co-financier Alexander Korda fund reshoots. Although Selznick lost the case, he discovered that he had the right to alter it for the American release but would need to pay for any reshoots himself. He reassembled the principal actors, had some extra scenes shot in Hollywood and edited the film from 110 minutes down to 82 minutes, leaving around two-thirds of the original film intact. It was subsequently released during 1952 in the US as The Wild Heart.

I wrote about the film in A Year In The Country: Wandering Through Spectral Fields (2018) but at the time I had only been able to see the original Powell and Pressburger version, and to my knowledge The Wild Heart version was not still available for home viewing. It had been released on video cassette, more than once I think, in the US at some point in previous decades but copies of those (or even information about them) was difficult to find. All the various UK and elsewhere in the world home releases were always of Gone to Earth and for a long time I thought I would never get to see The Wild Heart version of the film. In fact I was not sure if it even still existed.

As I wrote in the last year of A Year In The Country, several years after first watching Gone to Earth I was browsing through the titles of upcoming films to be broadcast on archival television channel Talking Pictures TV, when all of a sudden I saw the title The Wild Heart. I thought “No, surely not”, but yes, it was indeed that The Wild Heart.

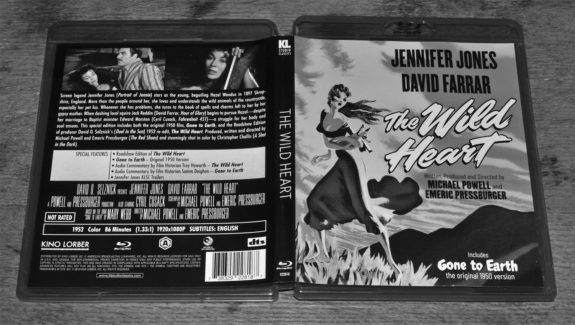

With seeing The Wild Heart there, I knew that it was available in the world, and discovered that in June 2019 it had been released on Blu-ray and DVD in the US by Kino Lorber, in single disc editions which contained both Gone to Earth and The Wild Heart. The Blu-ray and DVD are locked to Region A or 1, respectively, meaning that standard British Blu-ray and DVD players will not play them but because of, gawd bless ’em, multi-region Blu-ray players, I would finally be able to both watch and own it.

As referred to at the start of the post, Gone to Earth was filmed in Technicolor, which as I discuss in A Year In The Country: Wandering Through Spectral Fields (2018), gives it a distinctive non-realist character:

“[The film has a] Wizard of Oz-esque, Hollywood coating of beauty, glamour and quiet surreality which in part is created by the vibrant, rich colours of the Technicolor film process that it shares with that 1939 film… Often cinematic views of the British landscape are quite realist, possibly dour or even bleak in terms of atmosphere and their visual appearance and so Gone to Earth with its high end Hollywood razzle-dazzle which is contained in its imagery is a precious breath of fresh air… The film’s elements of older folkloric ways and its visual aspects combine to create a subtle magic realism in the film and the world and lives it shows, conjures and presents.”

In respect to this, there is a considerable difference in the colours and vibrancy of the transfers of the two versions on the Blu-ray. The Wild Heart’s transfer is much more vivid and seemingly also more in keeping with the original Technicolor production of the film, and this helps to create the abovementioned sense of magic realism. The transfer of Gone to Earth has a more muted quality, which seems to also slightly mute its depiction of a magic imbued landscape and story, and adds a more realist tone to it. The way this subtly changes the nature of the story serves to emphasise the way in which the visual nature of the film is inherently interconnected with and an important part of how it creates its almost otherworldly story.

Often in reviews etc of the two versions of the film The Wild Heart version is described as being inferior to Powell and Pressburger’s original Gone to Earth version but both have their merits. Gone to Earth has a more sedate, reflective pace that possibly grounds it more in previous decade’s cinema, and it also leaves more to the viewers imagination through not as directly explaining plot points etc. The Wild Heart’s story is more overtly signposted and made obvious, at times literally such as when a deadly open mineshaft has a warning sign that describes it as such. Accompanying this it has a certain rhythm and pace that draws the viewer in and makes the film feel more “modern” or nearer to contemporary film aesthetics, without having the sometimes almost frantic pace that some more recent film does.

Both versions of the film largely follow the same story arc, with the differences between the two and their running times being mostly due to a number of small incremental changes to how they are edited. One of the more major differences between the two versions of the film is that The Wild Heart includes an opening voiceover monologue that provides a background for Hazel’s story, and which has a Twilight Zone meets wyrd rural quality (and is also slightly dismissive of Hazel’s background and beliefs):

“The tale of pagan cruelty hangs in a mist of legend over the Earth’s far away places. This is one of them. The Shropshire border between Wales and England. Haunted like all borderlands. Here is a strange country of Roman ruins, crumbling heathen altars and a fearful ghost from whom the living still flee. It is the Black Huntsman, who rides the night wind with his phantom pack over God’s Little Mountain. And those of gypsy blood still whisper that to look upon the Huntsman, to hear his hunting horn and the angry baying of his hounds means… death. This is the story of Hazel Woodus, whose gypsy mother left her with a fear of the Black Huntsman’s godless cruelty. Fear born of ignorance. Ignorance that rejects salvation. It was the weak, the helpless and the untamed with whom this half gypsy girl found her only kinship. And this even as with the fox she loved, Hazel faced the Huntsman helpless and alone.”

Gone to Earth’s ending and its depiction of Hazel’s almost inevitable seeming, but still horribly shocking, doom seems harsher, bleaker and more sudden, and once it has happened the film ends very abruptly, which adds to its abrupt impact. This is slightly softened in The Wild Heart as the squire’s attempts to save her are slightly extended, and rather than ending suddenly on an image of what has caused her demise, this is followed by an image of a gnarled old leafless and subtly ominous seeming branch that was seen earlier in the film, a somewhat heartbreaking shot of Hazel’s shawl blowing in the wind atop the stone where she carried out a folkloric magical ritual in order to decide whether to run away to the squire’s and then an image of a subtly desolate seeming empty landscape.

One of the film’s main underlying themes is the clash between older beliefs rooted in nature, as represented by Hazel, and more “civilised” newer Christian beliefs, as represented by the parson and his parishioners. Hazel is torn between the two: she still places great store in her more magical beliefs and wants to bond with nature but also wishes to be part of, connect with and be accepted by the modern world. To a degree Hazel giving in to her physical passion for the squire can be seen to represent her being drawn to a less “civilised” pre-Christian way of being and a connection with nature but the squire seems to be a corrupted, darkened depiction of such things. His often untamed and unrepressed desires and behaviour are not an expression of a positive connection with nature, that Hazel herself has and is drawn to return to, but rather a form of self-centred aristocratic hedonism and self-serving pleasure seeking.

(Although in The Wild Heart, he is possibly depicted as less of a cad, as when the parson arrives at the squire’s home in order to take Hazel home and reclaim her as his wife, it is revealed that Hazel is pregnant with the squire’s child, and he wants to stand by her and asks the parson to divorce her so that they can be married. Hazel is not said to be pregnant in Gone to Earth and, although it is apparent that the squire has genuine feelings for her, he maintains a more brusquely dismissive attitude with regards to the true nature of them. Conversely, in Gone to Earth in this sequence, the parson is considerably harsher and more dismissive in his interactions with Hazel.)

For a while Hazel is able to intertwine her older magical nature based beliefs and ways of life with the modern world and more modern Christian beliefs, albeit with varying degrees of problems and even dysfunction. Despite marrying a parson and attempting to assimilate herself into the Christian faith and the modern world, often when Hazel has problems she turns to the book of spells and charms her gypsy mother left her; she also continues to keep a beloved pet fox, who she calls Foxy, which can be seen as a symbol of her connection with nature and a related belief in older magical ways. However it seems as though she will not be allowed to continue living with the old and new intertwined, and because of her protection of Foxy (and therefore, it is implied, her refusal to relinquish the old ways), both she and the fox are ultimately doomed: in the final scene Hazel attempts to defend Foxy from the dogs in a hunt that the squire is taking part in, and after scooping up Foxy she attempts to outrun them, which leads to tragic consequences.

Accompanying this there is a sense that Hazel’s personal transgressions and becoming untethered from her natural roots have an effect on and are similarly intertwined with the wider world. This unethering and its effects is unstatedly implied when she begins her affair with the squire at his home and leaves her pet fox behind at the parson’s rather than continuing her direct personal care and protection of it, and they are made overt when she is distraught by the squire’s servant killing blackbirds with a shotgun in order to stop them eating his fruit harvest, causing her to cry “It is as though I’ve killed them, coming here.”

Interconnecting with this response, Hazel is avowedly opposed to fox hunting and she is deeply concerned with protecting wildlife, and so her becoming involved with the squire, who is active in and relishes such hunting, further indicates how she has become untethered. This is heightened as one of Hazel’s main supernatural folklore inspired fears is that of the night wind riding “Black Huntsman”, as described in The Wild Heart’s opening monologue, and to a degree for her the squire is the human embodiment, or at least earthly representative, of this deadly wraith-like hunter.

(As an aside, some of the few overt expressions of the supernatural in the film involve the Black Huntsman, with the horses’ hooves of his disembodied pack sometimes mysteriously appearing on the soundtrack but remaining unseen to the viewer.)

It is not just through Hazel that the old ways and beliefs and more modern Christian beliefs are seen to intertwine and still exist: when the parson talks to God about how he will respect and protect Hazel if he marries her, he seems to be looking up at a large tree silhouetted against the night, as though his God still resides in nature, as did the old gods. Also when he gives a public prayer it is in front of a maypole, which are thought to have their origins in pagan Medieval cultures, and that in this scene has just been used as part of a folkloric ritual dance that takes place during a Christian church organised celebration. Although in the case of the maypole, any pre-Christian pagan meaning is likely to have been reduced to a mere shadow or echo as, while surviving Christianisation, by the time of the late 19th century when the film is set, it is likely they had lost their original meaning for those involved in the dance, as tended to happen in Britain as the centuries passed. With this in mind, rather than being a pagan totem, the presence of the maypole during the celebration can be seen as a more purely general celebratory symbol that acted to bring communities together.

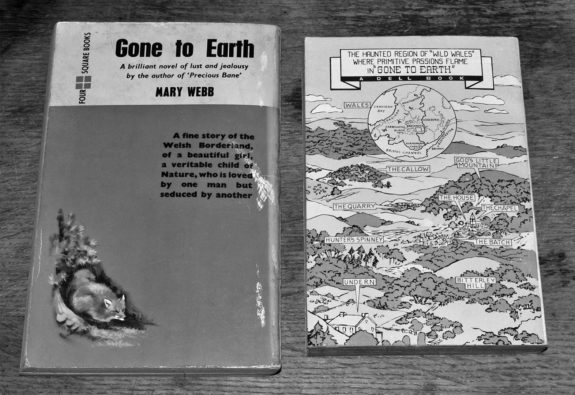

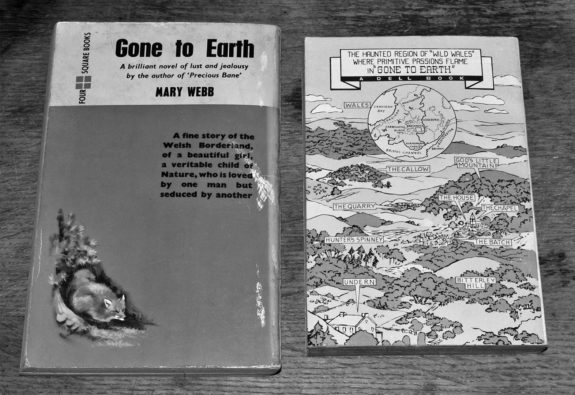

To my knowledge there were two different film tie-in editions of Mary Webb’s novel that, as discussed at the start of the post, Gone to Earth and The Wild Heart were adaptations of. These included a British and an American edition, published in 1959 and 1953 respectively which, as often tended to be the case during the time of their release, have illustrated rather than photographic cover designs.

In contrast with later film tie-ins, where that it is the book of the film tends to be emblazoned quite clearly on the cover, it is not immediately obvious that they are film tie-ins. The US edition has “Jennifer Jones stars in the motion picture” printed in small text on the cover, while the British edition does not mention any connection to the film on the cover, but on the first page inside there is some, also small text, that says “The cover is from the Powell-Pressburger film, distributed by British Lion.”

I assume due to legal obligations in regards to Mary Webb’s book, the US edition of the novel tie-in, which was published the year after the film had been released as The Wild Heart, still has the original title of Gone to Earth, which I expect may have confused some readers and buyers.

The US edition has a map of the story’s setting on the back, that is emblazoned with the text “The haunted region of ‘Wild Wales’ where primitive passions flame in ‘Gone to Earth'”, which connects with The Wild Heart’s opening monologue description of events taking place amongst haunted borderlands. This mention of a “haunted” landscape, some of the semi-magical rural folklore of the film, along with the Harps in Heaven song sequence, which is sung by Hazel atop a hill to the harp accompaniment of her father, and has an enchanting otherworldly quality not dissimilar to acid folk of the late 1960s and 1970s, seem to presage the current interest in all things “wyrd” or “otherly” folk and pastoral. Or, as I say in A Year in the Country: Wandering Through Spectral Fields:

“As a film it… appears to be a forebear of later culture which would travel amongst the layered, hidden histories of the land and folklore, showing a world where faiths old and new are part of and/or mingle amongst folkloric beliefs and practices… In some ways the air of not-quite-real-ness that can be found in Gone to Earth makes it seem like a forerunner to the more adult fairy tale side of the Czech New Wave (especially Valerie and her Week of Wonders from 1970 and possibly Malá Morská Víla/The Little Mermaid from 1976) and also of the style, character and imagery of a younger Kate Bush, of a free spirit cast out upon and amongst the moors.”

Connected to this sense of cultural forebearing, Samm Deighan, a writer and one of the editors of the horror film, literature and art magazine Diabolique, provides a commentary for Gone to Earth on its Blu-ray released by Kino Lorber, in which she talks of how the film can be seen as a precursor to what have come to be known as folk horror films (such as The Wicker Man released in 1973 etc). She suggests that Gone to Earth is not quite fantasy but edges on it, in part via, as in some folk horror film, the central character of Hazel having a near supernatural connection with the Earth and nature, one expression of which is her almost witch’s familiar-like pet fox who, as suggested previously, she seems incomplete and out of balance without.

Alongside which, and providing a line of connection between the two, The Wicker Man’s depiction of a pagan nature based belief system that openly embraces sexuality in conflict with a pious representative of Christian beliefs who denies his sexual desires can be seen to have been prefigured in Hazel’s struggles in Gone to Earth, and her, the parson and the squire’s conflicting beliefs and desires. And as in The Wicker Man, the characters and beliefs in Gone to Earth and The Wild Heart are depicted somewhat ambiguously; nobody, nor their beliefs, are depicted in a clear cut unambiguous manner. Rather there is more of a continuum of good and bad, right and wrong and so on. Considering this, one of Gone to Earth’s dominant underlying themes could be considered to be a depiction of the challenges and complexities of beliefs, both personal and systemic, and that none are “right” or “wrong”.

During her Blu-ray commentary for Gone to Earth, Deighan also discusses academic Tyson Pew’s comments on Powell and Pressburger’s somewhat odd and unsettling pastorally themed A Canterbury Tale (1944), with her saying that Gone to Earth can be seen as a form of sequel to it, and that Pew’s comments on it can also be applied to Gone To Earth. She discusses Pew describing the way in which A Canterbury Tale “exposes pastoralism’s inherent perversity”, quoting him as saying:

“The sexuality unleashed throughout its storyline projects England as both idyllic and menacing. The crux of A Canterbury Tale rises in its melancholic longing for a pastoral past that never existed and in this manner melancholia fractures national fantasies of historical and contemporary identity. In its vision of an edenic world of relaxed labour and bucolic virtue, the pastoral is as fantastic a genre as fairy tale or science fiction because this vision depends on the unobtainability of, indeed the impossibility of, this past in the present.”

This connects with the intertwining of a hauntological “yearning or nostalgia for a post-war utopian, progressive, modernist future that was never quite reached” with an otherly pastoral, wyrd folk etc related “yearning for lost Arcadian idylls”. Gone to Earth seems to be deeply threaded throughout with a related sense of yearning for the seemingly unobtainable, which finds its strongest expression in Hazel’s desire to find a way in which she can be allowed to connect with the modern world and her husband’s form of spirituality, while still being able to maintain and express her belief in the old, magical nature based ways and beliefs.

Elsewhere:

Elsewhere at A Year In The Country:

- Gone to Earth / The Wild Heart, the Haunted Region of Wild Wales and a Sidestep into Talking Pictures TV’s Broadcasts of the Overlooked, Shadowed Archives of Cinema and Television

- Harps in Heaven, curious exoticisms, pathways and flickerings back through the days and years…

- Gone To Earth – “What A Queen Of Fools You Be”, Something Of A Return Wandering And A Landscape Set Free

- Mary Webb’s Gone to Earth and Forebears of the Layers Beneath the Land

- Gone to Earth – Earlier Traces of an Otherly Albion

- Zardoz, Gone to Earth, The Owl Service, The Village of the Damned, The Prisoner, Quatermass, The Wicker Man, The Touchables, Sapphire and Steel, The Nightmare Man, Phase IV and The Tomorrow People – A Gathering of a Cathode Ray Library and Rounding the Circle