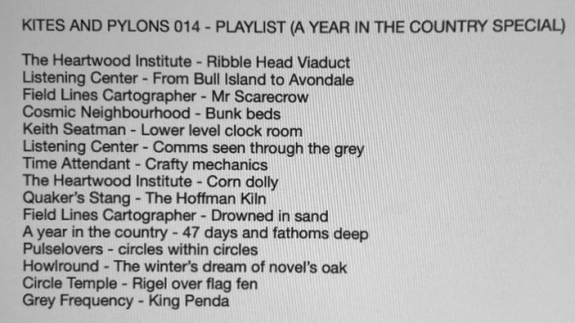

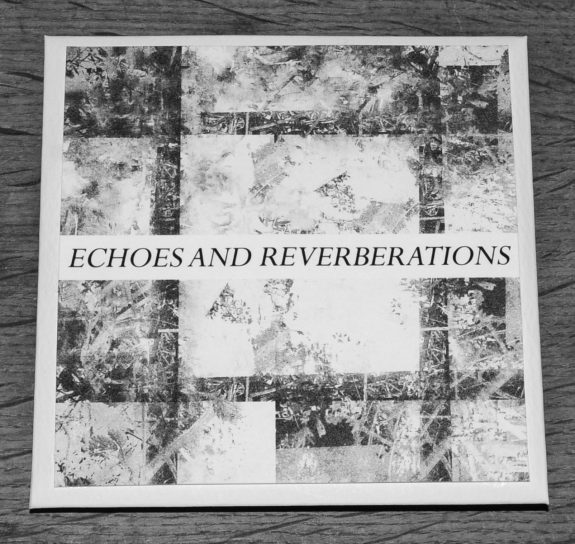

A selection of the reviews, broadcasts etc of the Echoes And Reverberations album:

“Amongst the hypnotic electronica from Grey Frequency, Listening Center and The Heartwood Institute are recreations of the atmospheres of Penda’s Fen, Survivors and No Blade of Grass, as well as pieces inspired by the scripts and soundtracks of imaginary films. The music is enhanced by field recordings from the length and breadth of our sceptred isles – from a suspension bridge in Herefordshire, a church in Worcestershire, a graveyard in Chiswick and a viaduct in the Lake District – and the end result is bewitching and enthralling, transporting you from wherever you’re hiding out the current hellscape to more comfortable, if apocalyptic, times and places.” Alan Boon, Starburst, issue 465. Visit the review online here and the print edition of the magazine here.

“…audio Polaroids of a secret cartography… a gentle lullaby for post-dystopian dreams.” Joe Banks, Shindig!, issue 95

“…every fresh listen adds another layer of understanding – or, perhaps, misunderstanding – to the experience, to conjure fresh and further phantoms around the dimly remembered moments of a decades-old TV show…” Dave Thompson, Spincycle at Goldmine

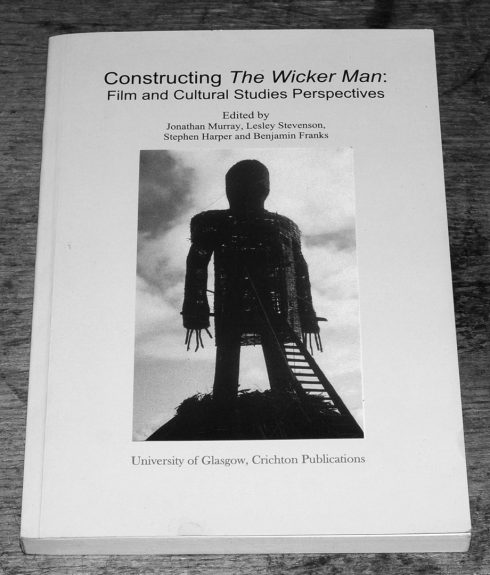

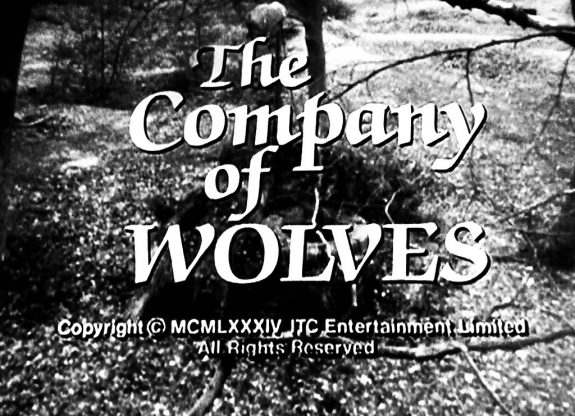

“The Radiophonic Workshop is the ghost at this particular feast… Dom Cooper’s What Has Been Uncovered Is Evil takes the Hammer film of Quatermass and the Pit as its focus, creating a soundscape of sinister electronics in a nod to Tristram Carey’s Martian soundtrack…” John Coulthart, feuilleton

“…rain drops, sun clocks and piano painted soundscapes bring listeners from the bucolic settings of its predecessors into a worldly odyssey of global kaleidoscopic changes” Eoghan Lyn, We Are Cult

“Sproatly Smith merge hazy dreamlike folk with eerie, ominous soundscaping in a piece inspired by the post-apocalyptic 70s TV series Survivors. The Ogham Stones by Depatterning imagines pagan carvings from County Wexford via brooding electronic experimentation incorporating surreal use of folk motifs. The collection holds together as a cohesive album with a shared aesthetic. Many of the pieces have an unsettling nature and sound believably like incidental music from vintage horror films.” Kim Harten, Bliss Aquamarine

“Pressed with a softly surging wide screen aspect, [Grey Frequency’s] King Penda deftly looms with impacting grace, much like some celestial watcher in the skies approaching, arriving and eventually departing our solar postcode, its pulsating kosmische toning emanating both a curiously radiance which at once serves as a mixed messenger herald of tranquil peace like welcoming or else a foreboding dark shadow of portent.” Mark Barton, The Sunday Experience

And then on to the radio etc broadcasts:

The Unquiet Meadow played something of a smorgasboard from the album across three episodes and included tracks by Sproatly Smith, The Heartwood Institute, Pulselovers and Grey Frequency. Visit the episodes here, here and here. Their Facebook page can be found here.

Steve Baker played The Heartwood Institute’s Ribble Head Viaduct on his On The Wire radio show, which has been something of a stalwart amongst the radio waves for several decades. Originally broadcast on BBC Radio Lancashire, the show is archived at Mixcloud and its blog is here.

Sunrise Ocean Bender played Pulselover’s and Grey Frequency’s tracks (alongside a track from sometimes fellow AYITC traveller Keith Seatman) on the Of Course As Well episode of their radio show. Originally broadcast on WRIR, the show is archived at Mixcloud and its blog post can be found here.

The Gated Canal Community Radio, hosted by Front & Follow and The Geography Trip, played Grey Frequency’s King Penda on their sohw (alongside a track by Polypores, another sometimes fellow AYITC traveller). Originally broadcast on Reform Radio, the show is archived at Mixcloud and the Gated Canal Community Radio website is here.

The Séance also played King Penda on their phantom seaside radio show (where you will also find some of Jodie Lowther’s intriguing work). Originally broadcast on Radio Reverb, totallyradio and Sine FM, the show is archived at Mixcloud and the episodes track listing can be found at their website here.

Mind De-Coder included Pulselovers The Edge Of The Cloud in amongst the otherly pastoral and psychedelic wanderings of its show, where you will also find the likes of Moon Wiring Club, Folklore Tapes, a track from the Ghost Box released Chanctonbury Rings, Meg Baird and some archival Tangerine Dream. The show is archived at Mixcloud and the accompanying blog post can be found here.

And then returning to some broadcasts of previous AYITC albums:

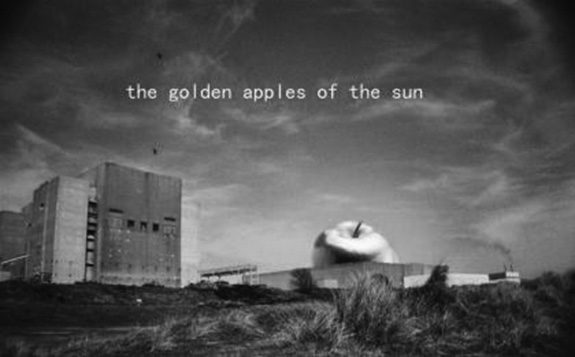

Golden Apples of the Sun included several AYITC released tracks amongst their journeys through “psych-tinged realms, pastoral folk, glitch, lo-fi electronica, hauntology and hypnagogic pop… a world beyond time, where the past and future intermingle in sun-dappled hallucinogenic soundscapes of strange and beautiful music”.

Included on the Tripping on Birdsong episode of the show were Sproatly Smith’s Watching You, Phonofiction’s Xylem Flow and Widow’s Weeds ft Kitchen Cynics The Brave Old Oak from The Watchers and also Depatterning’s The Keepers Dilemma from The Corn Mother, where they can be found alongside tracks by The Valerie Project, The Advisory Circle, Espers, Carl Sagan, The Twelve Hour Foundation and Jane Weaver. Originally broadcast on RTR FM, a resequenced version of the show is archived at Mixcloud and its accompanying blog post is here.

The Present Continuous, a project which explores the fringes and avant-garde of music and audio, included The Heartwood Institute’s Corn Dolly from The Corn Mother album, alongside the likes of Howlround and Belbury Poly in their Folk Horor and Hauntology Special. The show is archived at Mixcloud here and their site is here.

And finally, something of a repeat mention for:

Bob Fischer’s The Haunted Generation, which featured an interview with AYITC and a discussion about Echoes And Reverberations alongside “pastoral headspace, Cold War dread, Rob Young’s Electric Eden book, Noah’s Castle, Ghost Box, The Prisoner, his new book/album” and a fair bit more. Visit that at The Haunted Generation website here and the post about it at AYITC here.

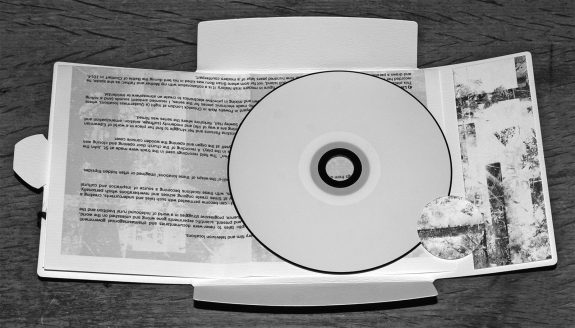

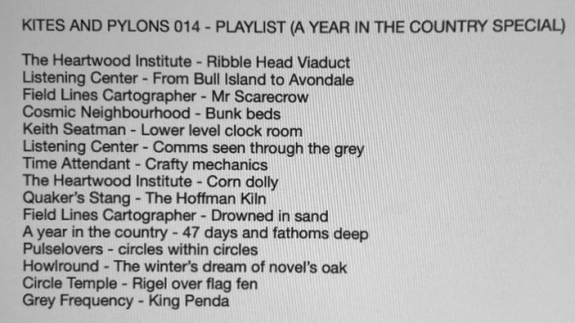

And an A Year In The Country Special of the Kites and Pylons radio show, which featured tracks from Echoes And Reverberations, The Quietened Village, The Quietened Bunker, The Corn Mother, The Quietened Mechanisms, The Watchers and All The Merry Year Round by The Heartwood Institute, Listening Center, Field Lines Cartographer, Cosmic Neighbourhood, Keith Seatman, Time Attendant, Quaker’s Stang, A Year In The Country, Pulselovers, Howlround, Circle/Temple and Grey Frequency. Originally broadcast on Mad Wasp Radio, the show is archived at Mixcloud here and the post about it at AYITC is here.

Thanks and a tip of the hat to all concerned. Much appreciated.

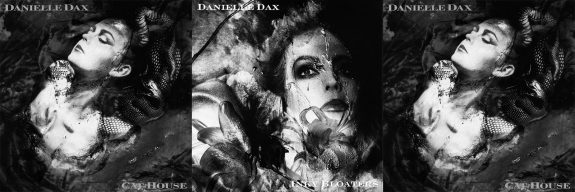

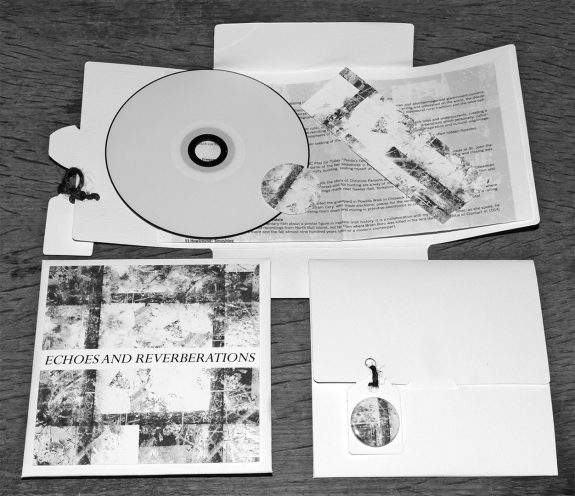

Echoes And Reverberations is a field recording based mapping of real and imaginary film and television locations. It is a reflection on the way in which areas – whether rural, urban, or edgeland – can become permeated with such tales and undercurrents, creating a landscape of the imagination where fact and fiction intertwine. Each track contains field recordings from one such journey and their seeking of the spectral will-o’-the-wisps of locations’ imagined or often hidden flipsides.

The album features music and accompanying text on the tracks by Grey Frequency, Pulselovers, Dom Cooper, Listening Center, Howlround, A Year In The Country, Sproatly Smith, Field Lines Cartographer, Depatterning and The Heartwood Institute.

Elsewhere at A Year In The Country: