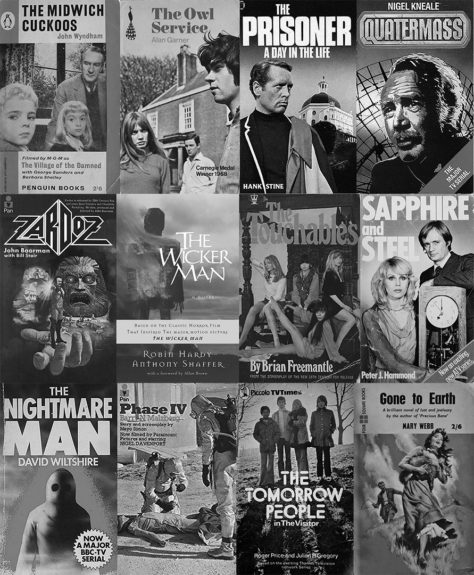

For the final post of the year I thought I would gather together some of the film and television novelisations and tie-in novels of some of the recurring reference points and inspirations for A Year In The Country, of which I have previously written:

“Often, when I was young, [novelisation and tie-in novels] were the only access I had to particular films and television shows, particularly in the days before home video releases of things became more ubiquitous, if the films etc were ‘too grown up’ for me to watch (!), I’d missed them at the cinema and so on. Viewed nowadays they can also have a particular period charm to them and can sometimes be almost like mini time capsules of particular eras.”

As I’ve also written about in an earlier post, I’m not sure that novelisations of films and television are quite as prevalent as they once were. Perhaps now that people have easier access to the actual films and television series there isn’t such a demand for them.

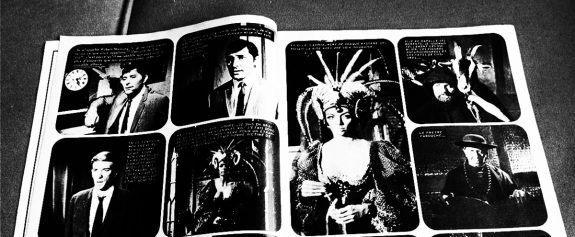

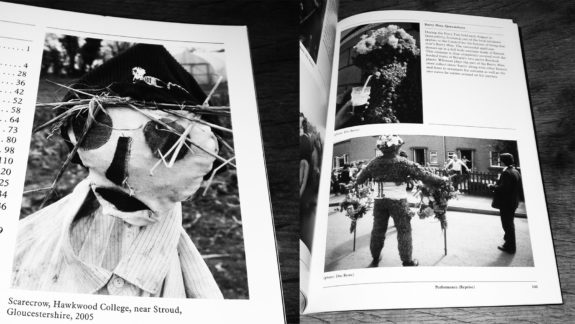

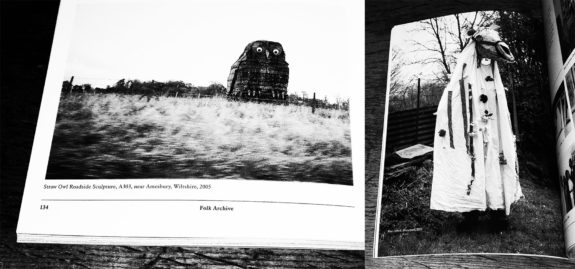

Also possibly with more niche films the number of potential readers and related budget would be too small to make it practical. It’s a shame really. Possibly for similar reasons fotonovels / fumetti adapatations which use stills from their source films don’t seem to be around much any more either , which is also a shame as I’ve always had quite a soft spot for them and they’re a good way of seeing and collecting together images from a film.

Above is the French fumetti adaptation of The Curse of the Crimson Altar featuring Barbara Steele in her horned priestess outfit, which in terms of style is probably the definitive otherly pastoral image of a “baddie”.

The post has “cathode ray” in the title as I think the majority of the related films and series I first saw on television and also, as with say some vintage hardware synthesizers, there’s a certain nostalgic romance and hauntological-like character to cathode ray television images and associated interference, glitches, scan lines and so on.

Collecting the books together also lets me revisit some of those recurring reference points and return to some longstanding cultural “friends”, while also rounding the circle of the year.

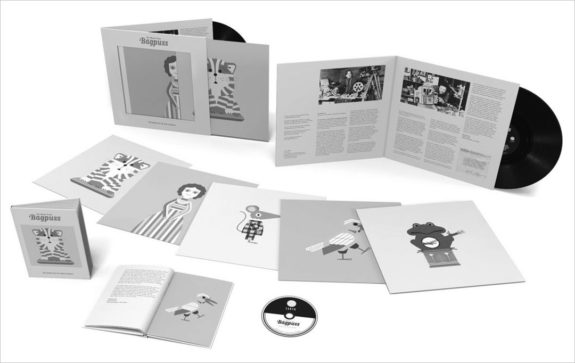

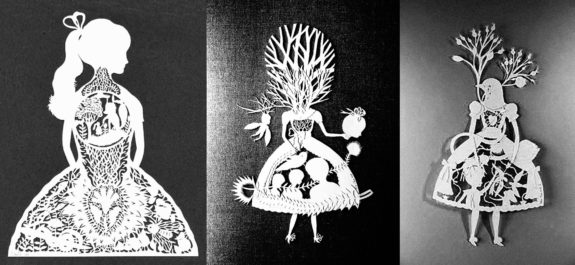

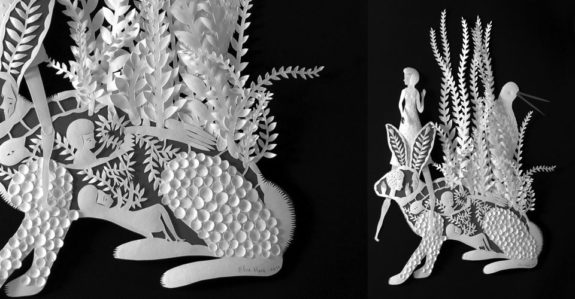

As a side note, Fantom Publishing have been reissuing some of the novelisations of ’70s children’s television dramas which have become hauntological and otherly pastoral reference points, including the rural time rift tale Children of the Stones, Arthurian eco fantasy tale Raven and the also Arthurian mystical The Moon Stallion, along with releasing a new novelisation of “the boy who fell to Earth” eco science fiction series Sky. The editions are handsomely presented in a distinctive in-house style that feature silhouette based illustrations inspired by the stories.

Above is The Midwich Cuckoos “Filmed by M.G.M. as The Village of the Damned” tie-in edition book cover. This may well be the definitive novel and film of things going science fictionally awry in the bucolic setting of a British village. The “Midwich Cuckoo” on the left of the book’s cover looks curiously both angelic and threateningly terrifying.

The Owl Service’s tie-in edition book cover does not really reveal or all that much hint at the mystical rural nature of the series, although the press quote on the back cover remedies that somewhat:

“Youth and love and fear in a modern summer, a Welsh valley where an age-old legend still has to live itself out again, generation after generation.”

Time to go and revisit the rather fine opening sequence for the series, which I think is probably one of the definitive otherly pastoral-esque of such things.

And then there is the cover for Nigel Kneale’s novel of the final series of Quatermass which is something of a classic design in all its posterised glory. I suspect finding a copy of this in the bargain book stand of a local newsagent many years ago and the story’s themes of dystopia, mysterious alien contact and stone circles as gathering and possibly reaping places is one of the main wellsprings that eventually led to A Year In The Country.

“Huffity puffity ringstone round…”

Above is John Boorman and Bill Stair’s novel of Zardoz. Problems with immortality, invisible barriers, entropic advanced technological and medieval lifestyles, The Wizard of Oz, a giant flying head…

As I’ve said before, Zardoz is such an odd and peculiar “Quite how did they get away with making that?” film.

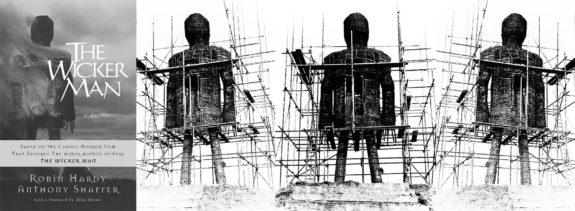

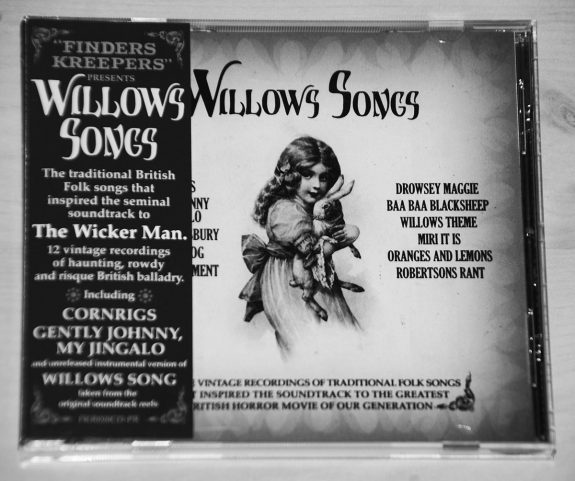

And then there’s the novel of the cultural behemoth and folk horror wellspring The Wicker Man. The original novel was published five years after the film was released and the cover in this post is one of the various reissues, which featured a foreword by Allan Brown who wrote Inside The Wicker Man.

The above right images are beind the scenes photographs of the construction of The Wicker Man structure but they could just as easily be images of an attempt to entrap this “creature”.

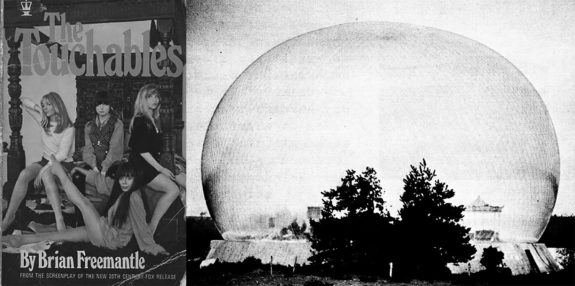

Above is the cover of Brian Freemantle’s rare and often hard to find novelisation of The Touchables film released in 1968. The film is something of a unique late ’60s psychedelic romp; where else will you find a story set in a huge see-through rurally based and real world life-sized inflatable bubble, complete with fairground attractions and a missing pop star?

And of course, creator of the series Peter J. Hammond’s Sapphire and Steel novel tie-in: “This is the trap. This is nowhere, and it’s forever.” Brrr.

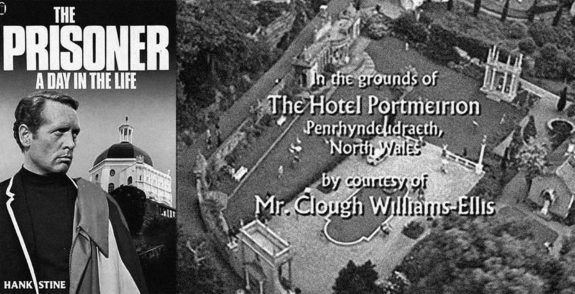

Above is one of the novel tie-ins of The Prisoner. If you have ever visited the real world village resort of Portmeirion where much of the series was filmed you may well think of the series as a dream set within a dream…

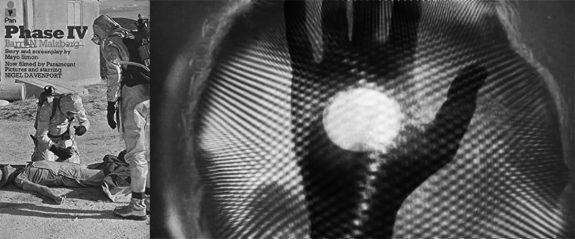

And then there is Phase IV. The legendary and long thought lost original psychedelic ending finally had a home release as an extra included with the reissue of the film in 2020, the announcement of which was good to hear. Next step a release of the film with the original ending restored and in pace.

Above is the cover for one of the The Tomorrow People tie-in novels, the opening sequence for which I have previously written that it seems like a mixture of “The Owl Service [opening sequence], The Modern Poets book covers from back when, Mr Julian House’s work tumbling backwards and forwards through time and the audiologica of The Radiophonic Workshop… but all filtered somehow through an almost Woolworths-esque take on such things… Despite that Woolworths-esque filter and the inclusion of a somewhat incongruous sliced pepper in amongst the other more overtly unsettling imagery, I still find it unsettling now.”

In terms of hauntological and/or otherly pastoral reference points it can be filed alongside the likes of the introduction sequences for The Owl Service, Children of the Stones, Noah’s Castle and The Omega Factor.

Then finally there is the 1959 edition of Mary Webb’s Gone to Earth, which features cover art taken from promotional artwork for Powell and Pressburger’s film adaptation released in 1950. Below is text on the book quoted from A Year In The Country: Wandering Through Spectral Fields:

“As a film [Gone to Earth] appears to be a forebear of later culture which would travel amongst the layered, hidden histories of the land and folklore, showing a world where faiths old and new are part of and/or mingle amongst folkloric beliefs and practices. Accompanying which, in the world of Gone to Earth (and it is most definitely its own world) the British landscape is not presented in a realist manner… Rather it has a Wizard of Oz-esque, Hollywood coating of beauty, glamour and quiet surreality which in part is created by the vibrant, rich colours of the Technicolor film process that it shares with that 1939 film… Often cinematic views of the British landscape are quite realist, possibly dour or even bleak in terms of atmosphere and their visual appearance and so Gone to Earth with its high-end Hollywood razzle-dazzle which is contained in its imagery is a precious breath of fresh air… The film’s elements of older folkloric ways and its visual aspects combine to create a subtle magic realism in the film and the world and lives it shows, conjures and presents [and it] creates a bucolic dream of the countryside…”