Whistle Down the Wind is one of those films that when I was young I remember as always being on TV, along with the likes of the 1970 version of The Railway Children, the 1968 adaptation of Oliver!, Chitty Chitty Bang Bang and The Wizard of Oz. I don’t know if they actually were repeated often, or if just I remember it that way.

It had been a fair few years since I’d seen Whistle Down the Wind but I recently found myself drawn to it; possibly because I’ve wondered about examples of expressions of the flipsides and undercurrents of the rural / pastoral in film and television that I saw when I was younger, and which subconsciously may have influenced A Year In The Country.

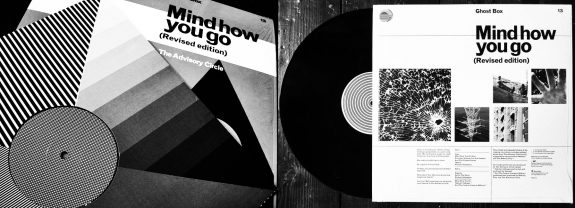

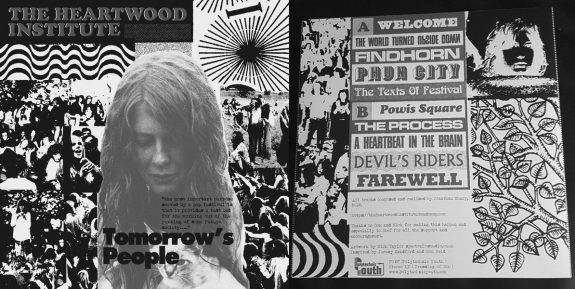

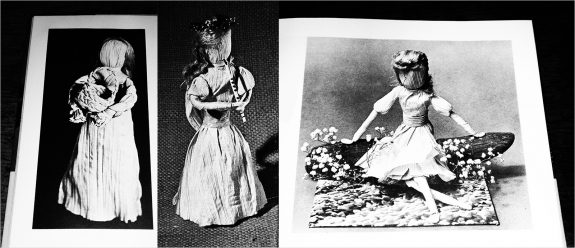

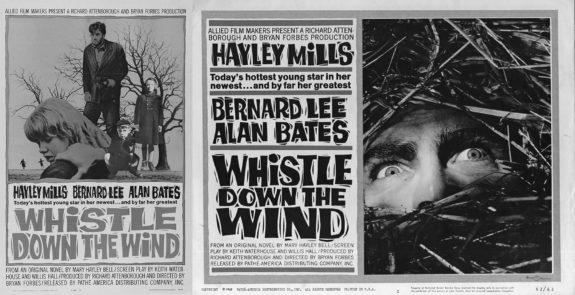

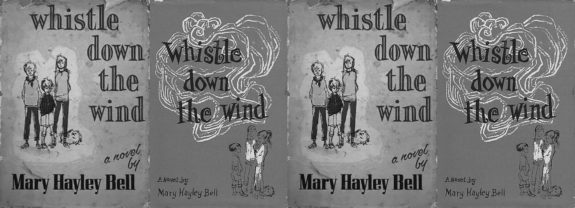

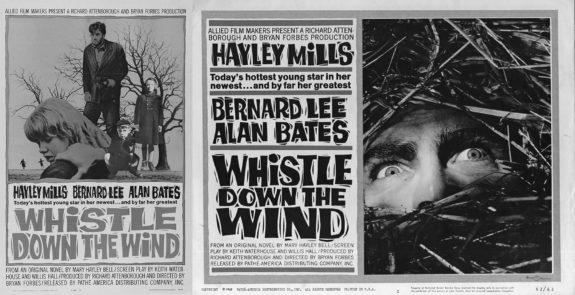

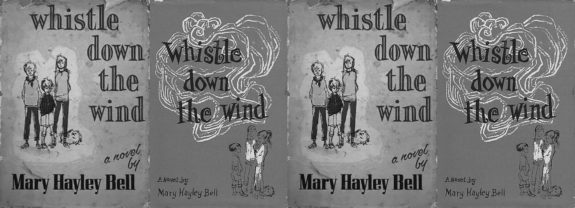

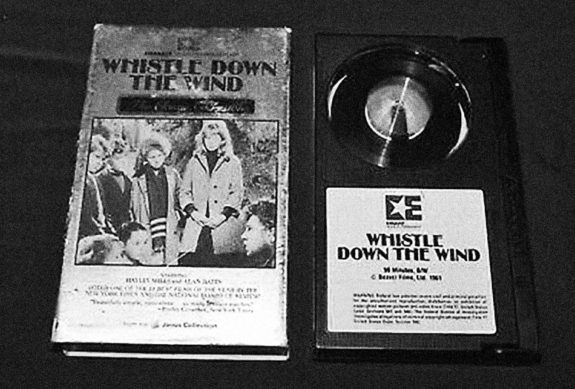

And then I came across the above left poster, which intrigued me somewhat and solidified my intention to rewatch it. The poster is one of those pieces of culture that seem hauntological-esque long before the idea/concept was formulated. With its bluntly cutout collaging, use of grayscale and duotone images and creation of a spooky atmosphere in a bleakly minimal pastoral landscape, it could well be the cover art for a contemporary hauntological / otherly pastoral orientated album. It’s just odd and curious. Why are two of the children apparently floating in mid-air? Why is the hand which is grabbing a shoulder disembodied? And if you look closely you will notice that Alan Bates is menacingly brandishing a broken bottle. Brrr (!)

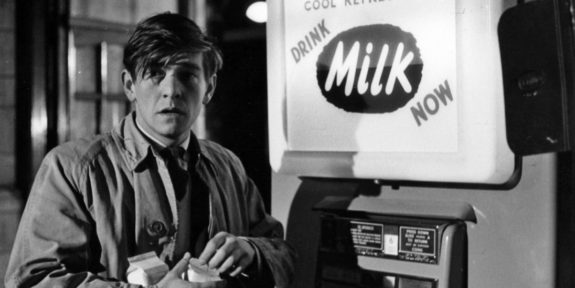

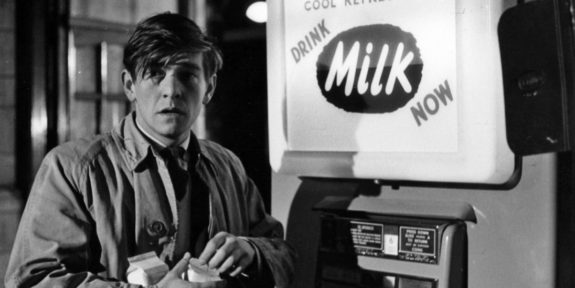

Whistle Down the Wind is set in and around a British Northern farm and rural town, and involves two sisters and a brother who are being raised by their father and an Aunty, as their mother has died. The oldest sister discovers an injured stranger in one of the family farm’s barns, and when she initially sees him he exclaims “Jesus Christ!” due to being discovered, before fainting. This, his beard and her religious education at Sunday School cause her to mistake him for the second coming of Jesus Christ, and she subsequently convinces her siblings and other local children that he is Jesus. The children do not tell any adults about him, as they are concerned he will be persecuted by them, as Jesus was in Biblical stories, and they bring him food and gifts. The man, whose name is Arthur Blakey, is actually on the run and wanted for murder, and he does not attempt to correct the children’s mistake, as he wishes to continue to receive their help and protection. Eventually the majority of the local children find out about the man and want to visit “Christ”, and there is an inevitability that his presence will somehow be revealed to the local adults, who are very aware of the manhunt which is taking place in order to track him down.

Released in 1961, it was adapted from Mary Hayley Bell’s novel of the same name, and starred her daughter Hayley Mills in a lead role as the older sister Kathy. The film was the first to be directed by Bryan Forbes, who over five decades worked as a director, screenwriter, film producer, actor and novelist. Some of his other credits include acting in the 1957 film version of Nigel Kneale’s Quatermass 2, producing and contributing writing to the parallel personal universe / preternaturally cloned life thriller The Man Who Haunted Himself (1970), directing The Stepford Wives (1975), in which a sinister organisation arrange for the replacement of a community’s wives with model housewife automatons, and directing and screenwriting British New Wave classic The L-Shaped Room (1962). Whistle Down the Wind’s screenplay was by Willis Hall and Keith Waterhouse, the latter of whom also wrote the screenplay’s for two other classic British New Wave films; A Kind of Loving (1962) and Billy Liar (1963). The murderer on the run is played by Alan Bates, who appeared in two iconic British New Wave films The Entertainer (1960) and A Kind of Loving (1962).

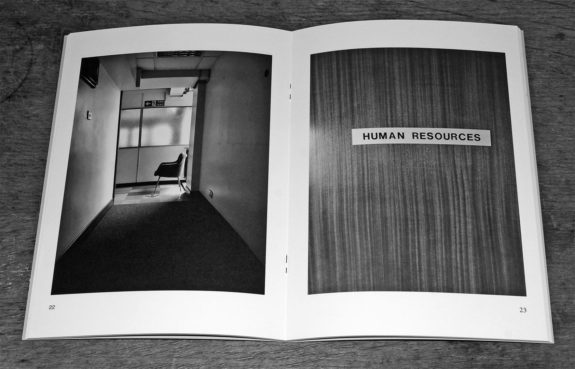

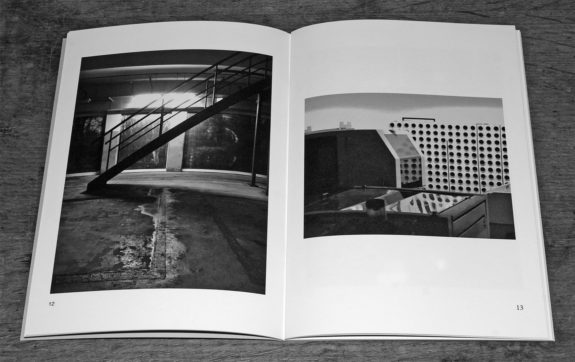

That some of those involved in Whistle Down the Wind’s making were also involved in British New Wave films is not surprising on watching it, as it shares a number of characteristics and criteria with them, including a Midlands/Northern setting, a realist aesthetic, a first time director and is shot in black and white. However, it does not tend to be included in the accepted canon of British New Wave films, possibly in part because it is more family viewing orientated, which is an area of cinema that is often excluded from more reverent critical opinion and acceptance.

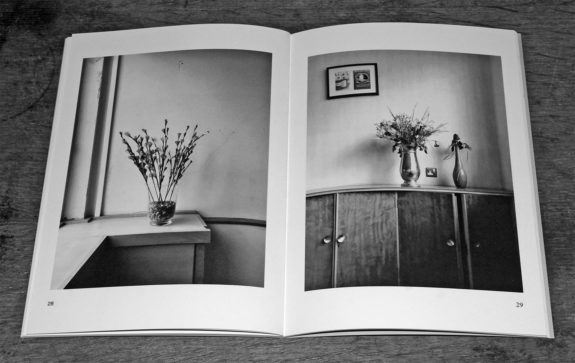

The film depicts the rural landscape as a starkly beautiful place, and imparts to the watcher a sense that they are viewing a place on which modernity has not yet fully encroached, a rural edgeland which is possibly also not quite as regulated as elsewhere. The opening scenes show a farm labourer setting off to drown unwanted kittens in a sack as birds caw somewhat menacingly, and the landscape is shown as being full of derelict and abandoned equipment and broken fences. Children appear to be able to roam freely and unsupervised wherever they want, whether amongst farms and their equipment, the fields or what may well be former mining and/or quarry areas.

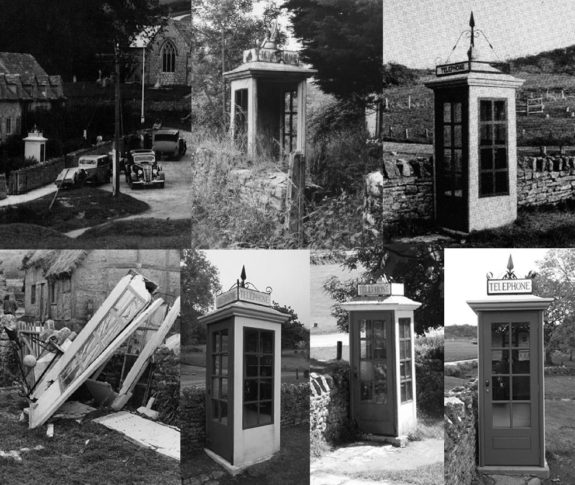

Day-to-day life as shown in the film feels very different and distant from today, and in various ways Whistle Down the Wind is something of a time capsule or snapshot of a previous era. For example there is a distinct lack of telephones in the local area; there is no phone on the farm where Blakey is hiding, meaning that in order to telephone the police to inform them that Blakey is hiding in their barn, the children’s aunty has to run into town. Once there her first attempt is thwarted as it is half-day closing at the shop she tries, a retail practice which also very much roots the film in a previous era.

This distance from contemporary British mores is also depicted in terms of how religion and religious beliefs are very widespread and an inherent part of life for much of the population, in particular in terms of the depiction of children’s beliefs and their open and devout acceptance of religious stories; based on little evidence the eldest sister Kathy comes to believe that Blakey is Jesus, and sets about shielding him from the adults, stealing food for him and essentially acting as a religious gatekeeper or apostle in the way that she allows or keeps the other children from him, while also stoking and ensuring their belief in him being Jesus Christ.

Also the way in which the children are left to play and roam the countryside, town, formery quarry/mining areas, railways and amongst farm buildings and equipment almost completely unsupervised provides a marked contrast and distance from contemporary times, and what has come to be known often disparagingly as helicopter parenting (a phrase which implies an overprotective and excessive interest in one’s children). There is a sense in Whistle Down the Wind that the children are free to create their own worlds and world vision, which may well be quite separate and at odds with the adult world and reality, and not without danger.

This connects with Andy Beckett and Roger Luckhurst’s comments in The Disruption, a booklet length discussion inspired by 1975 post-apocalyptic and at times mystical children’s television drama 1975, in which they say that “One of the strengths of The Changes is the way it makes childhood seem both frightening and incredibly exciting, almost limitless with possibilities.”

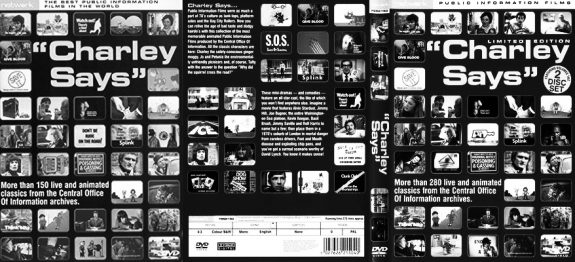

They also comment that the government-commissioned public information films which were broadcast on television regularly and extensively in the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s were in part a reflection of the freedom without adult supervision that children enjoyed during this period, which meant they needed to be warned about the dangers of railway tracks, electricity substations, farms, factories, predatory strangers and so on. In some ways watching Whistle Down the Wind with a contemporary mindset that dangers can lurk round every corner, the film can seem almost like a custom made piece of propaganda for the importance of public information films.

(As an aside, public information films were provided free of charge to broadcasters for them to use whenever they wished. Part of the reason they were broadcast extensively was that they were useful as a cost-free way of filling the gaps in fixed-duration commercial breaks when sections of advertising airtime had remained unsold. Along with their often ominous and unsettling qualities, the accidental side product of their frequent broadcasting due to this commercial usefulness may well how deeply ingrained they are in the minds of those who grew up watching them, and who subsequently have come to view them as hauntological cultural inspirations and totems.)

Tonally it is an oddly multi-layered and ambiguous film; on some levels it is almost archetypal family viewing, full of childhood wonder and exploration, while on others it can be read as somewhat darker toned, as essentially the children befriend, aid and are in awe of a man wanted for murder.

Also, the film appears to be ambiguous to a degree in terms of Blakey; he is not painted so much as an out-and-out villain, more just a bit of a “wrong un”, and he is shown as a desperate man who somewhat manipulatively takes advantage of an opportunity that is presented to him. The background to his alleged crime is not given in the film, so it is not revealed if it was in self-defence or had other mitigating circumstances. However he has hidden a gun, which was possibly the murder weapon, and the possession of firearms would have been something of a rarity in 1960s Britain, and this implies that he was very much involved or embedded far away from the right side of the law and conventional life. Possible viewer ambiguity or even sympathy for him is, however, greatly tested when he sends Kathy to fetch the gun, albeit she does not know what it is, and he tells her not to look inside its cloth wrapping.

This sense of ambiguity about a man on the run and his being aided in a rural setting by a child who has lost one or more parents has parallels with Charles Dickens’ novel Great Expectations (1861), which has been repeatedly adapted for film and television. In the novel an escapee convict called Magwitch is stumbled upon and subsequently aided by a young orphan boy called Pip. However, rather than as in Whistle Down the Wind it being due to severely mistaken identity coupled with religious belief, in Great Expectations Pip initially helps Magwitch due to intimidation and fear.

As with Blakey in Whistle Down the Wind, Magwitch is also shown to be not purely villainous, as when he has found his fortune abroad, as a thank you for his help, he becomes Pip’s anonymous benefactor and enables him to move to the city and become a gentleman. Further layering the sense of ambiguity in the story, Pip’s new-found prosperity causes him to lead a somewhat aimless decadent lifestyle, overspend and acquire heavy debts, and later in the novel, after discovering Magwitch is his benefactor, he attempts to help him once again avoid capture, this time acting of his own free will.

Religious allegorical aspects recur throughout Whistle Down the Wind, some of which are more obvious than others. For example, in one scene an older teenage tough mocks and bullies a younger boy into denying he has seen Jesus, which he does three times, after which a train whistle is heard. This is analogous with the story in the Bible of Apostle Peter denying Jesus three times, which Jesus had predicted he would do before the rooster crowed. That this is religious allegory requires very observant watching of the film, coupled with a reasonably in-depth knowledge of stories in the Bible. Elsewhere, when Blakey is frisked after giving himself up to the police and he holds his arms outstretched, it is potentially easier for the casual viewer to detect the allegorical nature, as it quite clearly connects with the widely known iconic religious imagery of Jesus’ crucifixion.

The film’s allegorical content is also made fairly explicit, or at least hidden in plain view, in the credits, where the early core group of children who visit Blakey are called The Disciples, a reference to them numbering a dozen, as did Jesus’ disciples in Christian theology.

Kathy observes his capture and stance during frisking, and it seems to confirm her belief that Blakey is actually Jesus Christ, and the adults and police officers are merely repeating the previous Biblical persecution of him. She continues to maintain her unshakeable belief throughout the film, despite him doing nothing that could possibly confirm that belief. It is possible that alongside a religious connection, she is also seeking some kind of connection, guidance and attention from an older adult figure, no matter who they are; her father is constantly busy with his farm work, and as mentioned previously her mother has died, and she is being in part brought up by an aunty who lives with them, who is something of a shrew and makes little effort to hide her dissatisfaction with the situation, her familial duties and the behaviour of the children.

There is also a sense that the children are coming to the realisation that adults do not fully understand, nor are able to provide convincing explanations for how the world works and/or God’s will. This is highlighted when Blakey has let the younger brother Arthur’s kitten die, having given him it as he believes Jesus will care and provide for the creature, as a Salvation Army officer had told him that was what Jesus would do. Arthur and Kathy set off to find a priest and ask him why God and Jesus would let the creature die. In a cafe the priest looks somewhat awkward at having been put on the spot, and tells them that as babies are being born all the time, we’ve got to make room for them. As they leave the cafe Arthur matter-of-factly says “He doesn’t know does he?” and Cathy can only shake her head.

The manner in which children are portrayed at times presents them as having a threatening group mentality, and this is coupled with the aforementioned sense that they are not subject to constant adult supervision, and also operate and have effective communication networks that exist outside of the adult world. This mob mind and threatening aspect is particularly pronounced when the first group of children outside the brothers and sisters visit the supposed Jesus in the barn, and they surround him and chant oppressively and demandingly for a story. This is a sequence which is difficult to watch without it conjuring up images of the children in the 1960 film Village of the Damned, in which alien children in human form are implanted into and aim to take over a small village, acting as a holistic hive-like mob, and utilising a form of telepathic group think to do so. This connection may be made in part as in both films the children have a near uncontrollable nature, a forceful and unrelenting way in which they make their demands, and both also feature isolated rural settings, and were made at a similar time, and so share some similar period aesthetics.

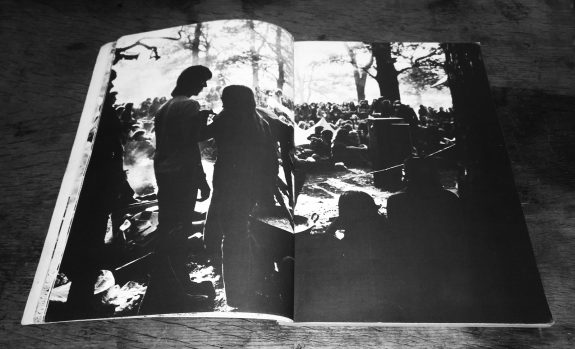

This potentially uncontrollable mob nature of the children is also present when Blakey is finally surrounded by the police, and dozens of children, perhaps the best part of a hundred, swarm to the site over the fields. They have been summoned by Kathy through some mysteriously highly efficient and fast acting network of communication, and even with foreknowledge through previous viewing that it is not the case, there is a palpable threat and tension to this massing of children, which leaves the viewer questioning whether they will join forces to overpower the adults and allow their messiah to escape.

Kathy’s belief that Blakey is actually Christ remains undimmed to the very end, and this is demonstrated in an almost final scene when two small children approach Kathy and ask her “Has he gone?” She replies “Yes, you missed him this time. But he’ll be coming again”, implying that she believes that what has occurred was merely one cycle in a series of Christ’s resurrections.

After having previously fiercely fought with him to prevent Blakey’s capture, the final shot shows her father putting his arm around her and they walk off to the farm together. This leaves the viewer with a decided unresolved nature to the story, as although Kathy has acquiesced to his fatherly comforting, her future is likely to involve much confusion as she battles with her belief in Blakey being the messiah and that his capture was merely a repeating of Christ’s persecution in ancient times, alongside the reality that is likely to be presented by the adults in her life, newspapers and so on that he was actually a man on the run who had been accused of murder.

But I shouldn’t leave the reader with a sense that Whistle Down the Wind is unrelentingly bleak and dark, or grittily realist. Far from it. It is highly entertaining, moving, tender, and at times very humorous, and the realism is very much intertwined with a sense of magic realism. Much of the humour comes from Charles, the youngest sibling, who has a forthright Northern bluntness to his manner which at times is laugh out loud funny. It is a film full of memorable, funny and poignant moments and images.

These include when one of the sisters brings Blakey the wonderfully ill-suited, and useless to a wanted man on the run, gift of a young girl’s magazine/comic, with her pleasedly pointing out that it contains an Arabian charm bracelet as a free gift. The only response to this he can think of is just to say “Very nice”, and it leads to a noteworthy sequence when he subsequently chooses to read to the children a story from the magazine of an air steward, rather than reading from the copy of the New Testament they have brought him, as they expect him to. The children don’t seem to really mind, they merely appear to be enjoying having a story read to them, and for a brief moment the incongruity of the situation almost melts away. Another time, before he has realised they think he is Jesus, Kathy gives him an illustrated postcard of Jesus in Biblical times. He is bemused by why she has given it to him and with disarming naivety and accidental humour she says “It’s a picture of you. Course it was taken a long time ago.”

Towards the end of the film, when he is cornered in the barn by her father and the police, Kathy sneaks off to talk to him through a window hole, and she brings him some cigarettes (“snout”) that he had earlier asked for in a very un-Christ-like manner. He knows that his time is up, and in the style of a condemned man enjoying one last moment he puts one of them in his mouth, only to realise that Kathy has not brought him any matches. There is a certain quiet prosaic tragedy to this moment, a humanising of Blakey amongst the high drama of the situation and the unreality and unsustainability of the world and belief the children have created around him.

As a final note: at the time of writing Whistle Down the Wind only seems to be available on DVD and hasn’t been released on Blu-ray (in the UK or internationally). Also, as far as I know, it hasn’t had a widespread digital release. It is available to stream in high definition at the ITV and BBC joint streaming venture Britbox but, and I don’t know if this was a temporary glitch, when I last viewed it there the quality looked nearer to an upscaled standard definition version rather than a pristine HD restoration.

All of which seems like something of a shame, as the black and white visuals in the film, particularly the landscapes, are very striking and I expect would very much benefit from a sympathetic high-definition restoration.

Links:

Elsewhere at A Year In The Country: