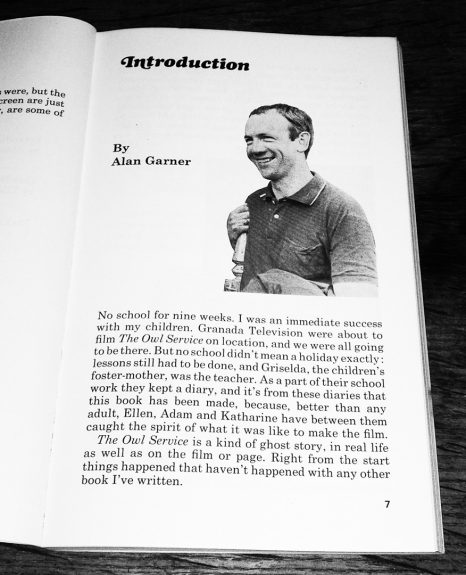

With the festive season having only fairly recently passed and it still being the New(ish) Year, I thought I would write about some festive television.

In particular Mackenzie Crook’s modern-day adaptation of Barbara Euphan Todd’s Worzel Gummidge books, that were originally published between 1936 and 1963. Crook wrote, directed, starred in and was one of the producers of the new two-part mini-series, which was broadcast by the BBC on the 26th and 27th December 2019 (and apart from Christmas Day and Eve, you couldn’t really have a much more festive time slot).

Set in the British countryside, the story involves two children called John and Susan who have been living in care and are very unused to rural life and its lack of technology (cue their phones being lost, broken and not being able to charge them as they connect with rural life), who travel to a farm called Scatterbrook for a holiday. They stay with a farmer and his wife, and in one of the farm’s fields they meet Worzel Gummidge, who is a living, sentient scarecrow with a turnip head, and conker brain, who is able to walk and talk. According to scarecrow lore Gummidge is not supposed to talk to human’s but because of what he describes as their mismatched ways of dressing (which are vaguely gothic and urban casual) he thought they were scarecrows. The children and him become friends and embark on adventures in the countryside together, as they are called upon to save a magical tree, restore the seasons which have become stuck and do battle with a gang of wannabe-biker tough-guy scarecrows (!)

Along the way Worzel also meets up with Aunt Sally, an ex-fairground doll who, as with Worzel, is alive and sentient and who, rather than his bumbling friendliness, has a somewhat snooty demeanour, and he also tries to enter himself in a competition amongst non-sentient scarecrows made by children, which takes place at the “big house”, the local mansion owned by Lady Bloomsbury Barton (which is subsequently infiltrated by the wannabe-biker scarecrows).

The series has been adapted for television before, including a four-part series called Worzel Gummidge Turns Detective broadcast in 1953, and Gummidge was also played by former Doctor Who Jon Pertwee in the 1979-81 series Worzel Gummidge, with him reprising the role for a Television New Zealand and Channel 4 co-follow up series that ran for two series in 1987 and 1989, and which relocated the story to New Zealand. Pertwee’s Gummidge, with his besoiled face, straw sticking out of his sleeves and interchangeable heads which gave him different abilities is somewhat iconic, as is his femme fatale in the series Aunt Sally, who was played by Una Stubbs. However, Mackenzie Crook has said that he didn’t see that version as a child and he did not view it before working on his, with him saying that:

“I had a very clear idea about how he wanted it to unfold. I thought it was right to knit in environmental issues, not in a way that is preachy but in a way that children would understand the context of the stories… Worzel is part of a dying [i.e. traditional rural ways] England but he has a message which is incredibly relevant for today… That was one of the main reasons I wanted to do this and why I want to carry on with more series.” (Event magazine, 15/12/2019)

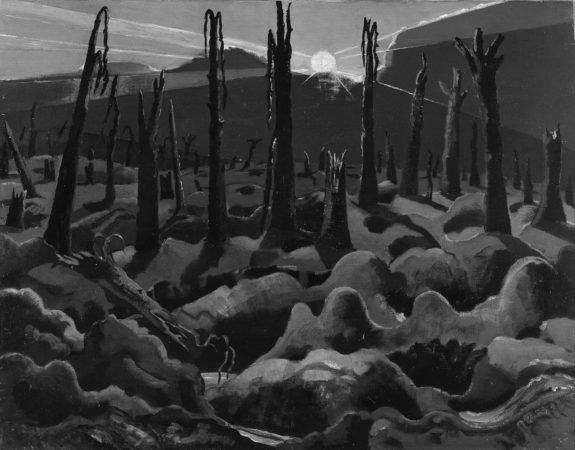

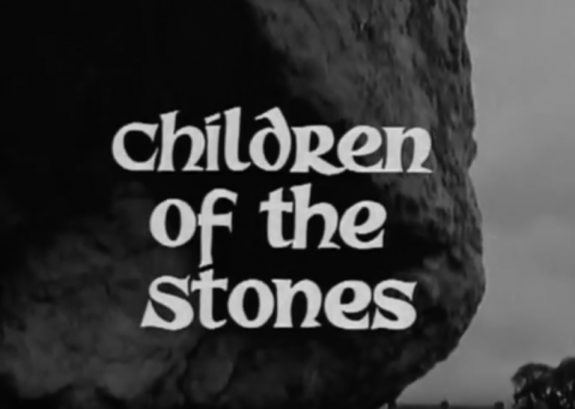

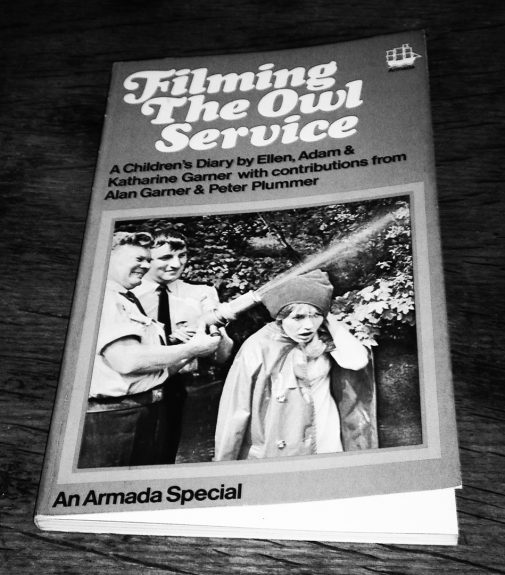

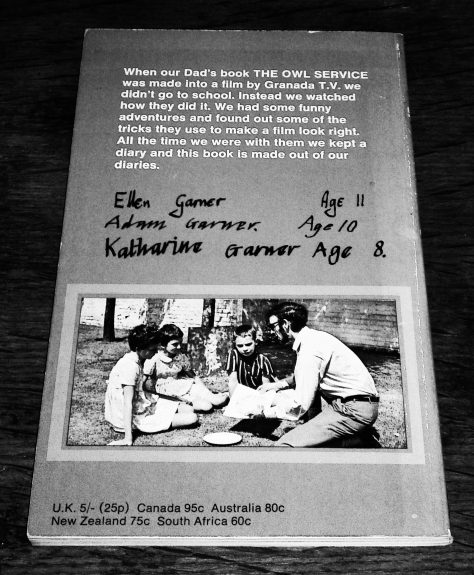

Just as some of 1960s and 1970s British children’s television, such as The Changes, Children of the Stones and The Owl Service, that was somewhat odd in terms of atmosphere and themes etc, particularly considering its intended audience, has been repurposed as hauntological and wyrd / otherly folkloric touchstones and inspirations, Crook’s Worzel Gummidge could be considered to be a further repurposing, taking that 1960s and 1970s source material and recalibrating it for a contemporary audience. In a way, although the subject of his films is somewhat more adult, it put me in mind of the manner in which Peter Strickland’s films, including The Duke of Burgundy and Berberian Sound Studio, in part take as their inspiration European cult arthouse independent cinema from previous decades which often had left field, exploratory and sometimes transgressive or salacious subject matter and presentation, and recalibrates, evolves and filters it via his own aesthetic and cinematic vision for a contemporary audience.

Crook previously also wrote, directed and starred in the Detectorists television series that was broadcast by the BBC between 2014 and 2017, which centred around two friends who go metal detecting together in the countryside. Both the Detectorists and Worzel Gummidge are deeply imbued with a sense of pastoral bucolia and beauty, which is accompanied by undercurrents or flipsides; in Detectorists there is a sense that the landscape is layered with hidden and often lost secrets, while Worzel Gummidge adds a sense of magical folkloric goings on hidden in plain view.

Both series could be placed in a loose category of television drama that, in the A Year in the Country book Straying from the Pathways, I describe as “offering ‘glimpses of Albion in the overgrowth’, that is to say, mainstream dramas which to various degrees explore, utilise and express a flipside, or otherly pastoralism, and at times variously contain elements of, or are fully intertwined with folk horror.”

Due to those aspects being notably present in both Detectorists and Worzel Gummidge, Mackenzie Crook is beginning to create an otherly pastoral / wyrd folk body of auteur-like television work, and indeed to be one of mainstream British televisions prime proponents and creators of “Albion in the overgrowth”.

Both series, albeit more overtly in Worzel Gummidge, interconnect with some of the themes, atmospheres and iconography of folk horror but in a way that, although at times a little unsettling, sidesteps actual horror. Although generally Detectorists is fairly realist in tone, one episode features a timeslip sequence, where the history of the landscape melts aways and then is relayered under the watchful, prescient eye of magpies. Although the sequence is not overly dark, there is something subtly unsettling about it, perhaps in part because the magpies have a slightly ominous air to them, and also possibly because of the use of music by The Unthanks to soundtrack the sequence (who also created the soundtrack for Worzel Gummidge), which is a lush, fecund reinterpretation of traditional folk intermingled with traditional and children’s rhymes, and is both accessibly melodic and also subtly hints at a sense of the “otherly” or “wyrd” in folk and pastoral orientated work.

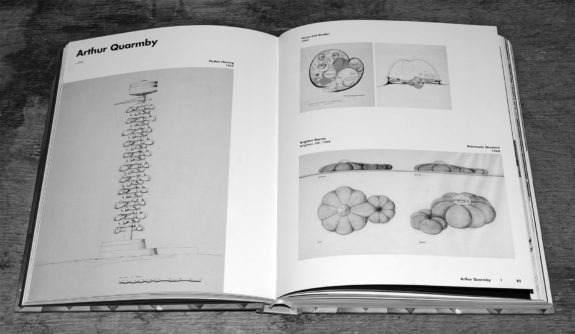

(Above left-right: one of Mackenzie Crook’s sketches for the show and Arthur Rackham’s Tree Talks to Scarecrow)

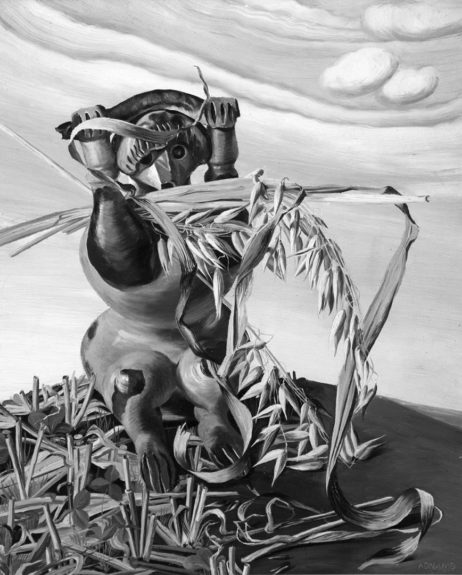

The design of the scarecrows draws heavily from sketches which Mackenzie Crook made when he was making the series (and also, possibly subconsciously or coincidentally, some of the “pirate as rock’n’roll rebel” stylings of the Pirates of the Carribean films released in 2013-2017, which he has appeared in):

“[Worzel Gummidge’s] look occurred to me almost immediately, and that’s why I was suddenly into [making the series] – the idea that he wasn’t stuffed, but just clothes hanging on sticks… I was thinking of Arthur Rackham’s illustrations – they’re very dark and gothic… Early on, I had an idea that he had an old military redcoat that he found in a barn, like in an old soldier’s chest – and had a robin in his pocket [where his heart would be]… Most writing days I would start off by just drawing a scarecrow… I wanted them to look domestic, as if they’d been built by someone out of odds and ends.” (Mackenzie Crook, interviewed in The Telegraph, 21st December 2019)

Crook goes on to say in the interview that although Worzel Gummidge looks alarming, “as a scarecrow is supposed to” but that as soon as he smiles and says “Welcome to Scatterbrook” that hopefully this aspect is dispelled and that there’s nothing dark about the show. He comments that it’s tone is closer to the rustic potterings and gentle comic relief of Detectorists. However, in his version of Worzel Gummidge the scarecrows often have not just an appearance but also instill an atmosphere that would not seem out-of-place in a folk or other horror film; many of them are friendly but they could just as easily be bogey men. Gummidge himself is somewhat reminiscent of iconic horror film character Freddy Krueger, with both having long pointed fingers, red and black tops/coats, black hats and skin with a not dissimilar wrinkled appearance (albeit Krueger’s is due to damage rather than the natural texture of a turnip).

Francesa Mills plays a diminutive, older female scarecrow called Earthy Mangold whose clothes and face are made from sack cloth. Earthy Mangold is actually a warm, maternal character but there is something about her sack cloth face (which is very well done, tip of the hat to those who worked on the design, makeup, SFX etc) and short stature that is unnerving. Perhaps in a in some oblique way she is reminiscent of another iconic horror film character, the murderous doll Chucky? Adding to some viewers expectations that the series would take a darker turn is the presence of Steve Pembridge as the farmer, who previously appeared in and co-created the comedy horror radio / television series and film The League of Gentleman (1997-2017) and the black comedy / horror anthology series Inside No. 9 (2014-), both of which at times had notable folk and/or other horror-esque aspects.

Add to all that night-time borderline grotesqueries silhouettes of the scarecrows cavorting across the landscape and the way in which much of contemporary film and television is quite dark and/or violent and, despite the series being family viewing, it is a series where the viewer could be forgiven for half expecting the scarecrows to turn bad and say, go on a murderous spree (!) Thankfully, they don’t… but still, at times the series feels like a friendly nightmare, and has an air of unsettling unpredictableness, which is heightened by the scarecrows often having a chaotic, unfettered by convention air to them, particularly when they are gathered together.

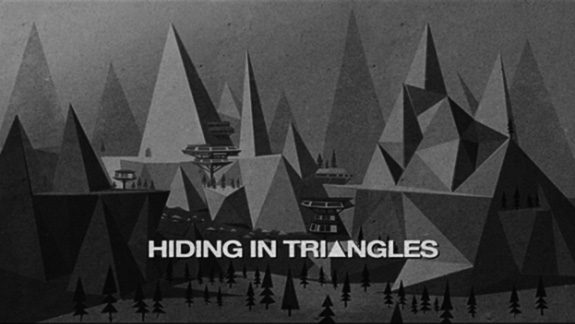

This unpredictable air takes a turn for the worse when Soggy Boggart arrives, who is the leader of the aforementioned scarecrow wannabe-biker gang, who have never actually been on a motorbike. They tear around the countryside causing trouble, pretending to be on their motorbikes, which are actually merely sections of handlebars or home-made pseudo-motorbikes and scooters, and are closer to children’s toys than the real thing. Soggy and his gang present themselves as ruffians and bad boys who only drink fizzy drinks, which in scarecrow culture appears to be the equivalent of drinking alcohol in order to denote its imbiber as being tough and hard.

Stylistically their leather, cut off and painted jackets are reminiscent of British bikers from the 1950s to 1970s such as Ton-up boys and café racers, and also the undead bikers of the 1973 film Psychomania. Alongside this their style also has aspects of American biker and rock’n’roll culture, but in an archetypal manner that recalls the Swiss rebels of the 1950s and 1960s photographed by Karlheinz Weinberger, who reinterpreted their US source material and inspiration in a heightened and almost surreal manner, as though they only knew of it via the dreamscapes of a fading in and out television signal.

All the gang, as does Worzel Gummidge, have heads made from vegetables, and Soggy has an Elvis-style quiff perched on top of his long marrow-head, the comic and conflicting nature of which somewhat undermines his desperate wish to be a stylish bad boy (he keeps insisting that his name is Harley Davidson and gets riled when anybody calls him Soggy).

Worzel seems wary of Soggy and his gang, perhaps a little afraid, but not all that much and at one point it looks like there’s going to be a rumble between him and them. This doesn’t happen as Earthy Mangold arrives and she talks of how she used to babysit for Soggy and how he wore teddy bear pyjamas and that she knows all their mothers and what would they think? In the face of a “grown up” from their childhood the gang are immediately reduced to apologetic, meek penitents, their bad boy intentions forgotten and swept away, and along with Worzel and the children they set to washing the graffiti ‘swears’ they have painted on the sides of the farmer’s cows. In one of the many humorous moments in the series these ‘swears’ are gloriously inoffensive and funny and include the likes of “Horse” and “Cud mucher”.

And, despite my above comments about the potentially darker tinged aspects of the series, overall it is light-hearted, humorous and tender, and works on a number of different levels to be true all-ages family viewing.

As referred to in the quote by Mackenzie Crook above, the series tackles ecological issues. Soggy Boggart and his gang leave a trail of meal deal-like sandwich packaging, bottled drinks etc litter behind them in the countryside, which Worzel and the children try and pick up, and this marks the gang out as not so much nonchalant tough guys but rather negligent and misguided fools at best.

At one point the children and Worzel convince the crows, who are his natural adversary, to remove and recycle the plastic bags which have become entangled in the branches of a magic tree, causing it to become unwell. The seasons have also become stuck, meaning that harvests are not ripening, flowers are not blooming and so on. Although the reason for this is not given an overtly ecologically themed explanation, or in fact overly explained at all, other than it being said that it happened before, being placed alongside other more overt ecological issues in the series, the potential problems it poses place it quite firmly amongst and alongside contemporary ecological issues and concerns.

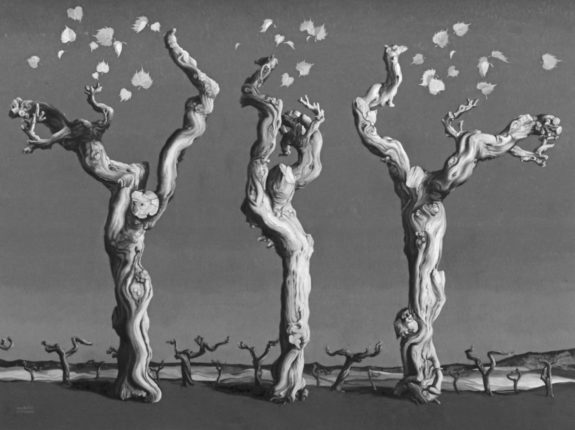

The seasons are said to be locked and they must be unlocked by the use of a key and Worzel needs to gather together himself and other scarecrows in order to solve the problem (the magic tree sends out his message to them on the wind, which it could not do when it was in poor health due to the plastic bags in its branches). This “key” turns out to be a magical pattern on Worzel’s handkerchief, with the pattern’s shape being that of a helicopter style tree seed, which are also known as keys. This leads to some of the most otherly or magical aspects of the series, when the gathered scarecrows dance and twirl through the fields, as the seed keys do in the air, in order to recreate the magical pattern in the crops, in a manner reminiscent of crop circles. Once created some of the circles amongst the pattern gently rotate under their own power, and the following day, with the seasons unlocked, crops are shown as ripening and turning golden in a matter of seconds as the change flows through the land, flowers bloom fast enough for the eye to see and so on.

Interwoven amongst this is the series’ trademark humour and details of how the scarecrows’ well thought out world works; once the seasons have been unlocked and the harvests have been able to be collected, the crows receive their reward for clearing the magic tree from Worzel and the children, which is a bag of grain. Once they’ve “enjoyed” this Worzel, who can talk with and summon birds, humorously tells their leader that they’re not friends, and gives them scant seconds to scarper and get their filthy talons off his land. They rapidly fly off and the common antipathy and co-dependant balance and struggle between farming and nature is once again restored, and Worzel can get back to working as a scarecrow. Although he may seem at times bumbling, a bit daft and something of a tender hearted softie, Worzel is no easy mark when push comes to shove; although initially seeming scared by him, when he was threatened by Soggy and things looked like they might turn more serious he seemed perfectly prepared to stand his ground.

The series is full of other sections which give an insight into the scarecrows’ lives and characters. In another humorous and this time also somewhat charming sequence, with a degree of hubris (which is part of his character, as he somewhat boastingly thought he would definitely win the scarecrow competition mentioned earlier) Gummidge flourishingly mimes for Earthy Mangold his going through a door at the “big house”. She finds it astonishing, hilarious and hugely entertaining, exhorting him to do it again but this time to mime pulling rather than pushing the door, what with such things being so out of the realms of day-to-day life and possibility for scarecrows.

None of the magical aspects of the series – the way the scarecrows are sentient and alive and so on – are commented on nor explained. They just are, and are present in an otherwise normal, realistic world, in a magical realism manner. Although, as is often the way in such children and family orientated fantasy orientated fiction and drama, the magical aspects of the world are hidden from view from the grown-ups (Worzel generally goes into what he calls a “sulk”, when he goes stiff and returns to being a normal scarecrow, if he realises any adult humans are likely to observe him).

In the above interview with The Telegraph, Mackenzie Crook talks about this intersection of the day-to-day and the extraordinary and how he can trace his related interest in the “myth, lore and history” of the English countryside to Jez Butterworth’s play Jerusalem, in which Crook performed alongside Mark Rylance:

“The whole play was about English identity, rural identity, and I’d been fascinated by that since. As well, the stories I’ve always been fascinated by are about a very ordinary world where something extraordinary happens… Mark Rylance is massively into crop circles, and as an end-of-run gift he enrolled us all in a crop circle society, so we got quarterly newsletters about them. [Said very much tongue in cheek] It was all very mystical.” (Mackenzie Crook, interviewed in The Telegraph, 21st December 2019)

The scarecrows in Worzel Gummidge are created and loosely ruled by the The Green Man, who is the keeper of scarecrow lore and the mystical spirit of the countryside. His character and presence is one of the most overt connections with ancient folklore and myth in the series, in part because his name is, I assume, taken from Green Man sculptures, which generally depict a face surrounded by or made from leaves. These sculptures have been found in many different cultures and ages throughout the ages and have primarily been interpreted as being symbols of rebirth and representing the cycle of growth each spring. (The name Green Man is thought to stem from an article by Lady Raglan called “The Green Man in Church Architecture”, which appeared in a 1939 issue of The Folklore Journal.)

As with the scarecrows, the truth of who and what The Green Man is are hidden from the “real”, adult world, who think he is merely a traveller who passes through from time to time and mends damaged fencing hedges without wishing for payment.

The Green Man wears worn clothes, a charm round his neck, has a heavily lined face, large grey beard and unkempt dreadlocks with moss in them and is bestrewn with leaves, with the overall effect conjuring elements of ancient druid, mystic sage, an older member of the crustie subculture and a roaming tramp. He is played by actor, writer, comedian and traveller Michael Palin, who is one of the creators of the innovative and surreal Monty Python comedy sketch series which was broadcast on the BBC between 1969 and 1974. His presence in the series seems to add a certain cultural weight to it, and also connect it to a long-standing strand of experimentalism and left-of-centre work in British mainstream television (more of that please!)

(There is also another six degrees of separation from Monty Python, and indeed the classier side of British television comedy, and the 2019 adaptation of Worzel Gummidge, as in the 1980s series Gummidge finds double trouble in the shape of Aunt Sally II, played by Connie Booth who co-created classic British sitcom Fawlty Towers with Monty Python co-creator John Cleese.)

In the 1970-80s television adaptation of Worzel Gummidge, the character of The Green Man is known as The Crowman and was played by Geoffrey Bayldon, who also played the starring role as the title character in the 1970-71 British children’s fantasy television series Catweazle which adds a further otherly folkloric / hauntological television layering to Worzel Gummidge. Catweazle tells the story of an eccentric 11th-century wizard who accidentally travels through time to arrive in 1969 and is befriended by a young boy, who hides him from his father as Catweazle attempts to return to his own time. The series is particularly memorable for Catweazle’s mistaking of modern technology for a form of magic, with him calling electricity “elec-trickery” and telephones the “telling bone”. Although he looks more like a crazed or Rasputin-esque medieval monk, with his grey extravagant facial hair and mystical ways, his appearance and character are not all that removed from Palin’s The Green Man in Worzel Gummidge.

A further loose connection can be made to hauntological-esque television during a sequence in Crook’s Worzel Gummidge when John, one of the young children visiting the farm, is instructed by the farmer to somewhat hazardously climb amongst the beams and rafters of a barn in order to find the parts of a beehive. As he does so John nearly falls down onto various pieces of farm equipment and a barrel full of spiked implements (comically labelled as such), and when he needs light to see, the farmer throws him an already aflame cigarette lighter, which John subsequently drops amongst some dry straw – which fortunately does not set on fire. Consciously or not, this sequence appears to be channeling 1970s British public information films, which warned of the dangers of playing in “dark and lonely water”, flying kites near pylons etc and often had surprisingly dark atmospheres and presentation, and which have become ongoing hauntological inspirations and touchstones.

Worzel Gummidge ends with The Green Man and Worzel Gummidge talking as they sit overlooking a field. The Green Man has previously warned Worzel against talking to humans, saying that it is against scarecrow lore and that rather than gallivanting around he must stay at his post and continue his work, even warning him that the farmer is thinking of nailing him to his (literal) post, which puts an almighty fear into Worzel. However, Worzel successfully argues for the progression and evolution of scarecrow lore; he talks of how he is worried about nature, the flowers, the seasons, the bees, saying that they are all having a hard time but that maybe he can keep talking to the two young humans and they can begin to spread change to get things back on track. The Green Man asks him if he really thinks that just these two humans can really make a difference and Worzel says he thinks they can, which ends the series on a note of everybody being able to make a difference in terms of helping to protect the environment, despite them just being individuals or no matter how small their actions, and it manages to do this without an overly cloying, schmaltzy or by numbers manner, but rather in a heartfelt and touching way. Or as Michael Palin has said of the series:

“The environmental message is deftly woven in, so it won’t bash you on the head. It’s mainly just funny.” (Weekend magazine, 14th December 2019)

Links:

Elsewhere at A Year in the Country:

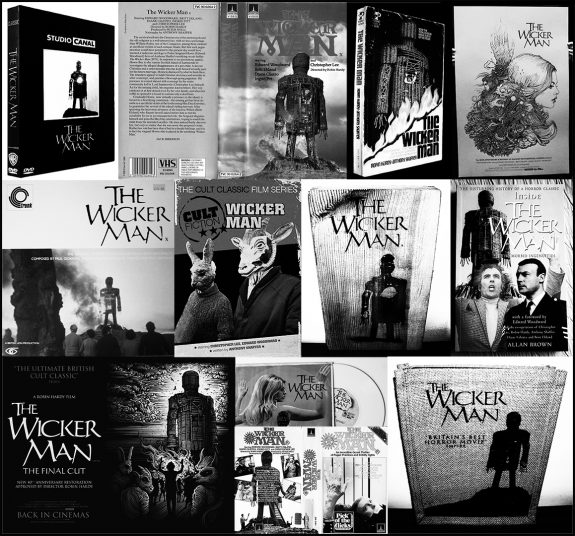

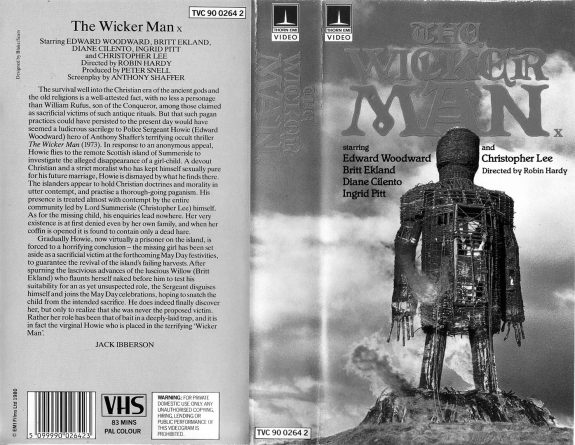

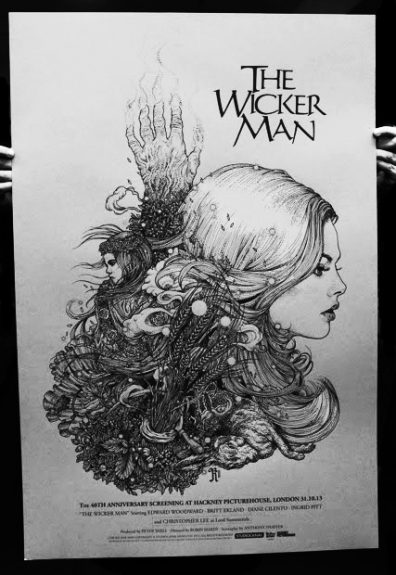

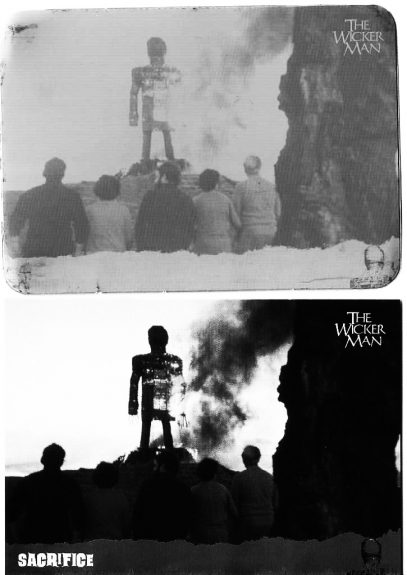

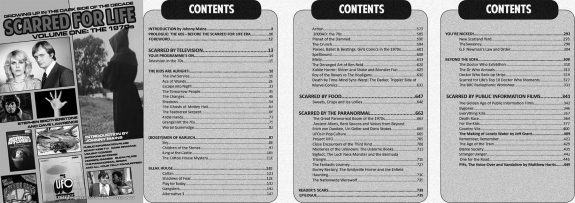

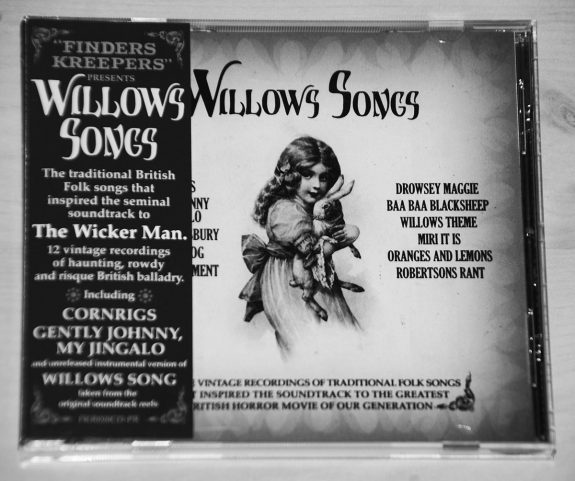

(Above: the 1998 Trunk Records release of the soundtrack which included a map of Summer Isle.)

(Above: the 1998 Trunk Records release of the soundtrack which included a map of Summer Isle.)