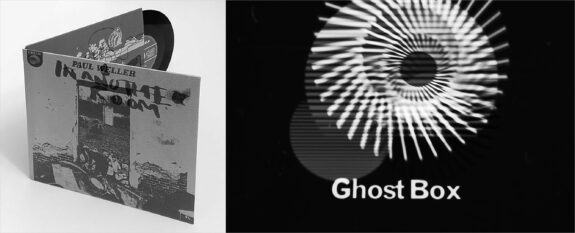

It may have seemed like something of a surprise cultural meeting to hear that in early 2020 Paul Weller, who has longstanding connections with mod music and culture, was to release an EP called In Another Room on Ghost Box Records, a label which is often associated with hauntology and that is one of the progenitors of such work.

However, looking back there have been all kinds of pointers towards the possibility of this collaboration happening – or at least points of connection between Paul Weller’s, Ghost Box’s and interconnected hauntological and “wyrd” folk or otherly pastoral work – that make it a lot less unlikely seeming that Paul Weller might one day collaborate with, to quote the description of Ghost Box on its website, “a record label for a group of artists exploring the misremembered musical history of a parallel world”. Below I discuss a few of those points of connection (but there are a whole lot more!)

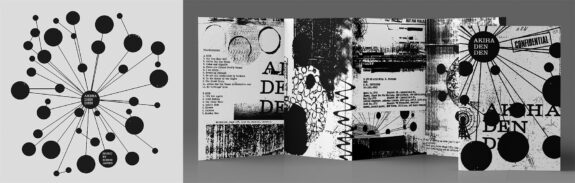

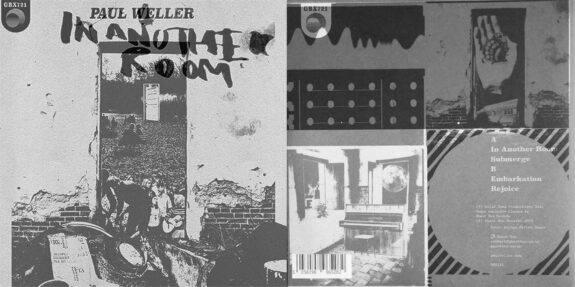

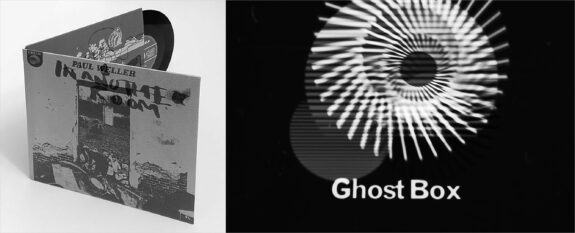

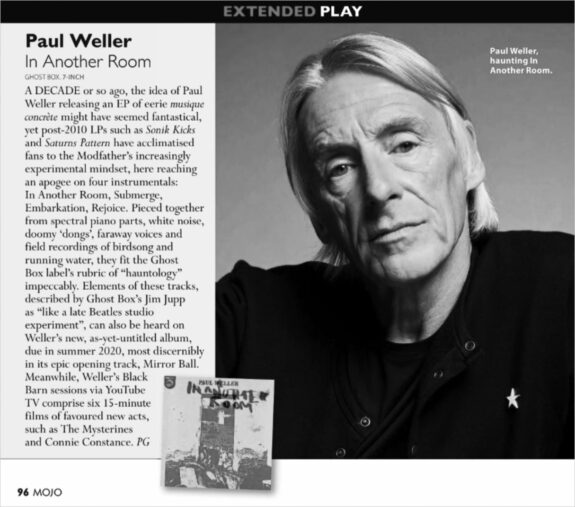

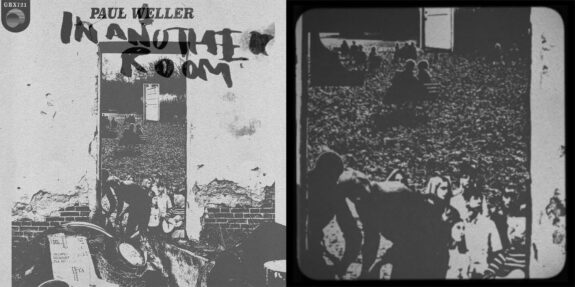

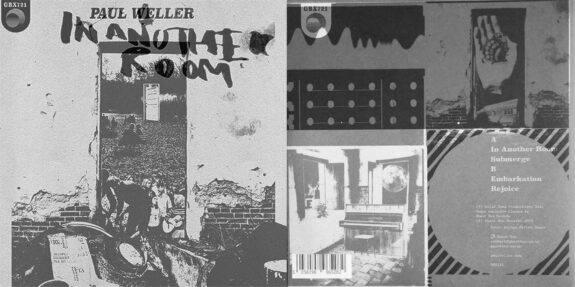

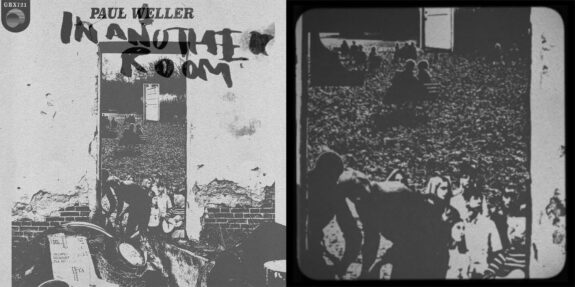

Although, as suggested above, Paul Weller is often associated with mod music and culture, one of the main things that has characterised his work has been exploring, combining and reinterpreting different musical styles and eras, and an associated exploring of unexpected tangents. His work at various times has eclectically contained and explored elements of punk, new wave, jazz, soul, electronica, funk, folk, psychedelia, prog etc, and his experimenting with hauntological-esque work that incorporated tape loops and field recordings on his In Another Room EP, which was released digitally and as a gatefold sleeve 7″ by Ghost Box, could be seen as being part of this lineage of exploring different cultural areas and influences, albeit in a more further flung reaches of culture manner.

Accompanying which, Paul Weller’s work often shares with Ghost Box and much of hauntological related work a sense of drawing from past eras, while at the same time not attempting to create a straightforward replication of them, rather it contains a reimagining and intertwining of different styles and times:

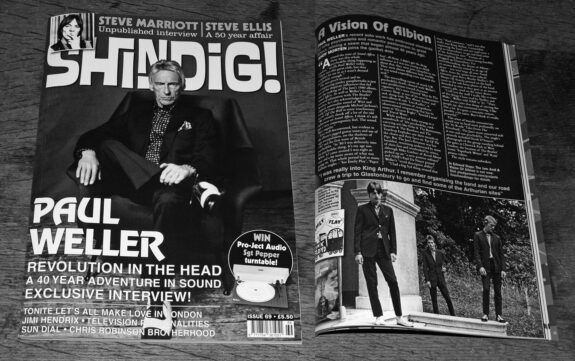

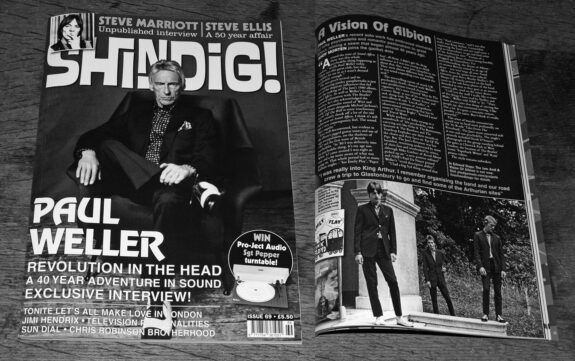

“[Iconic 1960s band] The Small Faces wanted to sound like Booker T & The MGs and they added another edgy thing to it. I loved all that. Why close yourself off to any one influence. Mod? The clue’s in the title innit?” (Paul Weller quoted from an interview with Jon ‘Mojo’ Mills, “Different Little Worlds”, Shindig!, issue 69, July 2017.)

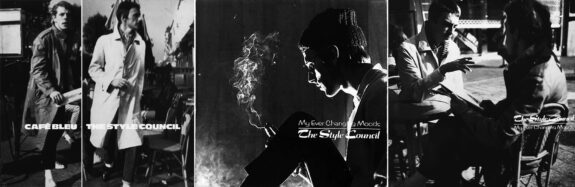

Also at times, as with Ghost Box, in Paul Weller’s work there has been a sense of parallel or imaginary world creation, particularly during his earlier years with The Style Council, the band he formed with Mick Talbot in 1982 after Weller’s previous band The Jam had split earlier that year.

Related to which, the mod cultural style or genre with which Paul Weller is often associated and has drawn inspiration from, has an inherent aspect of parallel world creation, one where the daily grind is kept at bay and escaped from by the creation of a subtly parallel world through meticulous attention and even obsession with clothes, style in general, music etc.

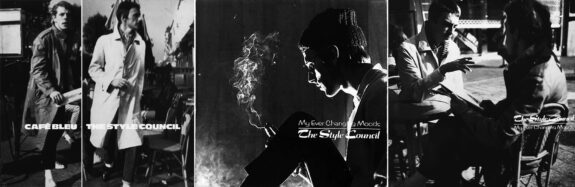

Paul Weller’s creation of an imaginary parallel world in his work found one of its peaks around the time of The Style Council’s first album Café Bleu, which was released in 1984. For this Paul Weller and Mick Talbot reinvented and reimagined the “clean”, sharp mod style and way of life and seemed to create a world unto itself by channelling a form of imaginary European New Wave-esque lifestyle and music which, amongst other areas, explored and created jazz and soul orientated music and sophisticated left-wing leaning pop. The resulting work seemed to be contemporary, belong to a time of its own and also, as with much of hauntological orientated work, draw from and reimagine some indefinable past era.

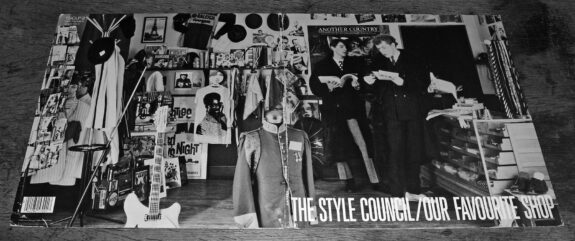

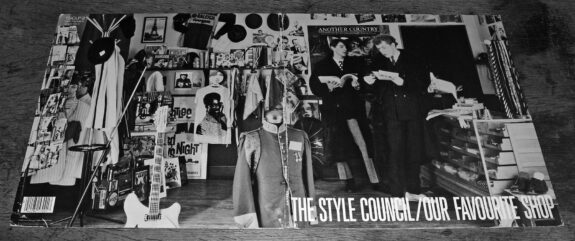

The gatefold cover image for The Style Council’s 1985 album Our Favourite Shop, to a degree, returned the band’s creation of an imaginary parallel world back to the shores of Blighty. The cover created and imagined a shop which was full of many of Paul Weller and Mick Talbot’s favourite things and cultural touchstones at the time, including albums, books, posters, magazines, clothes etc. The items for sale in the shop, its fittings and Weller and Talbot’s clothes draw from a number of different decades and styles, including that of a traditional British style shop or gent’s outfitters, and although the overall impression is one of being mod friendly, the cover and “shop” do not portray a collection of narrowly defined traditional 1960s mod reference points. Rather, as with the Café Bleu period of The Style Council’s work, it seems to draw from and reimagine some indefinable past and create a form of atemporal space or world of its own, one which exists separately to history’s timeline, and casts a spell over the viewer which may well convince them that somewhere in time the shop exists and is open for business, the bell above its door just waiting to sound as you step over its threshold.

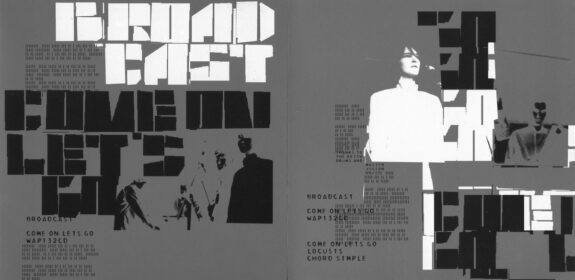

For a number of years preceding the release of his In Another Room EP, Paul Weller had mentioned in interviews that he liked Broadcast, a band founded by Trish Keenan and James Cargill, and which prior to Weller’s collaboration with Ghost Box had worked with the label and the associated The Focus Group (aka Ghost Box co-founder Julian House, who also created the majority of Broadcast’s artwork and worked on a number of their videos).

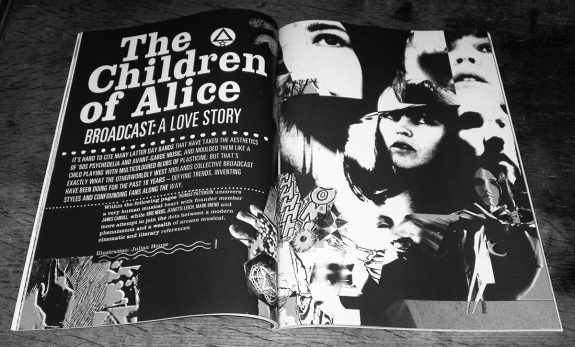

Broadcast share with Paul Weller and Ghost Box’s work a sense of drawing from and reimagining past eras and influences:

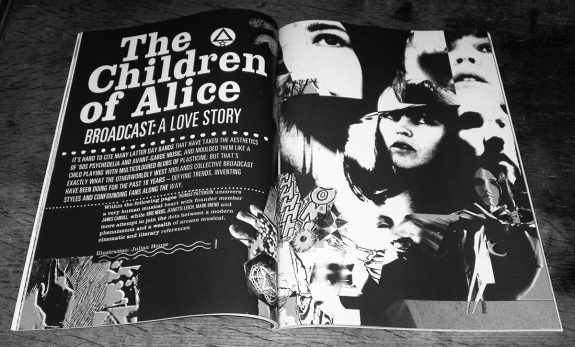

“It’s hard to cite many latter day bands that have taken the aesthetics of ’60s psychedelia and avant-garde music, and moulded them like a child playing with multicoloured blobs of plasticine: but that’s exactly what the otherworldly West Midlands collective Broadcast have been doing for the past 18 years…” (Quoted from “The Children of Alice, Broadcast: A Love Story”, Shindig!, issue 32, 2013.)

I wrote in A Year In The Country: Wandering Through Spectral Fields (2018), that the music Broadcast released is “both contemporary and also seems to belong to some separate time and place all of its own, with psychedelia incorporated in a manner nearer to an explorative portal then rosy-eyed nostalgia”, and Trish Keenan has said:

“I’m not interested in the bubble poster trip, ‘remember Woodstock’ idea of the sixties. What carries over for me is the idea of psychedelia as a door through to another way of thinking about sound and song. Not a world only reachable by hallucinogens but obtainable by questioning what we think is real and right, by challenging the conventions of form and temper. Bands like The United States Of America, White Noise, A To Austr and… The Mesmerizing Eye, all use audio collage, clashes of sound that work more in the way the mind works, the way life works, extreme juxtapositions of memories and heavy traffic noise say, or reading emails and wasps coming through the window. But as well, I feel that in my own small way I am part of that psych band continuum, but in a make-believe reality stemmed off to exist outside of the canon.” (Trish Keenan quoted from an excerpt of the unedited transcript of Broadcast’s interview with Joseph Stannard featured in The Wire issue 308, October 2009: “Unedited Broadcast”, thewire.co.uk, March 2020.)

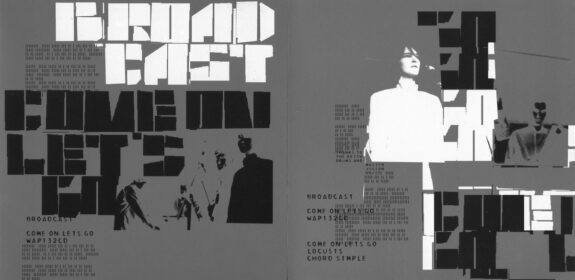

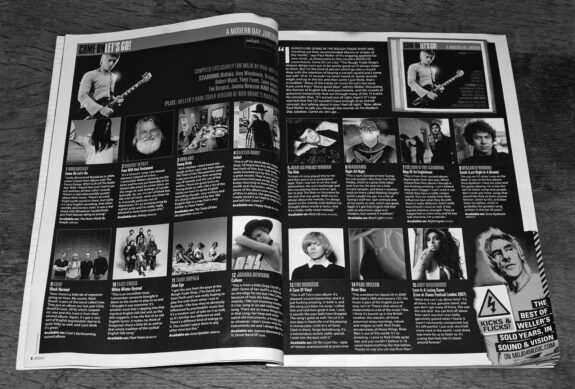

Paul Weller included “Come On Let’s Go” by Broadcast as the opening track on the cover CD he compiled for Mojo magazine’s April 2012 issue, a compilation which featured work by a number of different performers and took its title from the Broadcast track featured on it. In the accompanying notes for the CD he says that:

“I only discovered Broadcast in 2009, when I heard their album with The Focus Group, Witch Cults Of The Radio Age. Well, I heard that and I had to go out and buy all their other records. There’s a real otherworldly quality about their music. There’s an early Floyd synth sound in there, but really it’s very English sounding, that otherworldly electronica state.”

This sense of an “otherworldly” quality to Broadcast’s music could, in an oblique manner, be interconnected with Paul Weller’s work with The Style Council that is discussed above, particularly in relation to The Style Council’s creation of a world and time of its own, both visually and in some of the music on the Café Bleu album, which as suggested earlier is difficult to place as belonging to a particular era, and almost seems to exist in a dreamlike imagined world.

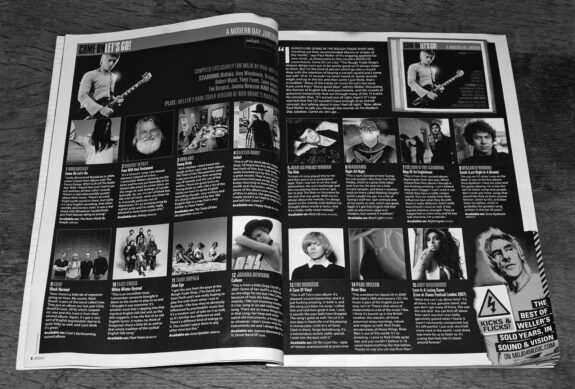

The Come On Let’s Go Mojo cover CD is described in the magazine as having “themes of English folk and psychedelia, and… moods of autumnal melancholy… [run] through many of the 15 tracks” and throughout his accompanying notes Paul Weller repeatedly references folk, psychedelia and other musical styles from previous eras when talking about the tracks’ atmospheres etc, but as referred to above in relation to The Style Council and Ghost Box’s work, there is a sense that one of the things which draws him to this work is that it is not a straightforward, purist or traditional replication but rather a cross pollination, reinterpreting and reimagining:

“[Diagrams’ “Night All Night” has] got that English folk feel with an electronic edge to it, modern but rooted in tradition… [Cow’s “Black Harvest” has also] got a very sort of English psychedelic feel to it, quite folky as well… [Fleet Foxes’ “White Winter Hymnal” is] another track that’s tapping into that mystical English folk feel and, as the title suggests, it has the feel of an old English hymn. It makes me think of Gregorian chant a little bit as well as that whole tradition of the cyclical English folk song… [With Tame Impala] they’re obviously influenced by psychedelic music but it’s a modern sort of take on it as well, so it’s familiar but different as well… [With Joanna Newsom’s work] I like not knowing whether it’s her song or an old traditional song… ” (Paul Weller quoted from his notes for the Come On Let’s Go cover CD, Mojo, April 2012.)

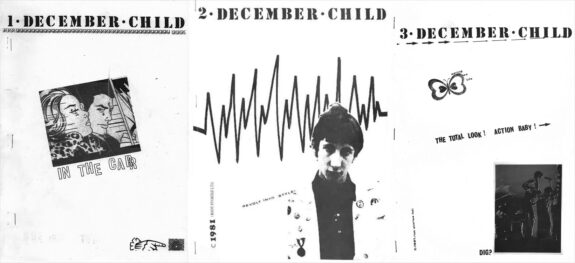

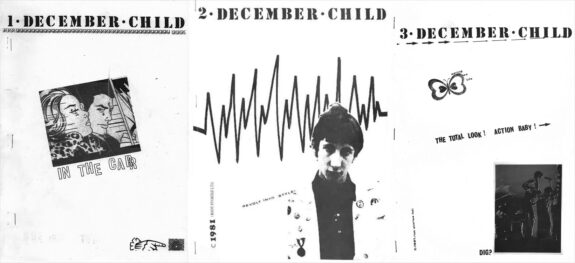

Interconnecting with such themes, are the pastoral aspects that have recurred throughout Paul Weller’s work, including in poems of his that were published in the early 1980s in the December’s Child fanzine, which was published by his Riot Stories publishing project:

“Weller’s poem, ‘In the Summer Months’, displayed a beautiful, pastoral innocence, its stanzas talking about ‘butterfly catching without nets’, and ‘boating on a lazy river’… while ‘Re-Birth’ [talked] about ‘country lanes’, ‘glistening sunshine’, set against the ‘volatile world of yesterday’… ‘Ten Times Something Else’ was… full of analogising, the final verse detailing ‘like a Sussex, summer field, with tall wheat’ set on a ‘country road, walking lonely but carefree’ [and] was redolent of the sort of bucolic landscape Weller enjoyed losing himself in.” (Quoted from “excerpt: in echoed steps: the jam and a vision of albion”, Simon Wells, 3:AM magazine, 13th March 2017.)

(As an aside, Simon Wells co-wrote with Ali Catterall the book Your Face Here: British Cult Movies Since The Sixties, which was published in 2002 and includes a particularly fine chapter on the 1973 film The Wicker Man, which as I have discussed elsewhere as part of A Year In The Country, has become somewhat iconic and influential with regards to folk horror and wyrd folk culture. I have something of a long-standing soft spot for the book, which is very accessibly written and for which the authors put in a fair bit of legwork by visiting filming locations, carrying out interviews etc, and I have written about it at the A Year In The Country site and in the A Year In The Country: Wandering Through Spectral Fields book.)

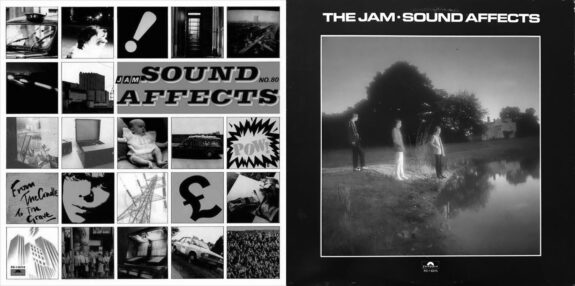

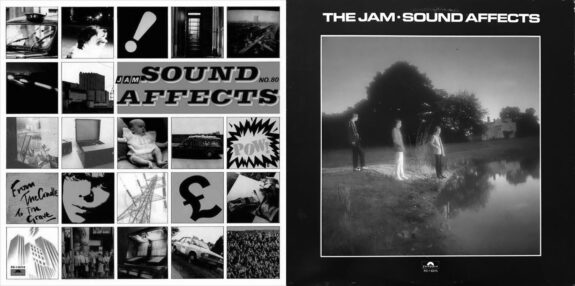

The pastoral themes in Paul Weller’s work and where he found his inspiration for them have at times sprung from and explored territory which also interconnects with wyrd folk and otherly pastoralism, with him being quoted in an article titled “A Vision of Albion” in issue 69 of Shindig! published in July 2017, which was written by one of the magazine’s editors Andy Morten, that around the time of Sound Affects, the fifth album by The Jam, which was released in 1980, he was:

“really into King Arthur. I remember organising the band and our road crew a trip to Glastonbury to go and find some of the Arthurian sites.”

Andy Morten goes on to write in the above article that:

“the [Arthurian] dream of Albion – an ancient Britain united in an age of peace – was writ large all over Sound Affects, from the quote from radical/romantic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley’s The Masque of Anarchy printed on the back cover to the soft focus photo of the band shrouded in mist as they gaze at an ancient country pile, used on the inner sleeve…”

Paul Weller’s Albion related inspirations at that time came in part from fairly esoteric sources:

“Weller would later admit, the main inspiration behind [the Sound Affects album track] ‘Set The House Ablaze’ [was] Geoffrey Ashe’s book Camelot And A Vision Of Albion. Published in 1977, Ashe’s book was not a bestseller, nor something that was referenced freely other than in fairly erudite circles. Ashe, a noted authority on Arthurian history, had drawn a line with noted English poets and visionaries through the centuries who’d attempted to decode the human condition – a continuum that had… stemmed from King Arthur’s vision of Albion. Assessing the quandaries that beset humanity over the ages, Ashe concluded that humanity had lost sight of its goals and had had its perception obscured and distracted via political or material obstacles, [and he concluded that] ‘Somehow human beings must recapture the lost glory in themselves, must transcend their present state if they are to change the world.’ Weller had come upon the book [via] his wide coterie of informed friends, and it clearly had a profound effect on him… ‘The ideas behind the Sound Affects lyrics were influenced by Ashe’s book,’ recalled Weller to the NME. ‘Which were we had lost sight of our goal as human beings, that material goals had hid the spiritual ones that had clouded our perception. There was also religious overtones. I suppose, on reflection, that the ideas are quite ‘heady’ and ‘hippyish’ but it was… a phase I was going through basically because of the books I was reading. Doors of Perception by Aldous Huxley was another – because they were concerned with mysticism and raising the spiritual and intellectual level of people.'” (Quoted from “excerpt: in echoed steps: the jam and a vision of albion”, as above.)

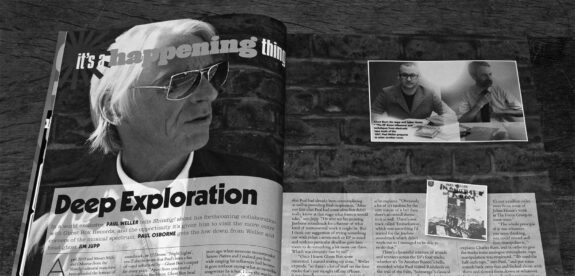

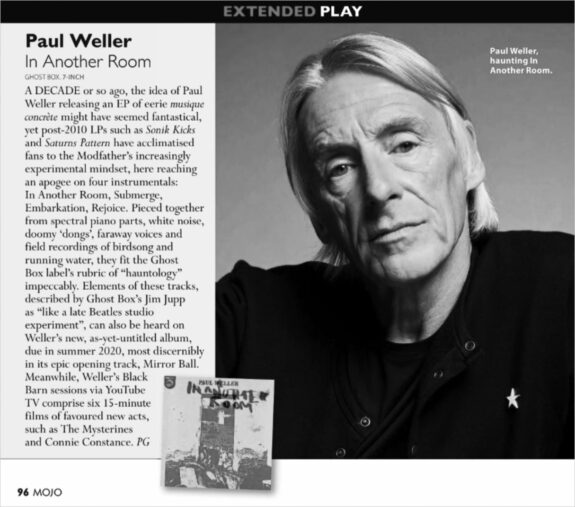

Other signposts which could be seen as pointing towards the possibility of Paul Weller working with Ghost Box, or at least ways in which his work intersected with Ghost Box’s, can be found in the abovementioned issue 69 of Shindig! magazine, published in 2017 prior to the release of In Another Room. In that issue during Andy Morten’s interview with Paul Weller it is commented on how the track “Green” from his 2012 album Sonik Kicks is a “textured piece, [which] showed the influence of Ghost Box’s haunted electronica”, and accompanying this in the interview Weller also expresses his appreciation for Ghost Box and Broadcast.

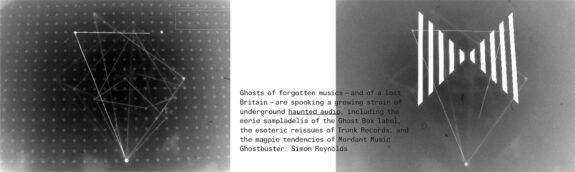

The strobing, hallucinogenic, geometric patterns, collaging of ’60s-esque and cosmic imagery in the video by Ruffmercy (aka Russ Mercy) which accompanied “Green” are not dissimilar to some of Ghost Box co-founder Julian House’s video work for the label, albeit in “Green” they are more mod-psych-pop art-esque filtered via digital artwork rather than seeming to be woozily abstract fragmented TV transmissions from a time you can’t quite place or remember, as is often the case with Julian House’s Ghost Box video work.

It was Shindig! magazine that provided the introduction and initial point of contact between Paul Weller and Ghost Box, which seems somewhat appropriate as the magazine draws from and covers past eras and musical styles which interconnect with a number of Paul Weller’s inspirations and reference points – including 1960s and 1970s psychedelia, pop, rock, soul, folk etc and contemporary performers who draw from and reinterpret such work – but as with Weller’s work, the magazine blurs the lines between years and genres somewhat, and at times wanders off into more tangential territory. At times this can include coverage of hauntological electronica and wyrd folk orientated performers, and those that have influenced and inspired them, including work released by Ghost Box and also some of the performers who have contributed work to the A Year In The Country themed compilations, and also the likes of electronic music pioneers Emerald Web, Delia Derbyshire and the aforementioned Broadcast, who were the cover stars of issue 32.

All of which brings me back to Paul Weller’s In Another Room EP. It’s a fascinating record, equally resolutely avant-garde, melodic and accessible.

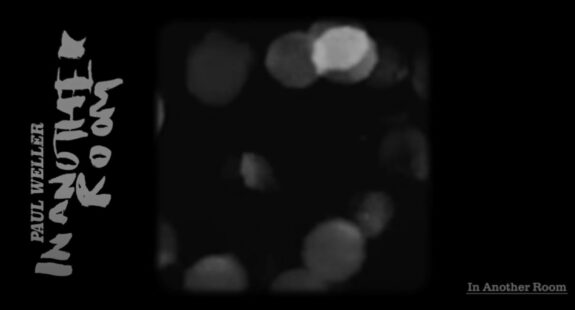

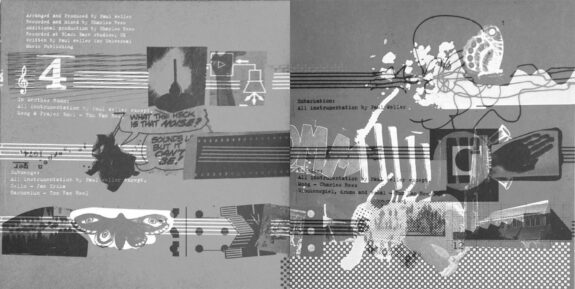

The EP contains four tracks called “In Another Room”, “Submerge”, “Embarkation and “Rejoice”, which were created by Paul Weller and his long-time engineer Charles Rees from a fragmented musique concrète-esque collage of sounds, a number of which were created from field recordings made by Weller and subsequently manipulated via analogue tape. As the EP’s tracks play a looping, possibly child’s voice appears and reappears and fades away; bucolic church-like bells peel; gnomic chants arrive from out of the ether; somebody begins to play pleasantly and gently melancholic piano; running water burbles away; birds quietly tweet; sounds appear and then suddenly drop away in a jump cut-like manner; at points it is as though a distant radio broadcast is trying to break through; and elsewhere bursts of unidentifiable electronic sound have a Nigel Kneale-ian/Quatermass-like otherworldly menace to them.

The final track “Rejoice” begins with subtly unsettling cosmic seeming sounds before a cheerful and uplifting piano jam oscillates to the fore, like some long lost tape loop that is somehow transmitting from the corner of a sunny attic that everybody had forgotten about, and towards the end of the track conventional vocals are introduced and for a moment it almost becomes like a segment from a more conventional song by Paul Weller. But it is only for a moment and then the song quickly and suddenly oscillates away and the track and EP ends on a very Ghost Box-like archival public information film-sounding sample of a woman’s voice saying “Oh dear.”

Stewart Gardiner wrote about the EP at his Concrete Islands website and captured its essence rather well:

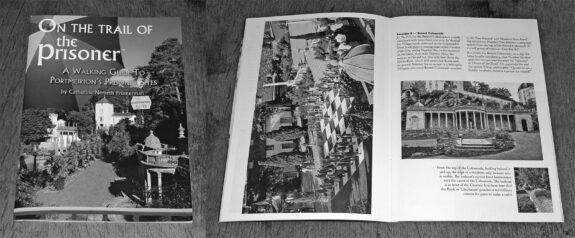

“[In Another Room] contains a plethora of inviting avant-garde ideas that don’t trip over themselves into self-indulgence. It’s The Prisoner via [The Beatles’ sound collage track] ‘Revolution 9’ whilst maintaining easy restraint. If that sounds contradictory then so be it, for this is a 7″ of delightful contradictions… The title track is the sonic equivalent of a door wedged open but a crack, allowing snippets of sounds to be overhead from the universe beyond. Magic is taking place inside or else the magic of places is seeping out…”

The Beatles reference in the above review intertwines with Ghost Box’s co-founder Jim Jupp being quoted in a review of In Another Room in the March 2020 issue of Mojo magazine as saying that the EP is “like a late Beatles studio experiment”, and listening to the EP can be like hearing the lost and refound ghosts of such work carried out by The Beatles that evaded view and was left hidden away somewhere pleasantly bucolic but also subtly and quietly unsettling for 50 or so years, with the sounds of the surroundings somehow imbuing themselves onto the tape as time passed by.

That subtle sense of unsettledness is particularly heightened when watching In Another Room’s final track’s accompanying video which has been posted online by Ghost Box (and is presumably created by Julian House, as it contains his distinctive hazily dreamlike faltering transmission, layered collage, jump cut and minimal duotone, tritone etc style and draws from the colour scheme and visual elements of the EP’s artwork). Just before halfway through the track an ominous tone appears and it seems as though the pastoral fever dream landscape depicted on the screen tips over into darker territories and urban drudgery, which are all the more unsettling for their sudden and brief arrival and departure and the way in which why they are unsettling is difficult to quite put your finger on or define. The resulting combination of the audio and visual elements seem both entrancing and deeply unsettling. Brrrr.

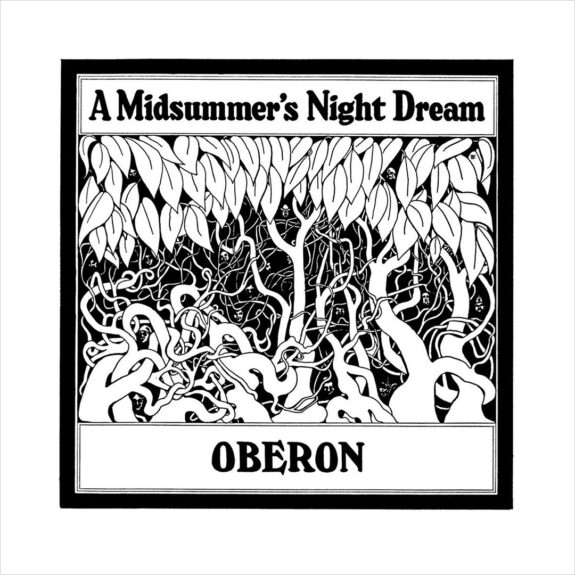

At times In Another Room is not a million miles away from some of the melodic, cut-up experiments and pastoralism of the above mentioned Ghost Box affiliated Broadcast and The Focus Group Investigate Witch Cults of the Radio Age album, which as also mentioned previously was the first album of Broadcast’s that Paul Weller heard.

Interconnected with which, In Another Room also brings to mind the more out there sections of Broadcast’s Mother Is The Milky Way EP/mini-album released in 2009, and its use of pastoral field recordings and an accompanying sense of a melodic, avant-garde and otherworldly “milling around the village”. In this sense and its melding of the experimental and accessible, In Another Room could be seen as an exploration of Trish Keenan of Broadcast’s comment that “The avant-garde is no good without popular, and popular is rubbish without avant-garde” and what writer and academic Mark Fisher described as “the circuit between the experimental, the avant-garde and the popular”.

(As a further aside and in relation to Broadcast, listened to now the instrumental track “In Amsterdam” on Paul Weller’s 2010 album Wake Up The Nation can seem like something of a signpost towards his eventual “stepping through the door” and “into the other room” of Ghost Box’s parallel world, as during the track’s brief one minute and 28 seconds audio journey it seems to channel Broadcast via a sunny day out on a seaside pier that only happened in distant dreams.)

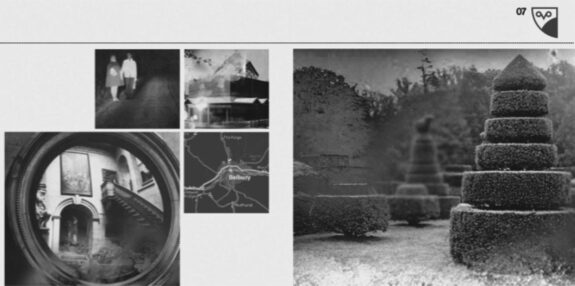

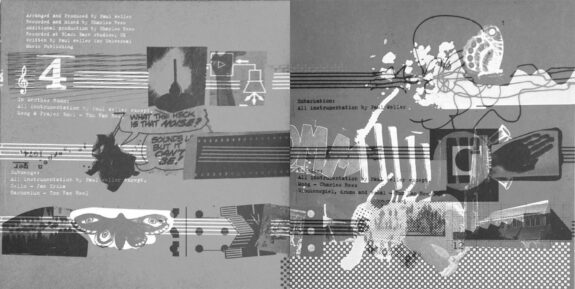

An inherent part of Ghost Box releases and the narratives, atmospheres and moods they conjure and create are the packaging, artwork and design which, including the artwork for In Another Room, are generally created by Julian House. Reflecting the multilayered audio collaging of the EP, the front cover artwork for In Another Room is also multilayered: the topmost layer is a scene of what may be urban decay and that brings to mind the social strife in British society from the later 1970s, and then through a portal-like doorway can be seen shadowed and silhouetted figures, while just behind them are a group of children singing and playing guitar. Off in the distance and seemingly in a field in the middle of nowhere people sit on park benches with their backs to the viewer and further again in the distance another portal-like doorway opens off into… well presumably another room and universe and another doorway and another room and universe and another doorway and…

Each panel of the EP’s gatefold packaging images seems to exist in a space of its own, related to which Jim Jupp said in a January 2020 interview with Bob Fischer on his BBC Radio Tees show, which Fischer transcribed for his The Haunted Generation site that:

“[Julian House’s artwork was intended to capture the] idea of rooms, and doorways, and moving through into other spaces. But what he’s also done… he looked at some graphic scores, which used to be part of the avant-garde, where the musical score was a piece of artwork itself. So you’d often start with a conventional musical stave, but there’d be dynamic paint splatters or shapes on the sheet of music. So on the gatefold of the single, he’s taken that idea and overlayed a collage onto a musical stave.”

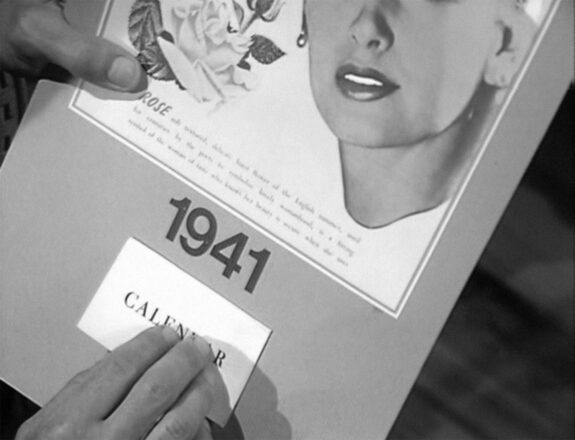

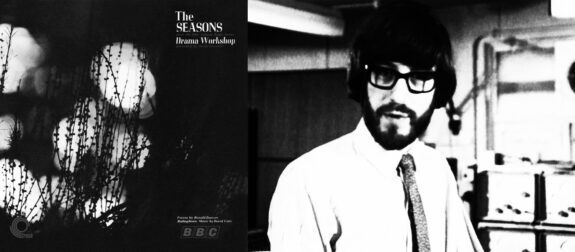

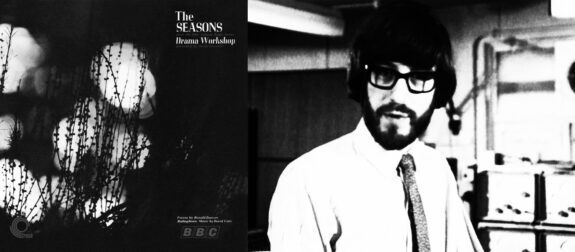

The resulting imagery seems to also capture a sense of possibly being some form of previous era’s more experimental “Music and Movement” educational material, which is an aspect of culture that Ghost Box releases and interconnected hauntological related work at times explores. In this sense it could perhaps be some distant and even more out there relation to David Cain’s The Seasons album:

“Originally issued in 1969, The Seasons has become almost mythical over the last few years. With its mix of unexpected electronics, percussion, tape manipulation and austere poetry, it sounds like no other. The Seasons has also become a major influence on bands such as Broadcast and a key reference in the development of Ghost Box and the whole ‘hauntology’ soundscape. It is seen and heard very much now as an important and lost classic. And after over one year of detective work and rights investigation (which is a lot in this modern world of instant communication), this impressive, strange and wholly unique album is seeing the light of day once again… Originally made as part of the BBC’s Drama Workshop broadcasts, this album was meant for educational purposes. Coming in the later period of what is commonly known and remembered as ‘Music and Movement’ or ‘Movement and Mime Classes’, the album was issued briefly as a teaching aid for the modern thinking 1960s classroom. The idea was to play the album and get the school children to dance, improvise, think and create to the sounds and words.” (Quoted from text which accompanied The Seasons’ 2012 reissue by Trunk Records.)

(As another aside, in an intertwining connections amongst the cultural landscape manner, as commented on by Bob Fischer in the above interview with Jim Jupp, Cathy Berberian created a graphic score for her experimental 1966 sound work Stripsody, while her name inspired Peter Strickland’s 2012 film Berberian Sound Studio, which is also featured in the abovementioned issue of Shindig! that featured Broadcast as the cover stars, and in which a sound engineer’s reality fragments and fractures into a dreamlike world while recording a horror film soundtrack in the cloistered environment of an overseas recording studio. Ghost Box’s Julian House created the titles, poster designs, the film-within-a-film The Equestrian Vortex, graphic design for the tape boxes etc used in the film and also the artwork used for the album release of Broadcast’s soundtrack work for the film.)

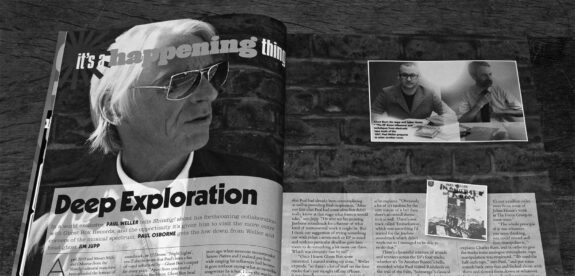

As an almost final note, in issue 97 of Shindig!, there was an article on In Another Room, which was based in part on an interview with Ghost Box’s Jim Jupp and also the time when Jon Mills and Paul Osborne from the magazine’s editorial team visited Paul Weller in his Black Barn studio in Surrey, which is not all that far away from Woking where he was born, to hear a preview of and discuss In Another Room and his collaboration with Ghost Box. The article ends on a humorous note which is quite refreshing in the way that it undermines the sometimes more po-faced aspects of avant-garde and experimental music:

“As our conversation… comes to an end, Shindig! asks if he considered releasing the EP under a pseudonym more in line with previous artists that have graced Ghost Box’s output. ‘No but I’m equally happy to do that as well, I’ll call myself Woking Watermill’s or something,’ jokes Paul. ‘Cycling Club maybe!'”

The vinyl version of In Another Room was issued in a limited run of 1000 copies, the majority of which sold out in around fifteen minutes during the preorder and then on the day of its release, and at the time of writing it has not been repressed and generally fetches a fair few pounds online via Discogs etc, although it is available digitally. Here’s hoping for a physical reissue one day – perhaps on that semi-forgotten format of a CD single? Just a thought, I can imagine it making for a rather fine object as a gatefold CD with a matt/subtly textured reverse board finish.

Links elsewhere:

Related previous posts at A Year In The Country:

- Ghost Box Records – Parallel Worlds, Conjuring Spectral Memories, Magic Old and New and Slipstream Trips to the Panda Pops Disco

- Belbury Poly’s (aka Jim Jupp) Geography and Gateways to Far-Off Neverland Dream Memories

- Belbury Poly’s New Ways Out and strutting your stuff at the Panda Pops disco

- Signals and signposts from and via Mr Julian House

- Signal and signposts from and via Mr Julian House 2: the worlds created by an otherly geometry

- The cuckoo in the nest: sitting down with a cup of cha, a slice of toast, Broadcast, Emerald Web, Ghost Box Records and other fellow Shindig! travellers…

- Broadcast – Recalibration, Constellation and Exploratory Pop

- Broadcast Findings and Anticipating Dreamlike Pastoral Explorations

- Broadcast – Mother Is The Milky Way and gently milling around avant-garde, non-populist pop

- Broadcast Findings and Cultural Constellations

- Broadcast and The Focus Group’s #1: Witch Cults and #2: I See, So I See So

- Mark Fisher’s Ghosts Of My Life and a very particular mourning and melancholia for a future’s past…

- Excalibur – John Boorman’s Creation of an Otherworldly Arthurian Dream

- Katalin Varga, Berberian Sound Studio and The Duke of Burgundy – Arthouse Evolution and Crossing the Thresholds of the Hinterland Worlds of Peter Strickland

- Tales from the Black Meadow, The Book of the Lost and The Equestrian Vortex – The Imagined Spaces of Imaginary Soundtracks

- Your Face Here: peering down into the landfill – a now historical perspective on the stories of The Wicker Man

- The School Is Full Of Noises and gazing into a utopian future…

- Journeying through The Seasons with David Cain (or maybe just July and October)

- The Seasons, Jonny Trunk, the BBC Radiophonic Workshop and Howlround – A Yearning for Library Music, Experiments in Educational Music and Tape Loop Tributes

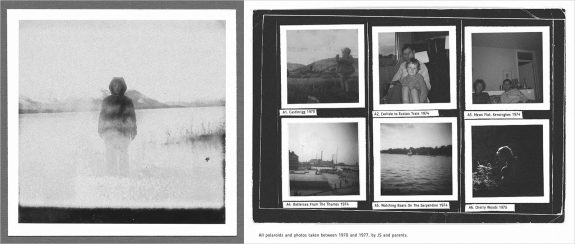

(Above: the city as imagined Bladerunner-esque dreamscape – images from Liam Wong’s TO:KY:OO book.)

(Above: the city as imagined Bladerunner-esque dreamscape – images from Liam Wong’s TO:KY:OO book.)